Phishing is a type of social engineering attack, generally delivered by email, with the intent of stealing the target’s login credentials and other sensitive data, such as credit card information or ID scans, to steal their identity.

A noteworthy trait of phishing is the element of surprise: these emails arrive when the victim doesn’t expect them. Criminals can time emails so victims will receive them when distracted by something else, such as work. It’s impossible to be focused on being productive and attentive to suspicious emails all the time, and fraudsters know it.

The emails are crafted in such a way to avoid snapping the victim out of autopilot and comply with the fraudsters’ requests. They may impersonate someone, often entities or colleagues trusted by the victim, and exploit biases we all have as humans to increase the likelihood of compliance.

Statistics

In my last article, I wrote about how U2F security keys work and how they secure people against phishing. Now, why do we need U2F keys to prevent phishing attacks, to begin with? Do people still fall for the Nigerian prince scam?

According to the 2020 edition of the FBI Annual Internet Crime Report, phishing attacks were by far the most common attack, representing 32.35% of all cyberattacks last year, with 241,342 occurrences registered. This figure increased more than tenfold in the last five years, up from 19,465 in 2015.

Despite improvements made to email filters throughout the years — Google filters out 100 million spam emails per day for Gmail users — phishing attacks are still popular for two reasons:

- They don’t require complex expertise to pull off: crafting convincing emails and creating fake websites, and

- They are easily scalable, which ends up being much more time-efficient than, for example, trying to break into a server.

It’s frequently said that humans are the weak link in security, and it’s no different from phishing. For example, fraudsters capitalized with great success on people’s fear during last year with the COVID-19 pandemic.

The 0.1% of phishing emails that pass through email filters is still enough to be extremely profitable for scammers, and that they should be doing more of it, which means users should be even more careful in the upcoming years.

How Phishing Attacks Work

The majority of phishing attacks are delivered via email. The attacker most likely gets their hand on a list of breached emails and sends phishing emails in bulk, expecting to trick at least a fraction of the list.

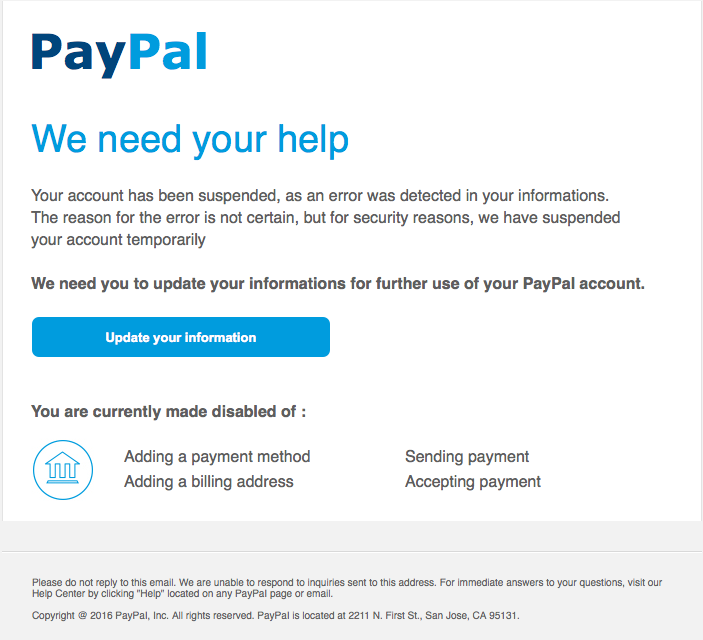

The sender often tries to masquerade as a reputable entity, such as the person’s utility company (in the case of an individual) or a supplier (in the case of a business).

The goal of the email is to trick the user into replying or, more commonly, to click on a link that will lead them to a fake website that looks like the legitimate website they’re portraying. The user then tries to login into the fake website, thinking it’s the real one, and the attacker can steal their password.

