TL;DR: Scopes only come into play in delegation scenarios, and always limit what an app can do on behalf of a user: a scope cannot allow an application to do more than what the user can do.

Although stretching scopes beyond that usage is possible, it isn’t trivial or natural – contrary to what common naïve narratives would want you to believe.

“.@vibronet on why using OAuth2 scopes in every authorization scenario is not a good idea.”

Tweet This

The Problem

OAuth2 scopes are misunderstood. Developers are victim of the “man with a hammer” syndrome here — scopes are the only primitive defined in OAuth2 that has something to do with authorization, and as a result people use them in every authorization scenario — even the ones for which they weren’t conceived. Just like Newtonian laws are enough to tackle simple problems, the same can be said for those naïve uses of scopes — but as soon as architectures get more complicated, people discover (often painfully) that they need to rethink things in quantum terms to get out of trouble.

It certainly doesn’t help that protocol specs aren’t too prescriptive on this point — a common ailment in OAuth2 — but a deeper read usually helps to clarify things. Circumstantial evidence/spec intent and context on one side, “laws of physics” on the other leave little room for interpretation.

Let me stress: most misunderstandings I discuss here come from legitimate authorization requirements; scopes just happen to be the wrong artifact to carry them. If anything, this points to the need for more prescriptive guidance on the matter (for a primer, see Jared Hanson’s session at Identiverse).

Here’s an extra note to clarify further what I am trying to do here, given that I expect some people will push back hard when their beliefs are challenged.

Like everything that doesn’t really exist in ground reality, the semantic of scopes is entirely in our head: a consensual hallucination where we all agree on the meaning of the term — hence formally you are free to refuse the entire premise of this post and use “scope” to mean whatever you like. The main selection criteria I am using here is, what’s the choice of meaning that will be best conducive of us “thinking good thoughts,” as in taking decisions that will make our solutions work reliably? That’s a terribly relative, very arbitrary thing to establish — one that doesn’t scale linearly. Heuristic for prime numbers is super handy and we could embrace it, but if we need to work beyond a certain number it will stop working: our intended range determines whether the heuristic takes care of our needs, or it’s a dangerous oversimplification that will force us to backtrack and rip out a lot of logic in the process. Same with scopes: we can hold on to simplified views and revel in their apparent neatness, and feel the burn when we go beyond trivial cases and start having to architect serious shit.

Scopes Inception

To all intents and purposes, scopes didn’t really exist before OAuth. The quintessential use case OAuth was devised for is a simple scenario, which has been presented ad nauseam already. LinkedIn asks for your Gmail password so it can use it to log in as you in Gmail, programmatically harvest your contacts (via API/scraping/etc) and spread itself; but knowledge of your Gmail password allows LinkedIn to do far more than that (e.g. sending mails on your behalf, read your messages, etc) and put the secrecy of your credentials at risk.

OAuth shows up, devises a mechanism for LinkedIn to ask Gmail just for the action it requires (access contacts) and nothing else — and makes all this possible without ever sharing with LinkedIn your gmail credentials. Done. Scopes happen to be the primitive that OAuth2 introduced for allowing LinkedIn to request delegated access to your Gmail’s contacts, to the exclusion of everything else. Intent clear and mission accomplished, right?

To me, that would be enough to demonstrate my thesis (scopes only come into play in delegation scenarios, and always limit what an app can do on behalf of a user; they are not meant to grant the application permissions outside of the privileges the delegated user already possesses). However, I know that this scenario alone won’t be enough to convince everyone: a classic objection is “fine, that might have been the original intent, but that doesn’t mean that they can’t be successfully used for more scenarios!.” Fair. Let’s dig deeper and explore more ramifications.

“Scopes only come into play in delegation scenarios, and always limit what an app can do on behalf of a user.”

