The IETF OAuth Working Group is always hard at work creating and improving standards in the identity space. In this post, we will take a look at the latest draft for the JWT Best Current Practices document. This document describes common pitfalls and attacks related to the use of JWTs, and how to implement mitigations against them. Read on to learn more!

“Learn about the most common attacks against JWTs and how to guard against them!”

Tweet This

Introduction

The JSON Web Token (JWT) specification is an open standard (RFC 7519) that describes a JSON-based format for transferring claims between parties. Complimentary standards such as JSON Web Key (RFC 7517), JSON Web Signature (RFC 7515), JSON Web Encryption (RFC 7516), and JSON Web Algorithms (RFC 7518), can be used to extend JWTs with verification and encryption capabilities.

JWTs can be used for many different purposes. One of them is to transfer authentication and authorization claims between parties. For example, users who have authenticated with an identity provider may hold in their power a set of signed JWT claims that can be used by an application to confirm their identity.

In the identity space, JWTs are required by the OpenID Connect standard, a specification that relies on the OAuth2 framework to provide a well-defined authentication layer.

Simpler examples of JWTs in the wild are encrypted or signed tokens that can be used to store claims on browsers and mobile clients. These claims can easily be verified by receivers through shared secrets or public keys.

The JWT specification allows for custom private claims, making JWTs a good tool for exchanging any sort of validated or encrypted data that can easily be encoded as JSON.

If you want to learn more about JSON Web Tokens in general, their use in the industry, or the implementation details of the algorithms and libraries, do check the free JWT Handbook below.

Interested in getting up-to-speed with JWTs as soon as possible?

Download the free ebook

JWTs, like any other tool, have their own pitfalls and common attacks. The JSON Web Token Current Best Practices document attempts to enumerate them and provide clear details on how to avoid them. We will now go over the attacks and pitfalls, and later take a look at mitigations and best practices.

Pitfalls and Common Attacks

Before taking a look at the first attack, it is important to note that many of these attacks are related to the implementation, rather than the design, of JSON Web Tokens. This does not make them less critical. It is arguable whether some of these attacks could be mitigated, or removed, by changing the underlying design. For the moment, the JWT specification and format is set in stone, so most changes happen in the implementation space (changes to libraries, APIs, programming practices and conventions).

It is also important to have a basic idea of the most common representation for JWTs: the JWS Compact Serialization format. Unserialized JWTs have two main JSON objects in them: the header and the payload.

The header object contains information about the JWT itself: the type of token, the signature or encryption algorithm used, the key id, etc.

The payload object contains all the relevant information carried by the token. There are several standard claims, like sub (subject) or iat (issued at), but any custom claims can be included as part of the payload.

These objects are encoded using the JWS Compact Serialization format to produce something like this:

eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJzdWIiOiIxMjM0NTY3ODkwIiwibmFtZSI6IkpvaG4gRG9lIiwiaWF0IjoxNTE2MjM5MDIyfQ.XbPfbIHMI6arZ3Y922BhjWgQzWXcXNrz0ogtVhfEd2oThis is a signed JWT. Signed JWTs in compact format are simply the header and payload objects encoded using Base64-URL encoding and separated by a dot (.). The last part of the compact representation is the signature. In other words, the format is:

[Base64-URL encoded header].[Base64-URL encoded payload].[Signature]This only applies to signed tokens. Encrypted tokens have a different serialized compact format that also relies on Base64-URL encoding and dot-separated fields.

If you want to play with JWTs and see how they are encoded/decoded, check JWT.io.

"alg: none" Attack

As we mentioned before, JWTs carry two JSON objects with important information, the header and the payload. The header includes information about the algorithm used by the JWT to sign or encrypt the data contained in it. Signed JWTs sign both the header and the payload, while encrypted JWTs only encrypt the payload (the header must always be readable).

In the case of signed tokens, although the signature does protect the header and payload against tampering, it is possible to rewrite the JWT without using the signature and changing the data contained in it. How does this work?