Depending on how far the attacker went with the fake website, he might also grab additional information necessary for identity theft. For example, he may build a dashboard resembling that of the legitimate website and ask for the person’s credit card information, Social Security Number, address, etc., to use in future attacks.

Other than the generic phishing campaigns, there are other kinds of phishing attacks that you should also be aware of.

Spear-phishing

Most phishing attacks happen due to the law of averages — if you have a big enough list, you are bound to hit some exactly when they are distracted with colleagues, or under pressure to meet some deadline, etc. Because of this, the attackers often don’t spend a lot of time personalizing the emails.

However, sometimes attackers will specifically target individuals in which it pays to spend time personalizing the message. Attacks aimed at one person are known as spear phishing, concerning the activity of fishing with a spear instead of fishing with a wider net.

Whaling

A step beyond spear-phishing, whaling is a special type of spear-phishing attack where the fraudster targets high-profile individuals, such as the CEO in the private sector or high-ranking government officials in the public sector.

Whaling attacks will often try to get a subordinate of the victim to perform an action; the FBI report shows that criminals will often try to gain control of the CFO or CEO and request wires to fraudulent accounts.

Spoofing vs. Phishing

Spoofing is a kind of attack where the attacker pretends to be someone else to manipulate the victim. Most phishing attacks use spoofing as a social engineering tool, but not all spoofing attacks are phishing.

For example, spoofing attacks are also used as attack vectors for ransomware attacks. In a typical ransomware attack, the victim receives an email with a compromised attachment containing malware that, upon execution, encrypts their computer files. The bad actor then requests a ransom to provide the victim’s files back.

Phishing Attacks Typical Target

According to the same FBI report, the most frequent target of fraudsters is people over 60 years old, totaling 105,301 attacks in 2020. However, the most profitable target is adults between 50 and 59 years old, raking up about $9,900 per attack, followed by adults between 40 and 49 years old.

The reason for this may be justified by the groups’ buying power, but surprisingly, attacks targeting people under 20 years old were more profitable than those targeting those between 20 and 29, the least profitable group to attack.

In terms of victim loss, the report found that the most frequent type of attack was to businesses that generally work with suppliers and partners abroad and are used to making large money transfers. This is three times as much as profitable as the second type of attack: those pretending to be close family or friends requesting money. The third most profitable were discussing investments, where the fraudster convinces a victim to invest in fake opportunities.

Why Phishing Works

Despite those who are older than 30 years old being more vulnerable to phishing attacks, it’s important to note that phishing works regardless of age.

See, for example, the account of this person on Reddit, who describes himself as “paranoid,” has a different password for each website and MFA turned on when applicable, and still got phished.

This happens because the emails are crafted to tap into the victim’s unconscious biases despite the level of tech literacy, according to Daniela Oliveira, cybersecurity expert and associate professor at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

Cognitive biases are “shortcuts” the brain takes to save energy. They are designed to stop us from spending too much energy deciding between the options available (say, “threat” and “not a threat”) each time we run into an unfamiliar situation over and over again.

Instead, the brain looks for patterns to make the decision-making process faster, but in doing so, introduces a few blind spots that can be exploited by an attentive fraudster.

Take, for instance, the truth bias. Our default behavior is to believe people are telling the truth unless we have very good evidence to think otherwise. When you stop people on the street to ask for directions, you assume they are telling the truth.

Only when you’re in a hostile or unknown environment (e.g., in a foreign country), you have your defenses up a little bit more, and you start looking for signs that someone might be deceiving you.

If humans operated under the assumption that everyone else was lying, it would be impossible to be productive — what if this attachment that John sent me is malicious? — not to mention tiring... and in caveman times, lethal.

Criminals and fraudsters exploit this to their advantage. They carefully consider the time, context, and wording when crafting messages to induce their victims to perform the desired action.

While researchers have been aware of the psychological effects of cognitive biases for decades, none of them considered their effect behind screens — it wasn’t until recently that new research emerged, and we gained some new insight into how phishing attacks trick us.