Tweet This

Scopes as Claims

What I described so far is all about using scopes for asking for permissions. OAuth2 says nothing about scopes being claims in access tokens, given that access tokens (ATs from now on) don’t need to carry claims at all (ATs are shapeless, per OAuth — and per OpenId Connect as well: only id_tokens are defined as JWTs). Nonetheless, the belief that scopes can be used to express authorization beyond delegated scenarios is deeply entrenched in the assumption that scopes do travel in the access token in form of claims. More precisely, the essence of the problem lies the conviction that the presence of a scope claim in an access token invests the bearer with its corresponding permission, and that a resource (API, etc) being invoked with such a token can/should grant the corresponding access level without any further check. It is pretty easy to show that in the general case, that logic wouldn’t work.

To set up our counterfactual, let’s entertain the notion that we are indeed using ATs in a specific format (JWT) carrying scope claims. Here there’s a corollary of the thesis: in the general case, scopes alone in an access token are not enough to carry on authorization decisions. Stealing my own thunder, I’ll tell you the two reasons why that’s the case: 1) the resource visible at the OAuth level isn’t usually the real resource requiring authorization, and 2) the authorization server isn’t omniscient. Let me unpack this through examples: I’ll use Azure AD because the Microsoft Graph is a really good example of this phenomenon.

The OAuth2 Resource Isn’t The Real Resource

Say that I want my web app to call an API to list all the email messages of the currently signed in user. I request an AT for invoking the Microsoft Graph, and I request the scope Mail.Read. Once I get it, I make my web app call me/messages, and get a nice list of emails. All is good. Now, let me make a small change to the call syntax. Instead of me/messages, I’ll call users/guid/messages. Still works, awesome! No surprise there.