Take for instance a JWT with a certain header and payload. Something like this:

header: { alg: "HS256", typ: "JWT" }, payload: { sub: "joe" role: "user" }

Now, let's say you encode this token into its compact serialized form with a signature and a signing key of value "secret". We can use JWT.io for that. The result is:

eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJzdWIiOiJqb2UiLCJyb2xlIjoidXNlciJ9.vqf3WzGLAxHW-X7UP-co3bU_lSUdVjF2MKtLtSU1kzUGo ahead and paste that on JWT.io.

Now, since this is a signed token, we are free to read it. This also means we could construct a similar token with slightly changed data in it, although in that case, we would not be able to sign it unless we knew the signing key. Let's say attackers do not know the signing key, what could they do? In this type of attack, the malicious users could attempt to use a token with no signature! How does that work?

First, the attackers modify the token. For example:

header: { alg: "none", typ: "JWT" }, payload: { sub: "joe" role: "admin" }

Encoded:

eyJhbGciOiJub25lIiwidHlwIjoiSldUIn0.eyJzdWIiOiJqb2UiLCJyb2xlIjoiYWRtaW4ifQ.Note that this token does not include a signature ("alg": "none") and that the role claim of the payload has been changed. If attackers manage to use this token successfully, they may achieve an escalation of privilege attack! Why would an attack like this work? Let's take a look at how some hypothetical JWT library could work. Let's say we have a decoding function that looks like this:

function jwtDecode(token, secret) { // (...) }

This function takes an encoded token and a secret and attempts to verify the token and then return the decoded data in it. If verification fails, it throws an exception. To pick the right algorithm for verification, the function relies on the alg claim from the header. This is where the attack succeeds. In the past, many libraries relied on this claim to pick the verification algorithm, and, as you may have guessed, in our malicious token the alg claim is none. That means that there's no verification algorithm, and the verification step always succeeds.

As you can see, this is a classic example of an attack that relies on a certain ambiguity of the API of a specific library, rather than a vulnerability in the specification itself. Even so, this is a real attack that was possible in several different implementations in the past. For this reason, many libraries today report "alg": "none" tokens as invalid, even though there's no signature in place. There are other possible mitigations for this type of attack, the most important one being to always check the algorithm specified in the header before attempting to verify a token. Another one is to use libraries that require the verification algorithm as an input to the verification function, rather than rely on the alg claim.

RS256 Public-Key as HS256 Secret Attack

This attack is similar to the "alg": "none" attack and also relies on ambiguity in the API of certain JWT libraries. Our sample token will be similar to the one for that attack. In this case, however, rather than removing the signature, we will construct a valid signature that the verification library will also consider valid by relying on a loophole in many APIs. First, consider the typical function signature of some JWT libraries for the verification function:

function jwtDecode(token, secretOrPublicKey) { // (...) }

As you can see here, this function is essentially identical to the one from the "alg": "none" attack. If verification is successful, the token is decoded and returned, otherwise, an exception is thrown. In this case, however, the function also accepts a public key as the second parameter. In a way, this makes sense: both the public key and the shared secret are usually strings or byte arrays, so from the point of view of the necessary types for that function argument, a single argument can represent both a public key (for RS, ES, or PS algorithms) and a shared secret (for HS algorithms). This type of function signature is common for many JWT libraries.

Now, suppose the attacker gets an encoded token signed with an RSA key pair. It looks like this:

eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJzdWIiOiJqb2UiLCJyb2xlIjoidXNlciJ9.QDjcv11Kcb69THVLKMErYqzy9htWlCDtBdonVR5SX4geZa_R8StjwUuuskveUsdJVgjgXwMso7pguAJZzoE9LEr9XCxau7SF1ddws4ONiqxSVXZbO0pSgbKm3FpkVz4Jyy4oNTs-bIYyE0xf8snFlT1MbBWcG5psnuG04IEle4sDecoded:

header: { "alg": "RS256", "typ": "JWT" }, payload: { "sub": "joe", "role": "user" }