Phishing Attack Examples

Professor Oliveira teamed up with another University of Florida researcher, psychologist Natalie Ebner, to study how people would react to a phishing campaign using different approaches.

They built on top of works from Daniel Kahneman (Thinking, Fast and Slow) and Robert Cialdini (Influence) and identified biases that are more heavily used in phishing campaigns when compared to others: commitment, liking, scarcity, authority, and reciprocity. Social proof and contrast were also found to be relevant, but they are frequently paired with one of the other main five, so they were left off of this piece.

Commitment

Commitment is the concept of completing an action you already started. You are much more likely to hop onto the treadmill if you’re already put on your gym clothes and drove to the gym — plus, you also already paid for your membership... might as well use it (that’s yet another commitment).

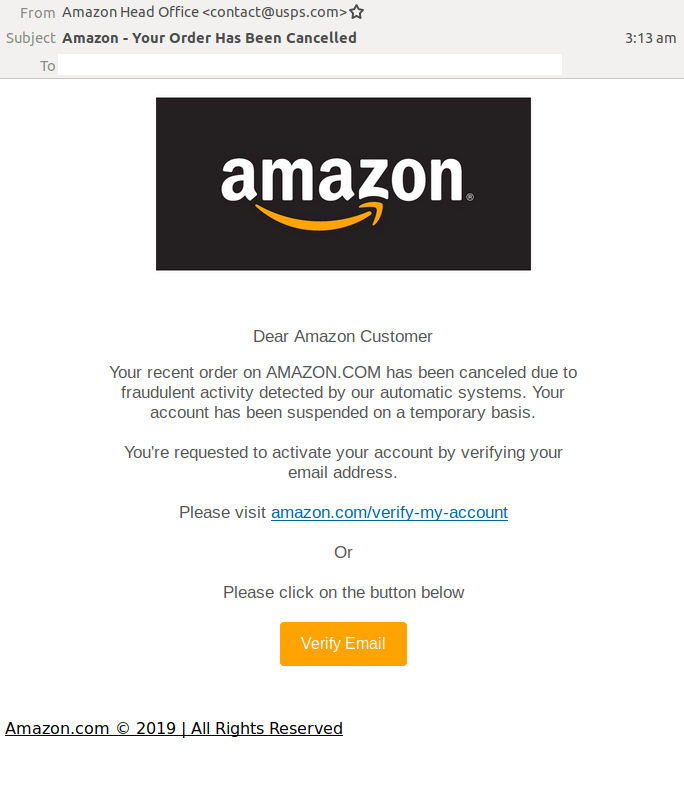

Criminals try to use the same principle to trick you into “finishing” an action that you supposedly already started. They can pretend to be Facebook and ask you to update your profile (you’ve already created the account) or Amazon and ask you to confirm your order (you already bought the product).

Liking

Liking is an extension of our truth bias. It’s trust in people or things you’ve seen or interacted with before.

It doesn’t need to be an extensive interaction, either. A widely recognizable brand will probably appeal to a large portion of the scammer’s targets; in spear-phishing (i.e., targeted) attacks, users make it easy for criminals by “liking” brands they like on social media.