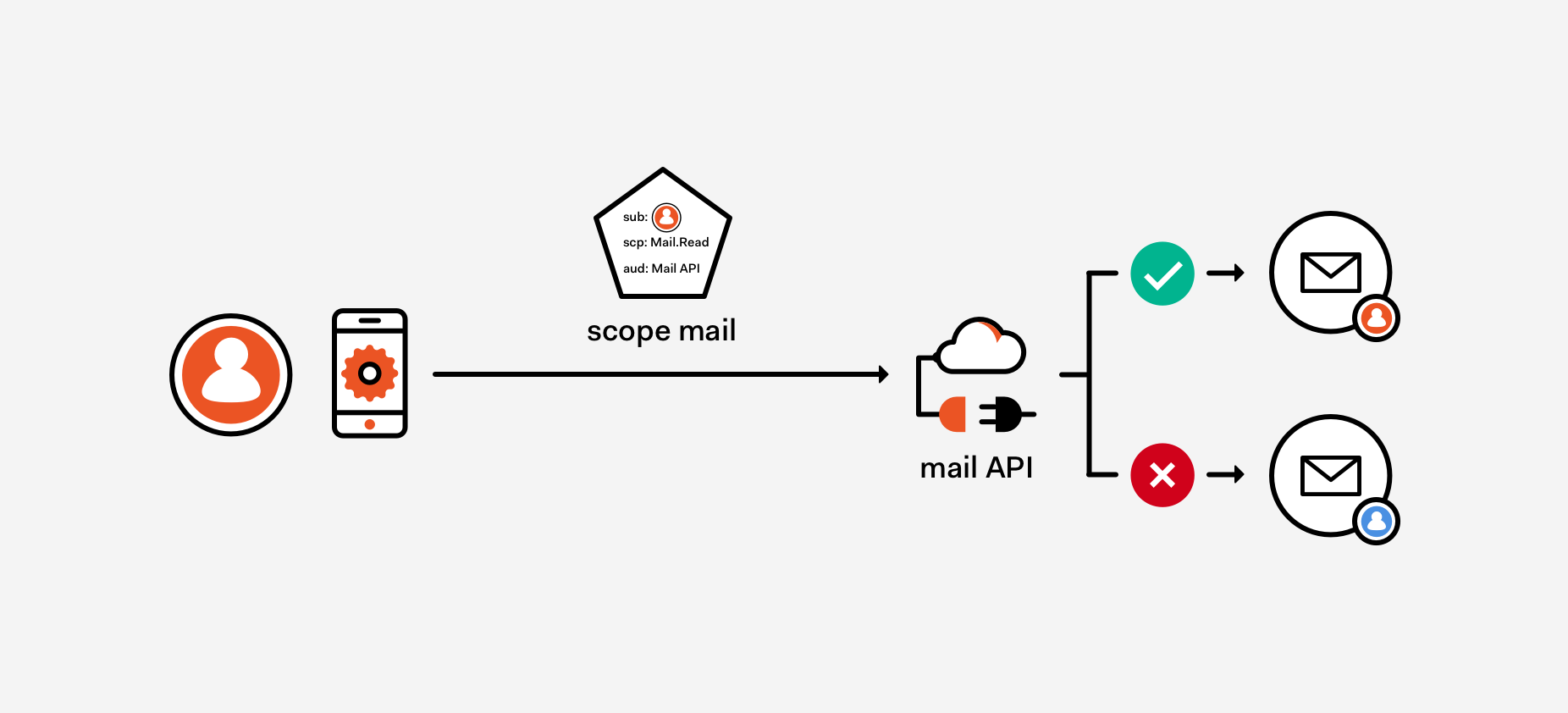

Here’s the twist. Let me repeat that call, this time asking for the messages for another user. I don’t think anyone would be surprised to see the request result in a 400. And yet, my AT carried the Mail.Read scope! The point here is that the scope is only saying to the authorization server (AS) what the app can do on the user A’s behalf, which means that the app can list messages just like user A would, but cannot list messages for user B regardless of the presence Mail.Read scope. In other words, Mail in Mail.Read is a resource type, a family of resources — not a specific instance of inbox. But at access time, the specific inbox being requested does matter. Intuitive, right? If the API behavior would be any different we would be in serious trouble. Figure 1 provides a visual summary of the scenario.

Figure 1: A token carrying the scope Mail.Read indicates that the app can gain delegated access to the user’s mailbox. That scope doesn’t grant to the app privileges that the user doesn’t have: attempts to access another user’s mailbox will fail.

This is an example of 1). The resource we are asking a token for is an API offering a façade for multiple, more granular resources — with their own lifecycle, permissions, privileges and authorization rules. The scope in this scenario is not expressing one of those finer-grained, “ground reality” resources. The true resources in this example are really the inboxes of each user, and that was carried by the REST call rather than the token used to secure it… and the authorization decision emerged from combining the scope Mail.Read (without which we wouldn’t have bothered doing anything else), the identifier of the user (carried through a different claim in the token) and the entity requested (in the URL of the entity, hence in the actual call).

But the solution is simple, then! Let’s just describe those sub-level resources at the OAuth2 level, let’s surface the true resource in the protocol — so that scopes can finally express actual privileges. That is sometimes possible, if the resources you are exposing are ultra-simple, which usually means they don’t exist outside of your API. In term of “thinking good thoughts,” I am still somewhat against that. The fact that you might concoct cases where scopes express authorization directives context-free doesn’t make the aforementioned context-dependent scope uses disappear: if your access control logic now assumes scopes to be of the context-free kind (and more importantly, if you/your developers now understand scopes in those terms), your access checks will be too permissive when you do receive classic delegated scopes as you’ll take the permissions in the incoming scopes as directives, without making the further contextual checks they require (“Sure, he got mail.read — but does he own this inbox?”).

However, that’s not the biggest problem with using scopes to represent granted permissions (as opposed to delegated ones). The biggest challenge derives from the fact that permissions are always resource specific, and that transfers a lot of complexity to the AS and the tokens it issues. Resources can be very numerous, leading to A LOT more token requests than in the general case; they can have heavily decentralized life cycles, which makes it hard for the AS to know enough about assigned permissions (or learn about it in timely fashion) to be able to express that as claims; and permissions on an individual resource can be numerous and/or verbose, leading to unmanageably large tokens.