This token is signed with an RSA key-pair. RSA signatures are produced with the private key, while verification is done with the public key. Whoever verifies the token in the future could make a call to our hypothetical jwtDecode function from before like so:

const publicKey = '...'; const decoded = jwtDecode(token, publicKey);

But here's the problem: the public key is, like the name implies, usually public. Attackers may get their hands on it, and that should be OK. But what if the attackers were to create a new token using the following scheme. First, the attackers modify the header and choose HS256 as the signing algorithm:

header: { "alg": "HS256", "typ": "JWT" }

Then they escalate permissions by changing the role claim in the payload:

payload: { "sub": "joe", "role": "admin" }

Now, here's the attack: the attacker proceeds to create a newly encoded JWT by using the public key, which is a simple string, as the HS256 shared secret! In other words, since the shared secret for HS256 can be any string, even a string like the public key for the RS256 algorithm can be used for that.

Now if we go back to our hypothetical use of the jwtDecode function from before:

const publicKey = '...'; const decoded = jwtDecode(token, publicKey);

We can now clearly see the problem, the token will be considered valid! The public key will get passed to the jwtDecode function as the second argument, but rather than being used as a public key for the RS256 algorithm, it will be used as a shared secret for the HS256 algorithm. This is caused by the jwtDecode function relying on the alg claim from the header to pick the verification algorithm for the JWT. And the attacker changed that:

header: { "alg": "HS256", // <-- changed by the attacker from RS256 "typ": "JWT" }

Just like in the "alg": "none" case, relying on the alg claim combined with a bad or confusing API can result in a successful attack by a malicious user.

Mitigations against this attack include passing an explicit algorithm to the jwtDecode function, checking the alg claim, or using APIs that separate public-key algorithms from shared secret algorithms.

Weak HMAC Keys

HMAC algorithms rely on a shared secret to produce and verify signatures. Some people assume that shared secrets are similar to passwords, and in a sense, they are: they should be kept secret. However, that is where the similarities end. For passwords, although the length is an important property, the minimum required length is relatively small compared to other types of secrets. This is a consequence of the hashing algorithms that are used to store passwords (along with a salt) that prevent brute force attacks in reasonable timeframes.

On the other hand, HMAC shared secrets, as used by JWTs, are optimized for speed. This allows many sign/verify operations to be performed efficiently but make brute force attacks easier. So, the length of the shared secret for HS256/384/512 is of the utmost importance. In fact, JSON Web Algorithms defines the minimum key length to be equal to the size in bits of the hash function used along with the HMAC algorithm:

"A key of the same size as the hash output (for instance, 256 bits for "HS256") or larger MUST be used with this algorithm." - JSON Web Algorithms (RFC 7518), 3.2 HMAC with SHA-2 Functions

In other words, many passwords that could be used in other contexts are simply not good enough for use with HMAC-signed JWTs. 256-bits equals 32 ASCII characters, so if you are using something human readable, consider that number to be the minimum number of characters to include in the secret. Another good option is to switch to RS256 or other public-key algorithms, which are much more robust and flexible. This is not simply a hypothetical attack, we have shown that brute force attacks for HS256 are simple enough to perform if the shared secret is too short.

Wrong Stacked Encryption + Signature Verification Assumptions

Signatures provide protection against tampering. That is, although they don't protect data from being readable, they make it immutable: any changes to the data result in an invalid signature. Encryption, on the other hand, makes data unreadable unless you know the shared key or private key.

For many applications, signatures are all that is necessary. However, for sensitive data, encryption may be required. JWTs support both: signatures and encryption.

It is very common to wrongly assume that encryption also provides protection against tampering in all cases. The rationale for this assumption is usually something like this: "if the data can't be read, how would an attacker be able to modify it for their benefit?". Unfortunately, this underestimates attackers and their knowledge of the algorithms involved in the process.