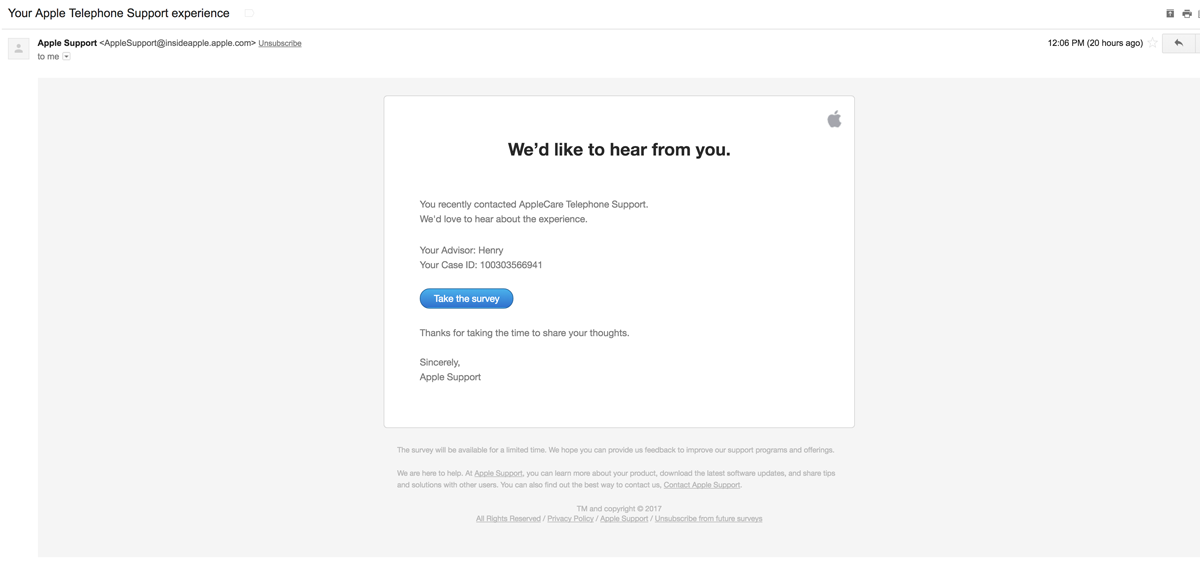

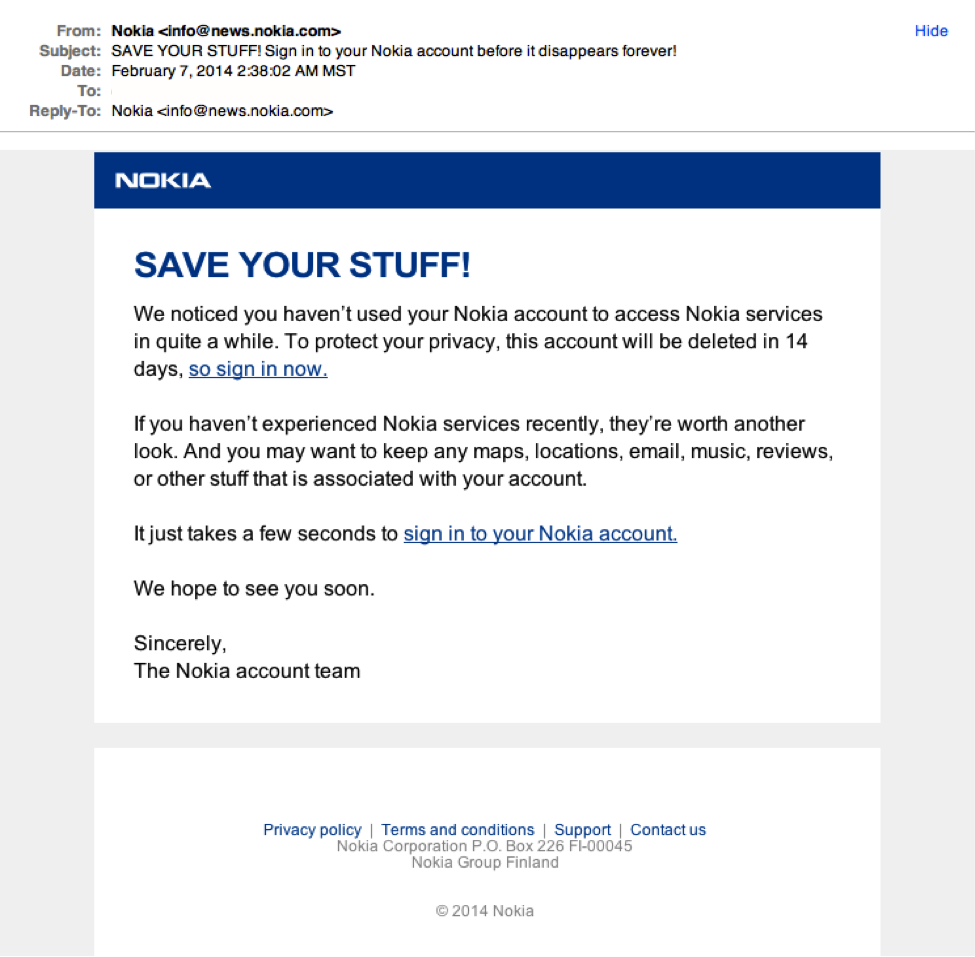

These emails appear to come from a sender which the victim will like or at least be familiar with. They often ask for help by filling out surveys or notify the victim they are the winners of some prize.

Scarcity

Scarcity is a short and specific time frame to complete an action. We see scarcity everywhere, from Black Friday deals to product launches, and we do because it works.

See, our brain is really sensitive to scarcity — 100,000 years ago, we didn’t know when we’d come across water or food again, so our brain is wired to act quickly while resources are available.

Authority

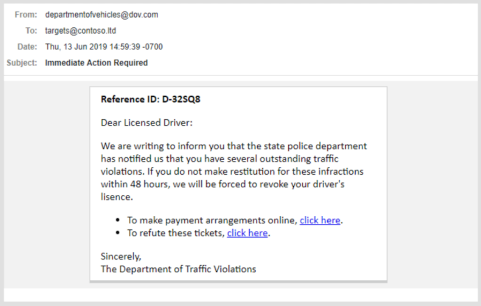

An authority figure is mandating an action, with consequences for failing to comply.

Most people will try to conform to the rules we agreed on as a society and will obey the law. That’s why people will be much more likely to open an email from the IRS or a law firm.

An adversary will try to impersonate government entities when doing a broad phishing campaign and perhaps the victim’s supervisor in a targeted campaign. He knows the victim is less likely to hesitate with demands that appear to come from the boss.

Reciprocation

If someone invites you for their birthday, you feel socially pressured to invite that person to your birthday. That’s reciprocity. Scammers will try to “guilt” you into doing something after they’ve done a favor to you. Under such circumstances, people are much more likely to comply with a request.

Phishing Warning Signs

The researchers also found that people are much more likely to engage with these emails in what Kahneman calls “System 1,” or the fast and emotional decision-making system.

We use System 1 when deciding where to sit in a waiting room or when choosing which snacks to get in the cafeteria. System 2 is for slow and deliberate decisions: where to live or which car to buy.

