Anti-spam filters have come a really long way. While junk mail still makes up 86% of the world's internet traffic—400 billion messages a day—it doesn't seem to wind up in our inboxes very often, if ever. But it's because we're accustomed to feeling so safe in our email that we're actually more vulnerable than ever to modern phishing and spoofing techniques.

But there's a new generation of scammers out there. In an attempt to get past all your filters and protocols, they're going artisanal.

These criminals are crafting higher quality spam messages and picking smaller groups of people to target. They're not pretending to be Nigerian princes: they're pretending to be from Apple, or from Google, or from the company where you work. And it's working—every year, these “artisanal spammers” steal billions of dollars from small-to-medium size businesses.

“Cyber criminals are crafting higher quality spam messages and picking smaller groups of people to target”

Tweet This

Maybe you think you'd never fall for it. But it's not about you: it's about everyone at your company. All it takes is one clever scammer and one unsuspecting person's momentary lapse for your company to potentially lose millions. To understand why artisanal spam is so dangerous and so effective, we first have to return to one of the most memorable internet scams of all time.

Why The “Nigerian Prince” Scam Was So Genius

We all remember the Nigerian prince email scam. It usually went something like this: “Dear beloved friend... due to a [tragic financial collapse/death in the royal family]... I must [come to America/hide my fortune]... Please reply if you can help.” For many of us, it was our first ridiculous introduction to phishing: when someone masquerades as a trustworthy source to try and get to your sensitive personal information.

Microsoft researcher Cormac Herley, who wrote the seminal paper on this scam, argued that this scam relied on being seen as inept, even comical. After all, only those gullible enough to respond to a “far-fetched tale of West African riches” would be gullible enough to then give up their sensitive personal information when asked for it.

Con-men as far back as the 15th century have this trick, a modified version of the Spanish Prisoner scam. But there's a key difference: the “Nigerian scammers” never focused their efforts on convincing one person to become a victim. Instead, they sent millions of intentionally unconvincing emails in order to self-select for the best possible victim.

It was an ingenious way to leverage the power of the early Internet. But these kinds of scams have lost almost all their effectiveness, and there are two basic reasons why:

- Legislation like CAN-SPAM set out tough penalties for spammers and mandated easy to spot opt-out buttons, while advanced anti-spam algorithms keep 99% of junk mail out of our inboxes anyway.

- People are so accustomed to these stories—Nigerian princes, shady prescription drugs and fake “New Message” notifications—that even if they do get into your inbox, they're not convincing.

These two factors are essential to understanding why “artisanal” spam poses such a threat.

Spam Always Finds A Way

Last October, a group of hackers sent out an phishing email to French iTunes users. The operation was a massive success by modern standards: almost all of the emails reached people's inboxes and the spammers were able to run the operation for eight full hours before they were stopped.

A similar attack around the same time specifically targeted Italian PayPal users. Those also came from a small data-hosting company, a French one that had never been on any worldwide blacklist, and they were similarly effective.

There are a variety of reasons why these artisanal attacks are so effective. Let's go through them one by one.

They narrow their scope

The hackers that went after France's iTunes users didn't try to send messages to all of France's iTunes users, which would be millions of people. Nor did they send messages just to a few high-profile members—a technique known as spear phishing—whose account information would be inordinately valuable.

They sent it to 5,000 people. And it worked—the vast majority of these messages were delivered.

The Italian PayPal scammers targeted even less, picking just 169 people. Conventional spam filters tag floods of identical or near-identical messages as spam, so the fewer recipients a spammer chooses, the higher the likelihood their attack will succeed.

They send through obscure hosts

The big email hosts that are used to dealing with spammers have all implemented authentication protocols like:

- DKIM, which lets organizations take responsibility for the emails they send.

- SPF, which validates emails by cross-referencing the originating domain with a universal whitelist.

- And DMARC, which gives users of DKIM and SPF the power to talk to other companies about what mail is/is not getting through and make recommendations.

These let them intercept spam before it's ever sent. But artisanal spam flew under the radar of all these protocols because the hosting companies they used were small and inexperienced.

Not only do these protocols require investments of time to set up and maintain, they can sometimes block totally legitimate mail from going through. That means dedicated spammers can usually find a host that will send their messages without flagging them.