Some encryption/decryption algorithms produce output regardless of the validity of the data passed to them. In other words, even if the encrypted data was modified, something will come out of the decryption process. Blindly modifying data usually results in garbage as output, but to a malicious attacker, this may be enough to get access to a system. For example, consider a JWT payload that looks like this:

{ "sub": "joe", "admin": false }

As we can see here, the admin claim is simply a boolean. If attackers can manage to produce a change in the decrypted data that results in that boolean value being flipped, they may successfully execute an escalation of privileges attack. In particular, attackers that have ample time windows to perform attacks can try as many changes to encrypted data as they like, without having the system discard the token as invalid before processing it. Other attacks may involve feeding invalid data to subsystems that expect data to be already sanitized at that point, triggering bugs, failures, or serving as the entry point for other types of attacks.

For this reason, JSON Web Algorithms only defines encryption algorithms that also include data integrity verification. In other words, as long as the encryption algorithm is one of the algorithms sanctioned by JWA, it may not be necessary for your application to stack an encrypted JWT on top of a signed JWT. However, if you encrypt a JWT using a non-standard algorithm, you must either make sure that data integrity is provided by that algorithm, or you will need to nest JWTs, using a signed JWT as the innermost JWT to ensure data integrity.

Nested JWTs are explicitly defined and supported by the specification. Although unusual, they may also appear in other scenarios, like sending a token issued by some party through a third party system that also uses JWTs.

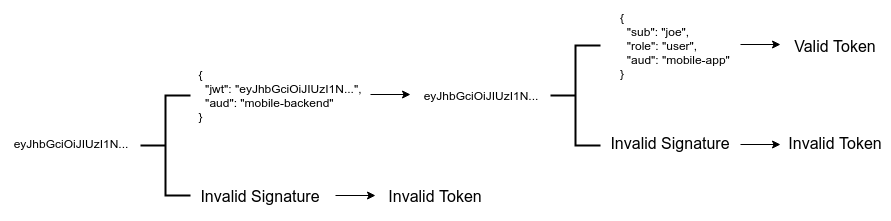

A common mistake in these scenarios is related to the validation of the nested JWT. To make sure that data integrity is preserved, and that data is properly decoded, all layers of JWTs must pass all validations related to the algorithms defined in their headers. In other words, even if the outermost JWT can be decrypted and validated, it is also necessary to validate (or decrypt) all the innermost JWTs. Failing to do so, especially in the case of an outermost encrypted JWT carrying an innermost signed JWT, can result in the use of unverified data, with all the associated security issues related to that.

Invalid Elliptic-Curve Attacks

Elliptic-curve cryptography is one of the public-key algorithm families supported by JSON Web Algorithms. Elliptic-curve cryptography relies on the intractability of the elliptic-curve discrete logarithm problem, a mathematical problem that cannot be solved in reasonable times for big enough numbers. This problem prevents the recovery of the private key from a public key, an encrypted message, and its plaintext. When compared to RSA, another public-key algorithm which is also supported by JSON Web Algorithms, elliptic-curves provide a similar level of strength while requiring smaller keys.

Elliptic-curves, as required for cryptographic operations, are defined over finite fields. In other words, they operate on sets of discrete numbers (rather than all real numbers). This means that all numbers involved in cryptographic elliptic-curve operations are integers.

All mathematical operations of elliptic-curves result in valid points over the curve. In other words, the math for elliptic-curves is defined in such a way that invalid points are simply not possible. If an invalid point is produced, then there is an error in the inputs to the operations. The main arithmetic operations on elliptic curves are:

- Point addition: adding two points on the same curve resulting in a third point on the same curve.

- Point doubling: adding a point to itself, resulting in a new point on the same curve.

- Scalar multiplication: multiplying a single point on the curve by a scalar number, defined as repeatedly adding that number to itself

ktimes (wherekis the scalar value).