They found that people who went through training to learn how to identify phishing emails eventually end up clicking again on malicious links because they were operating under System 1 when doing so.

However, if they stopped for a moment and analyzed the emails with the slow, deliberative part of their brain, they become way less likely to fall for scams. Below are some things that phishing emails have in common (other than the underlying tone) that should trigger you to switch to System 2.

Grammar Mistakes

Phishing emails frequently have grammar mistakes or wording that feels “off.” The reason why this is the case is uncertain, but a plausible explanation is that most people sending phishing emails are not English native speakers.

And as mentioned before, phishing is a numbers game. The attackers are trying to cast the widest net possible, hoping that a fraction of a percent of those who receive the email will be distracted enough to open it. Out of the millions of people that receive phishing emails, some will invariably not notice them.

Another possible explanation is that the adversaries are targeting people that are more likely to not pay attention to details in case they need to interact personally with the victim (e.g., call them to request the 2FA codes).

By clicking on phishing links even when the email contains a series of typos may signal to the fraudster that they are more prone to being scammed.

Shortened URLs

The objective of a phishing campaign is to get the recipient to click on a malicious link. The attacker will often try to hide the malicious links with URL shorteners, such as bit.ly. You can use a service like unshorten.it to expand back the link before clicking on it.

Unfamiliar Sender and/or Email

More often than not, the fraudster will email you from an unfamiliar email that may or may not resemble the person or entity he’s trying to impersonate.