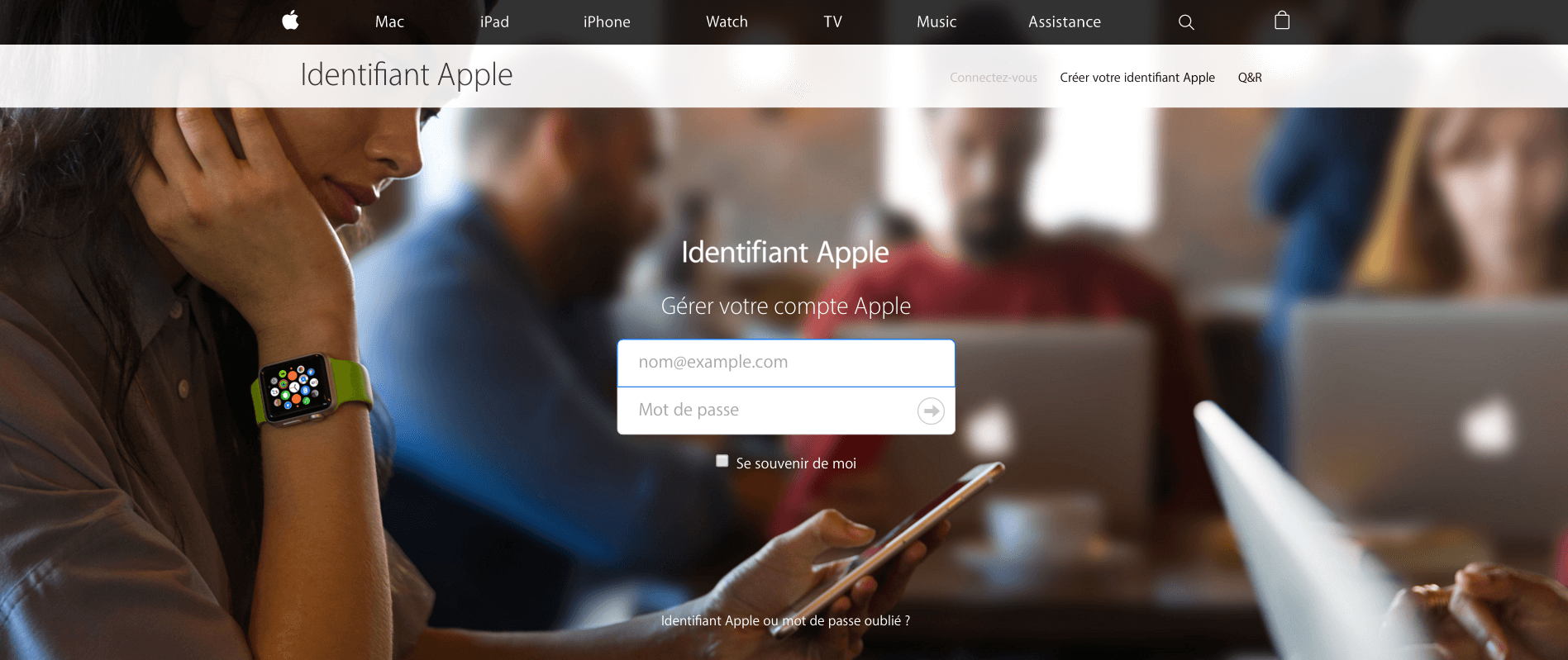

They spoofed with picture-perfect accuracy

The emails that the French iTunes spammers sent had spoofed headers, so they appeared to come directly from Apple. In the body of the email, there was a link to a login page that looked eerily like the one on Apple's legitimate website:

If you're thinking “Well, that's stupid, I'd never fall for that,” give it a bit more thought.

For instance, I bet you think that the average Twitter engineer is a pretty smart person. Yet when Twitter sends its new employees phishing emails with spoofed headers to test their security acumen, do they mark it as spam or report it to IT? No. They fall for it all the time.