All cryptographic operations on elliptic-curves rely on these arithmetic operations. Some implementations, however, fail to validate the inputs to them. In elliptic-curve cryptography, the public key is a point on the elliptic curve, while the private key is simply a number that sits within a special, but very big, range. If inputs to these operations are not validated, the arithmetic operations may produce seemingly valid results even when they are not. These results, when used in the context of cryptographic operations such as decryption, can be used to recover the private key. This attack has been demonstrated in the past. This class of attacks is known as invalid curve attacks. Good-quality implementations always check that all inputs passed to any public function are valid. This includes verifying that public-keys are a valid elliptic-curve point for the chosen curve and that private keys sit inside the valid range of values.

Substitution Attacks

Substitution attacks are a class of attacks where an attacker manages to intercept at least two different tokens. The attacker then manages to use one or both of these tokens for purposes other than the one they were intended for.

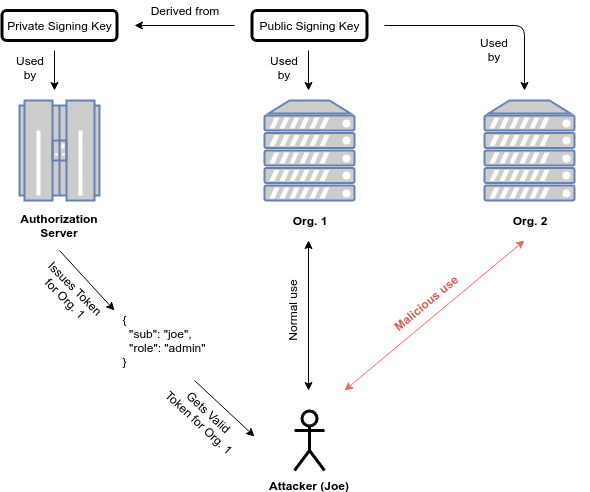

There are two types of substitution attacks: same recipient (called cross JWT in the draft), and different recipient.

Different Recipient

Different recipient attacks work by sending a token intended for one recipient to a different recipient. Let's say there is an authorization server that issues tokens for a third party service. The authorization token is a signed JWT with the following payload:

{ "sub": "joe", "role": "admin" }

This token can be used against an API to perform authenticated operations. Furthermore, at least when it comes to this service, the user joe has administrator level privileges. However, there is a problem with this token: there is no intended recipient or even an issuer in it. What would happen if a different API, different from the intended recipient this token was issued for, used the signature as the only check for validity? Let's say there's also a user joe in the database for that service or API. The attacker could send this same token to that other service and instantly gain administrator privileges!

To prevent these attacks, token validation must rely on either unique, per-service keys or secrets, or specific claims. For instance, this token could include an aud claim specifying the intended audience. This way, even if the signature is valid, the token cannot be used on other services that share the same secret or signing key.

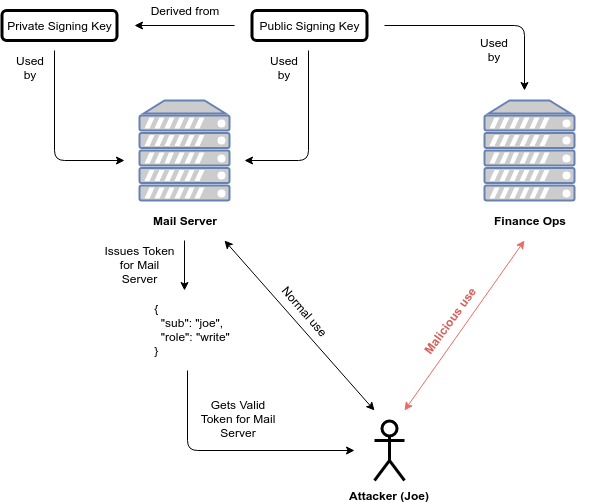

Same Recipient/Cross JWT

This attack is similar to the previous one, but rather than relying on a token issued for a different recipient, in this case, the recipient is the same. What changes, in this case, is that the attacker sends the token to a different service rather the one intended for (inside the same company or service provider).

Let's imagine a token with the following payload:

{ "sub": "joe", "perms": "write", "aud": "cool-company/user-database", "iss": "cool-company" }

This token looks much more secure. We have an issuer (iss) claim, an audience (aud) claim, and a permissions (perm) claim. The API for which this token was issued checks all of these claims even if the signature of the token is valid. This way, even if attackers manage to get their hands on a token signed with the same private key or secret, they cannot use it to operate on this service if it's not intended for it.