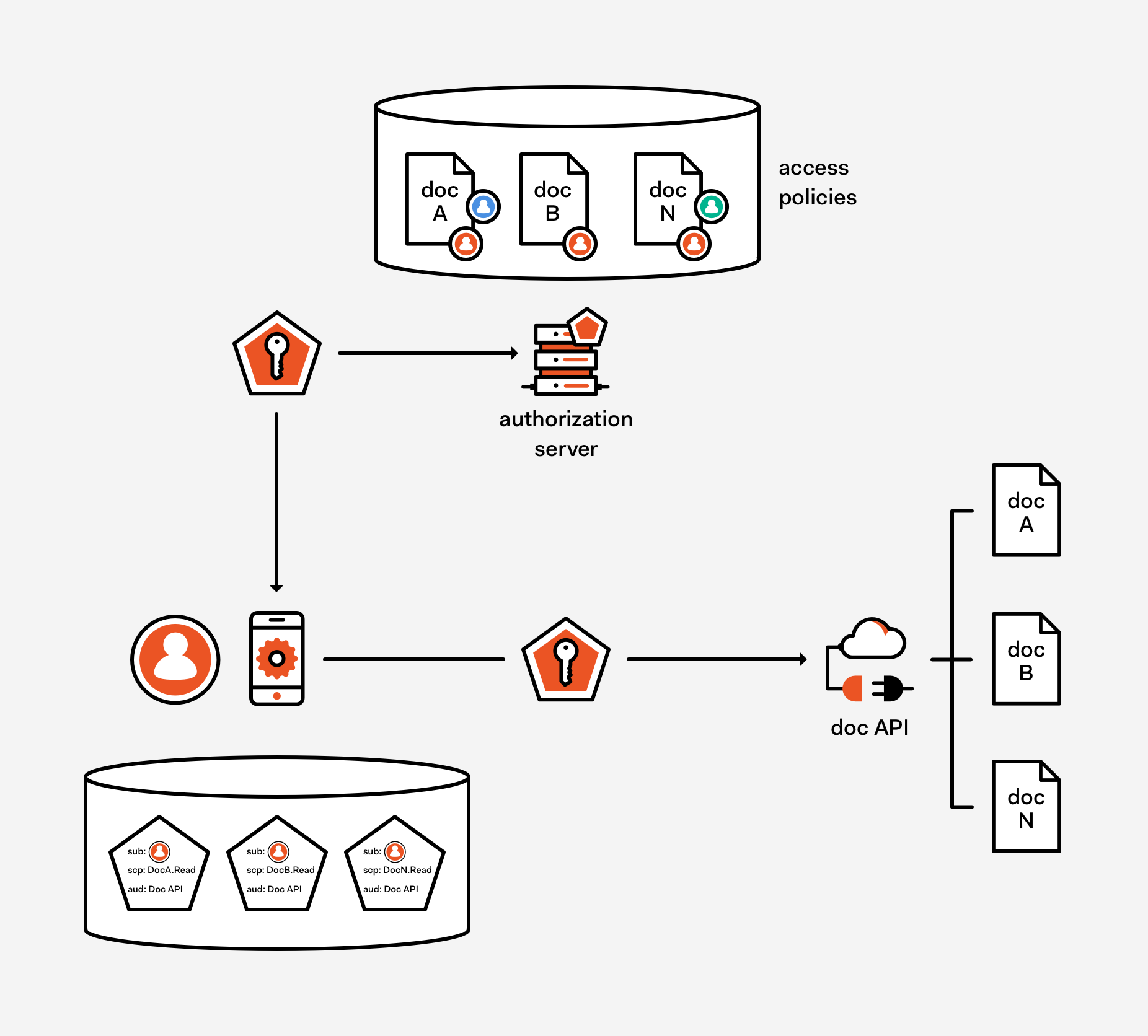

To make things more concrete, think of the case in which the resources being accessed are documents in some repository. According to the naïve view I sketched earlier, we can turn scopes from a delegated hint (which requires the resource to intersect the delegated permission in the scope, with the actual user privileges on lower-level resource being requested to obtain the effective permissions reflected in the access control logic) to an actual assigned privilege (the sheer presence of the scope is all the resource need to grant access, without checking anything elsewhere) just by directly expressing the document itself in our token request, rather than a generic API for accessing documents in the repository. The scenario is on display in Figure 2.