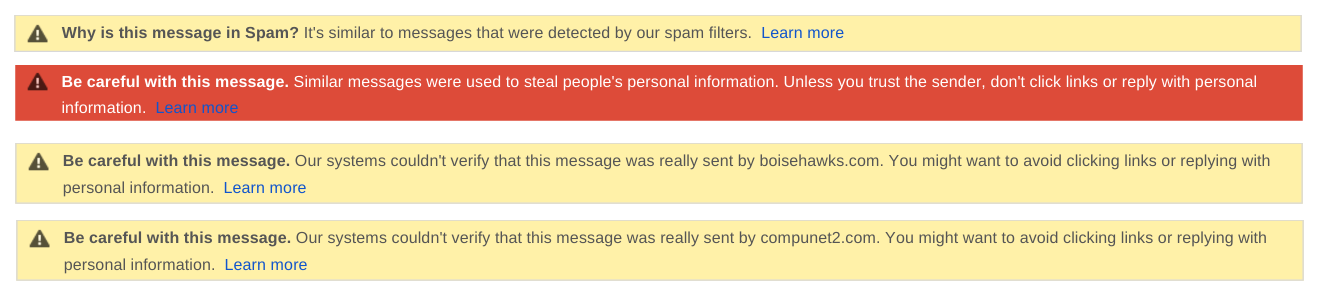

Spammers have figured out that crafting high-quality spam and sending it to a small segment of users is their best bet for phishing login information and gaining access to people's accounts. And protocols like DMARC are useful, but they lose effectiveness if even a single company doesn't apply them. A false sense of security pervades the way we think about email, and no protocol can fix that.

We trust our inboxes too much

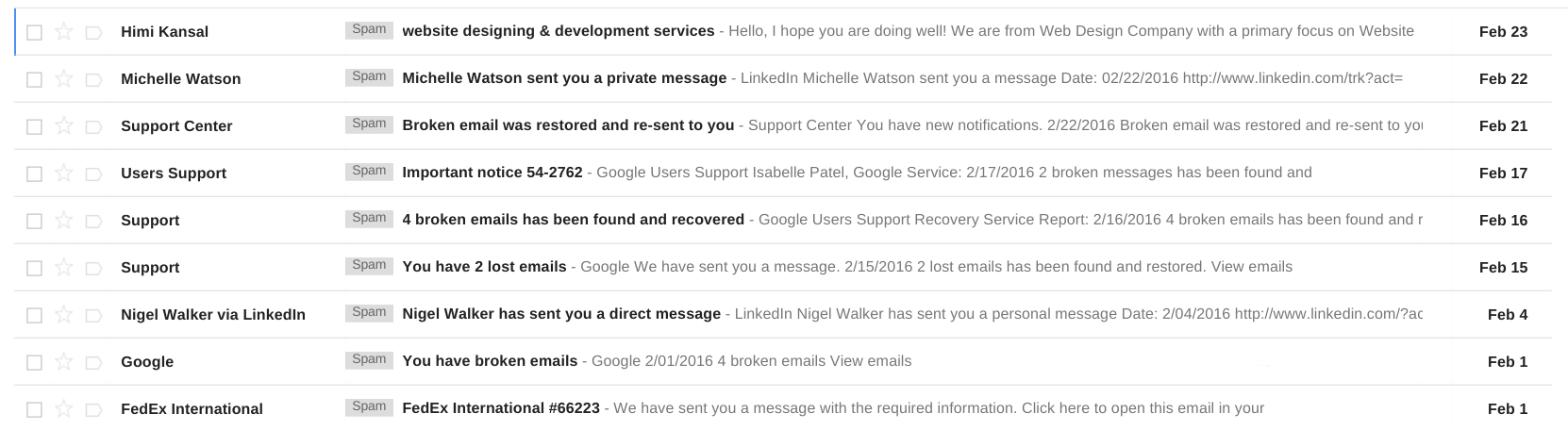

Opening your spam folder kind of feels like going back in time. It's hard to believe that anyone ever fell for these tricks: it's even harder to believe they do today. But this is the wrong attitude to have about spam.

Because most of us have very good anti-spam filters, we've grown extremely accustomed to having clean inboxes:

An overflow of calendar invites and email newsletters, maybe, but scams and viruses? No chance.

That means that when our safeguards fail—when spammers are able to use small batches and little-known hosts to bypass anti-spam filters—we put ourselves and the companies we work for at incredible risk.

Scammers Infiltrate Organizations From Above

According to the FBI, well over $1.5 billion have been stolen from companies in email spoofing scams just over the last few years. Because the scams are so often aimed at executive leadership, they've become known collectively as “CEO fraud.” But they don't usually target the C-suite directly—they infiltrate through trusted employees.

In one case, an accountant received an email from the CEO of her company. It requested funds to be transfered for a time-sensitive acqusition—$737,000 by the end of the day. She approved it.