However, cool-company has other public services. One of these services, the cool-company/item-database service, has recently been upgraded to check claims along with the token signature. However, during the upgrades, the team in charge of selecting the claims that would be validated made a mistake: they did not validate the aud claim correctly. Rather than checking for an exact match, they decided to check for the presence of the cool-company string. It turns out that the other service, the hypothetical cool-company/user-database service, emits tokens that also pass this check. In other words, attackers could use the token intended for the user-database service in place for the token for the item-database service. This would grant the attackers write permissions to the item database when they should only have write permissions for the user database!

Mitigations and Best Practices

We've had a look at common attacks using JWTs, now let's take a look at the current list of best practices. All of these attacks can be successfully prevented by following these recommendations.

Always Perform Algorithm Verification

The "alg": "none" attack and the "RS256 public-key as HS256 shared secret" attack can be prevented by this mitigation. Every time a JWT is to be validated, the algorithm must be explicitly selected to prevent giving attackers control. Libraries used to rely on the header alg claim to select the algorithm for validation. From the moment attacks like these were seen in the wild, libraries have switched to at least provide the option of explicitly specifying the selected algorithms for validation, disregarding what is specified in the header. Still, some libraries provide the option of using whatever is specified in the header, so developers must take care to always use explicit algorithm selection.

Use Appropriate Algorithms

Although the JSON Web Algorithms spec declares a series of recommended and required algorithms, picking the right one for a specific scenario is still up to the users. For example, a JWT signed with an HMAC signature may be enough for storing a small token from your single-server, single-page web application in a user's browser. In contrast, a shared secret algorithm would be sorely inconvenient in a federated identity scenario.

Another way of thinking about this is to consider all JWTs invalid unless that validation algorithm is acceptable to the application. In other words, even if the validating party has the keys and the means necessary for validating a token, it should still be considered invalid if the validation algorithm is not the right one for the application. This is also another way of saying what we mentioned in our previous recommendation: always perform algorithm verification.

Always Perform All Validations

In the case of nested tokens, it is necessary to always perform all validation steps as declared in the headers of each token. In other words, it is not sufficient to decrypt or validate the outermost token and then skip validation for the inner ones. Even in the case of only having signed JWTs, it is necessary to validate all signatures. This is a source of common mistakes in applications that use JWTs to carry other JWTs issued by external parties.

Always Validate Cryptographic Inputs

As we have shown in the attacks section before, certain cryptographic operations are not well defined for inputs outside their range of operation. These invalid inputs can be exploited to produce unexpected results, or to extract sensitive information that may lead to a full compromise (i.e. the attackers getting hold of a private key).

In the case of elliptic-curve operations, our example from before, libraries must always validate public-keys before using them (i.e. confirming they represent a valid point on the selected curve). These types of checks are normally handled by the underlying cryptographic library. Developers must make sure that their library of choice performs these validations, or they must add the necessary code to perform them at the application level. Failing to do so can result in a compromise of their private key(s).

Pick Strong Keys

Although this recommendation applies to any cryptographic key, it is still ignored many times. As we have shown above, the minimum necessary length for HMAC shared secrets is often overlooked. But even if the shared secret were long enough, it must also be fully random. A long key with a bad level of randomness (a.k.a. "entropy") can still be brute-forced or guessed. To ensure this is not the case, key generating libraries should rely on cryptographic-quality pseudo-random number generators (PRNGs) properly seeded during initialization. At best, a hardware number generator may be used.

This recommendation applies to both shared-key algorithms and public-key algorithms. Furthermore, in the case of shared key algorithms, human-readable passwords are not considered good enough and are vulnerable to dictionary attacks.