Figure 2: it is possible to surface at the protocol level the actual resources being accessed; it is also possible to relieve the web API from the need to keep track of access policies, relying entirely on the claims included with the incoming token. However the price to pay is an omniscient AS and more tokens than the approach shown in Figure 1 required.

Note: The mechanism we use for expressing that in the request to the AS doesn’t matter for the purpose of this discussion. for example, we can add a prefix to the scope string to point to the exact document we want, followed by the action we request (e.g.

The approach hinges on the assumption that the AS knows every resource, and knows all the policies governing who has access to what — and in what terms. This is represented by the access policies store in Figure 2. Armed with that knowledge, the AS can immediately evaluate whether the requestor has indeed the privileges corresponding to the permissions being requested and A) refuse to issue a token if the requirement aren’t met or B) issue a token containing a statement that access policies have been evaluated and the user should be allowed to perform the requested operation. In the case of B), any resource trusting the AS (and any resources whom delegated its full access management policies to the AS, a function NOT enshrined in either OIDC or OAuth) would simply follow the authorization directive contained in the token.

Now, let’s ignore for a moment that there’s no reason for such a statement to travel in a scope claim — one can pick ANY claim type without the need to overload an entity meant for a different scenario and make scopes consuming logic more complicated. Regardless of what claim is used, requesting a different token for each different document would create a very large increase in traffic. It’s not uncommon to see repositories with millions of documents, even in mid-sized businesses. Imagine the traffic generated by a simple thumbnail generator for a folder, multiplied for all the concurrent users across all the apps portfolio of the company, and all the ripples downstream to that (e.g. increase in size for token caches for offline use, increased lookup time to use those caches, etc., etc.).

Then there’s the matter of how many privileges you’d want to transmit in a token. Although having a client request different tokens for read and write operations is possible, that would exacerbate the tokens explosion challenge; but batching all the privileges a user has for a given document would be problematic as well, as the token itself could become very large. Expressing claims by reference is always possible, but having to make an API call for evaluating a claim would somewhat defeat the purpose of having scopes as a simple, immediately consumable source of truth for all things authorization.

The Authorization Server Isn’t (Usually) Omniscient

But finally, the biggest problem of all is that having to keep the AS in the loop whenever documents are created, destroyed or assigned in different capacity to users is a daunting task — one that isn’t done even in much simpler settings than cloud and distributed systems based on public networks.

Think of how access to files is regulated in Unix or Windows: the domain controller doesn’t keep track of every file’s ACL — every file has a local policy, which is evaluated at access time rather than at ticket generation time. If OSes have to rely on resource side policies, despite all the simplifying conditions they enjoy (homogeneous resource types; constant line of sight with the domain controller; reliable network operations; etc), how could we expect this to be mainstream in the far more challenging public cloud scenario?

Now, technically all of this can be done. But it requires A LOT of work, very precise assumptions about the resources types and lifecycle, a very flexible AS, and so on — far from the naïve assumption that given that the ‘A’ in “AS” stands for “authorization”, all authorization logic can be centralized in the AS and all authorization decisions can be expressed as scopes values.

In Summary

In the general case, scopes are used to express what an application can do on behalf of a given user — and that is always a subset of what the user can do in the first place. In other words, scopes are used for handling delegation scenarios. Resources are responsible to combine the incoming scopes and the actual user privileges to calculate the call’s effective permissions and make access control decisions accordingly.

Again in the general case, overloading scopes to represent actual privileges assigned to the app (as opposed to the delegated permissions mentioned above) is problematic — as it requires the AS to have specialized authorization knowledge at a granularity that is often not practical to achieve and maintain; even in the case in which that’s viable, the increase in traffic and token size might still render the approach unfeasible.

That is not to say that the AS should not make authorization decisions; if the AS happens to have access to data and logic that make it possible to take authorization evaluations at token issuance time, those can certainly be reflected in the decision of withholding issuance, or in the content of the issued token — but there’s no reason for the latter to be expressed in scopes claims, and doing so can in fact contribute to keep alive the urban legend that made me spend about half of a long flight writing this also long post.

About the author

Vittorio Bertocci

Principal Architect