Always verify the sender’s email before clicking on a link or opening an attachment, even if their “display name” is known. The fraudster may choose a display name familiar to the victim but send the email itself from an unrelated email, e.g., they will email you as Mary Johnson from HR, but if you look closely, the sender’s email is ‘scam101@gmail.com’.

Generic Greetings

While generic greetings may be somewhat common in a business setting when emailing, e.g., an entire department where the sender doesn’t have a specific contact, phishing emails employ unusually generic greetings since the same email will be sent to millions of people.

Expressions like “dear customer” or “dear account holder” and mentions of “your carrier” or “your Internet service provider” can be red flags in situations where you expect the sender to know your name.

Business Emails Compromise (BEC)

Attack on business people generally entails compromising the account of executives and sending emails to employees requesting payments to be made to the fraudster’s account as if it were a business transaction.

These attacks can cost quite a bit of money since businesses routinely wire large sums of cash to suppliers, etc. The FBI recorded losses of over $1.8 billion in about 20,000 occurrences in 2020, about $90,000 per occurrence.

They also report that the sophistication of these attacks is increasing. In the early 2010s, the attack consisted of spoofing company executives and requesting wire transfers to fraudulent locations.

Today the attack has evolved to include identity theft from other, non-related people. The scammer phishes an initial victim and manages to get scans of their ID. They use the stolen ID to open a bank account in their name and receive the wire from the business and then convert it to cryptocurrency.

Misspelled Addresses and Subdomains

Scammers will try to buy similar-looking domains to those they are imitating, hoping that a distracted victim won’t realize the difference between ‘amazon.com’ and ‘amazom.com’.

In fact, they can go one step further and use similar-looking, non-ASCII characters to create nearly identical domains. For example, the Cyrillic character “а” looks a lot like the Latin character “a”. This is known as an IDM homograph attack.

An attacker could register the domain using the Cyrillic characters to make it look like Amazon’s domain, like so: аmаzon.com (the “a” are the Cyrillic character, not the Latin “a”).

Non-Latin addresses need to be encoded in a format known as Punycode before they are resolved by the DNS servers. Most modern browsers will show the Punycode translation when you navigate to those domains, so confirm you’re at the right website when entering sensitive information.

(The spoof Amazon domain from before would turn into http://www.xn--mzon-43db.com/. Test it yourself: on an updated version of Chrome or Firefox, copy and paste on your address bar.)

If they can’t have a similar-looking domain, they will often create subdomains to make the website look more trustworthy, such as ‘paypal.secure.com’ instead of ‘paypal.com’.

Insecure Connections

Pretty much any company that cares about its users’ security will encrypt the traffic to their website. It’s easy to verify that you are on a secure website by looking for the HTTPS on the address bar of your browser. If the page you are visiting doesn’t have the lock, you may be on a phishing website.

Future of Phishing

Phishing attacks are only getting more creative, and most email filters can only deal with emails similar to what they’ve seen before (even then, it might be of your interest to read how Auth0 automates phishing responses).

Not only that, because these attacks are so broad, the attacker has an incredible amount of data of what works and what doesn’t. They can tweak their campaigns over time, increasing their success rate over time.

Spear-phishing is even more difficult to prevent and more dangerous because targets are high-profile individuals (i.e., leadership roles), with the rewards justifying the extra time spent tailoring the email to fewer people.

Oliveira says that “there is no way of completely eliminating the threat of phishing, for the same reason that we can never eliminate deception from the physical world.”

It’s very hard to change humans. We can make incremental improvements with training and awareness, and that is always welcomed.

However, we can also use technology to promote even greater changes, like Google did when they completely eliminated phishing attacks among their 85,000 employees by using U2F tokens. If you wish to implement it on your applications, Auth0 supports WebAuthn with FIDO security keys for multi-factor authentication.

About the author

Arthur Bellore

Cybersec Writer