The next day, the CEO called her about an unrelated matter. During the conversation, she happened to mention the wire transfer from the day before, at which point the CEO exclaimed that he knew nothing about this purported transfer of funds. It turns out the CEO's email password had been stolen, and his account had been used by a scammer to send the transfer request to the accountant.

And this theft probably hadn't happened anytime recently. Artisanal spammers don't just find your username and password and flagrantly send out a bunch of requests for money.

They sit on it. They comb through all of your correspondence and learn how you write and how you think, the vocabulary you use to talk to your colleagues. They ingest as much information as they can, and when they feel ready to strike, they do. And attacks like this are very common:

- Ubiquiti Networks, a networking firm in San Jose, lost $46.7 million when a scammer was able to successfully impersonate both an employee and a outside financial entity.

- Scoular Co., an employee-owned commodities trader in Omaha, lost $17.2 million when an accountant wired the money in installments to China—because he received an email “from his boss” asking him to.

Inadequate authentication turns you into prey

The scammers that commit this kind of fraud rely on businesses having inadequate authentication in place.

If those email accounts had been protected by something more than a password, then virtually none of these scams would have succeeded. Those businesses wouldn't have had to get into complex legal negotiations with the Chinese banks where their money was funnelled, and their reputations for security would have been spared.

If you want to get access to something (your email, your Seamless account, your company intranet) and you're only asked for digital credentials, you're susceptible to an attack.

Knowledge, Possession, Inherence: How To Authenticate

There are three basic types of authentication. You can be identified based on knowledge (what you know), inherence (what you are), and possession (what you have).

1— The Knowledge Factor The password is the classic knowledge factor. It's as old as “open sesame” and Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves. But “secret questions” are also knowledge factors, and not particularly good ones.

If your Gmail account asks “What's your mother's maiden name?” to authenticate your identity, and you're a public figure or head of a company, it's not going to take long for a semi-dedicated scammer to figure that out through public records.

2—The Inherence Factor Access to Mjolnir, Thor's mythical hammer, is controlled by an inherence factor. Thor himself can wield Mjolnir with ease: he can throw it into the air, summon it to return, use it to manipulate the weather. But no one else can lift it, not even Doctor Doom, because it's tied into Thor's unique identity.

That's great security policy. The same principle is at play in modes of biometric or GPS authentication: only your retina, fingerprint, or precise geographical location will grant access.

3—The Possession Factor The last factor, possession, is the easiest and quickest (after knowledge) to implement. It relies on you physically having something—a smartphone, memory card, or badge—that wouldn't fall into a scammer's hands through digital means.

If you're currently only using a single factor to authenticate, we recommend—at minimum—implementing two-factor authentication.

It can be annoying at first having every log in and sensitive transaction verified twice, but this alone will virtually eliminate the possibility of a phishing or spoofing scam affecting your company.

The Practical Way To Protect Yourself And Your Company of Artisanal Spam

DMARC, DKIM, and SPF are great. The spam filters that Google has developed to protect Gmail are great. But they're not perfect—spam filters fail, and protocols are vulnerable as long as they're not universally adopted. Getting every company in the world on the same page is a Sisyphean task, so let's get practical.