Validate All Possible Claims

Some of the attacks we have discussed rely on incorrect validation assumptions. In particular, they rely on signature validation or decryption as the only means of validation. Some attackers may get access to correctly signed or encrypted tokens that can be used for malicious purposes, usually by using them in unexpected contexts. The right way to prevent these attacks is to only consider a token valid when both the signature and the content are valid. For this reason, claims such as sub (subject), exp (expiration time), iat (issued at), aud (audience), iss (issuer), nbf (not valid before) are of the utmost importance and should always be validated when present. If you are creating tokens, consider adding as many claims as necessary to prevent its use in different contexts. In general, sub, iss, aud, and exp are always useful and should be present.

Use The typ Claim To Separate Types Of Tokens

Although most of the time the typ claim has a single value (JWT), it can also be used to separate different types of application specific JWTs. This can be useful in case your system must handle many different types of tokens. This claim can also prevent misuse of a token in a different context by means of an additional claim check. The JWS standard explicitly allows for application-specific values of the typ claim.

Use Different Validation Rules For Each Token

This practice sums up many of the ones that have been enumerated before. To prevent attacks it is of key importance to make sure each token that is issued has very clear and specific validation rules. This not only means using the typ claim when appropriate, or validating all possible claims such as iss or aud, but it also implies avoiding key reuse for different tokens where possible or using different custom claims or claim formats. This way, tokens that are meant to be used in a single place cannot be substituted by other tokens with very similar requirements.

In other words, rather than using the same private key for signing all kinds of tokens, consider using different private keys for each subsystem of your architecture. You can also make claims more specific by specifying a certain internal format for them. The iss claim, for instance, could be an URL of the subsystem that issued that token, rather than the name of the company, making it harder to be reused.

Aside: Delegating JWT Implementation to the Experts

JWTs are an integral part of the OpenID Connect standard, an identity layer that sits on top of the OAuth2 framework. Auth0 is an OpenID Connect certified identity platform. This means that if you pick Auth0 you can be sure it is 100% interoperable with any third party system that also follows the specification.

The OpenID Connect specification requires the use of the JWT format for ID tokens, which contain user profile information (such as the user's name and email) represented in the form of claims. These claims are statements about the user, which can be trusted if the consumer of the token can verify its signature.

While the OAuth2 specification doesn't mandate a format for access tokens, used to grant applications access to APIs on behalf of users, the industry has widely embraced the use of JWTs for these as well.

As a developer, you shouldn't have to worry about directly validating, verifying, or decoding authentication-related JWTs in your services. You can use modern SDKs from Auth0 to handle the correct implementation and usage of JWTs, knowing that they follow the latest industry best practices and are regularly updated to address known security risks.

For example, the Auth0 SDK for Single Page Applications provides a method for extracting user information from an ID Token, auth0.getUser.

If you want to try out the Auth0 platform, sign up for a free account and get started! With your free account, you will have access to the following features:

- Universal Login for Web, iOS & Android

- Up to 2 social identity providers (like Twitter and Facebook)

- Unlimited Serverless Rules

To learn more about JWTs, their internal structure, the different types of algorithms that can be used with them, and other common uses for them, check out the JWT Handbook.

Conclusion

JSON Web Tokens are a tool that makes use of cryptography. Like all tools that do so, and especially those that are used to handle sensitive information, they should be used with care. Their apparent simplicity may confuse some developers and make them think that using JWTs is just a matter of picking the right shared secret or public key algorithm. Unfortunately, as we have seen above, that is not the case. It is of the utmost importance to follow the best practices for each tool in your toolbox, and JWTs are no exception. This includes picking battle-tested, high-quality libraries; validating payload and header claims; choosing the right algorithms; making sure strong keys are generated; paying attention to the subtleties of each API; among other things. If all of this seems daunting, consider offloading some of the burdens to external providers. Auth0 is one such provider. If you cannot do this, consider these recommendations carefully, and remember: don't roll your own crypto, rely on tried and tested code.

“Don't be fooled by the apparent simplicity of JWTs, use them with care and follow the best current practices!”

Tweet This

About the author

Sebastian Peyrott

Senior Engineer