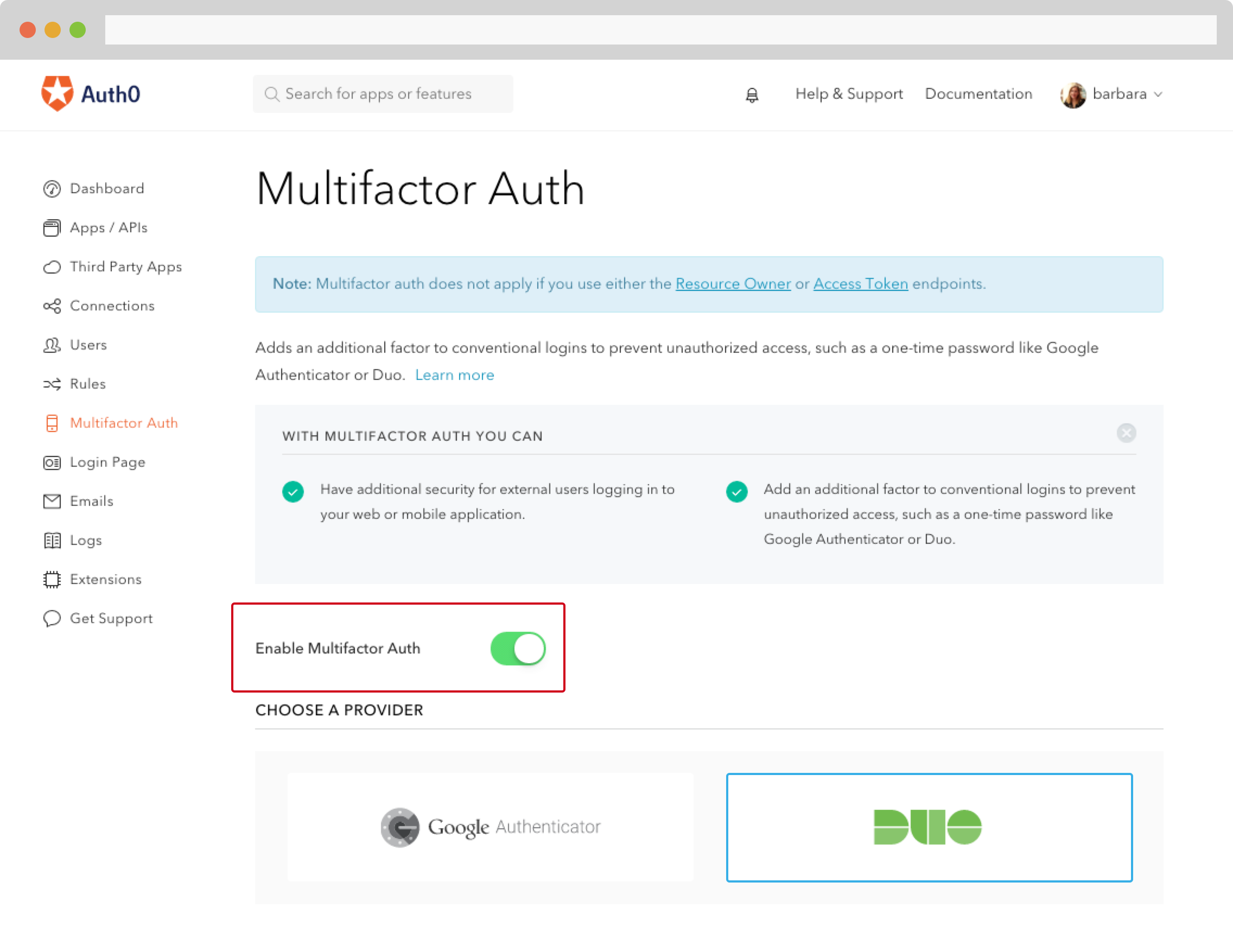

Implementing multi-factor authentication on your business email (some combo of knowledge, inherence and possession) is really the only way to be safe.

And setting up multi-factor authentication is easy with Auth0. Whether you want to enable it by default, trigger it only under abnormal or specific conditions, or involve custom hardware, you're covered.

Support for Google Authenticator and Duo Security are built in, so enabling MFA via those is as simple as flipping a switch:

Implementing MFA exclusively in special situations—first login from an unfamiliar device, for instance—is only slightly more complex. For the full how-to, check our documentation.

However you choose to do it, you have several options as far as what your second factor (after your password) will be. Some popular ones:

- Time-based One-Time Password, or TOTP: this generates a single-use password using the current time along with a secret, shared key. These only work for 30-60 seconds.

- SMS verification: when a user tries to login, an SMS is sent to their mobile phone. If they don't have it, they don't get in.

- Hardware: companies like Yubikey make USB dongles or other accessories that maintain special password-generating keys.

Conclusion

You can't completely protect your company from attacks by artisanal spammers, but you can go “upstream” and institute a higher level of protection where you really need it the most—on your identity. Multi-factor authentication is the best way to do that. Implemented correctly, it can make the chances of an attack like that succeeding virtually zero.

About the author

Martin Gontovnikas

Former SVP of Marketing and Growth at Auth0 (Auth0 Alumni)

Gonto’s analytical thinking is a huge driver of his data-driven approach to marketing strategy and experimental design. He is based in the Bay area, and in his spare time, can be found eating gourmet food at the best new restaurants, visiting every local brewery he can find, or traveling the globe in search of new experiences.View profile