Our JavaScript history article sparked interesting comments regarding what really happened during the ECMAScript 4 era. Below you will find a more detailed perspective of what really went down between 1999 and 2008 in the world of JavaScript. Read on!

“A deeper look onto what really went on with ECMAScript 4”

Tweet This

A Short Recap

As we explained in detail in our JavaScript history piece, JavaScript was originally conceived as a "glue" programming language for designers and amateur programmers. It was meant to be a simple scripting language for the Web, one that could be used for animations, preliminary form checks and dynamic pages. Time showed, however, that people wanted to do much more with it.

A year after its release in 1995 Netscape took JavaScript to ECMA, a standards organization, to create a standard for JavaScript. In a way, this was a two-sided effort: on one hand, it was an attempt to keep implementors in check (i.e., keeping implementations compatible), and it was also a way for other players to be part of the development process without leaving room for classic "embrace, extend, extinguish" schemes.

A major milestone was finally reached in 1999 when ECMAScript 3 was released. This was the year of Netscape Navigator 6 and Internet Explorer 5. AJAX was just about to be embraced by the web development community. Although dynamic web pages were already possible through hidden forms and inner frames, AJAX brought a revolution in web functionality, and JavaScript was at its center.

To better understand what happened after 1999, we need to take a look at three key players: Netscape, Microsoft and Macromedia. Of these three, only Netscape and Microsoft were part of TC-39, the ECMAScript committee, in 1999.

Netscape

In 1999, some members of TC-39 were already working on ideas for what could be ECMAScript 4. In particular, Waldemar Horwat at Netscape had begun documenting a series of ideas and proposals for the future evolution of ECMAScript. The earliest draft, dated February, 1999 can be found in the Wayback Machine. An interesting look at the ideas for the next version of ECMAScript is outlined in the Motivation section:

JavaScript is not currently a general-purpose programming language. Its strengths are its quick execution from source (thus enabling it to be distributed in web pages in source form), its dynamism, and its interfaces to Java and other environments. JavaScript 2.0 is intended to improve upon these strengths, while adding others such as the abilities to reliably compose JavaScript programs out of components and libraries and to write object-oriented programs. - Waldemar Horwat's early JavaScript 2.0 proposal

However, Netscape would not be the first with a public implementation of these ideas. It would be Microsoft.

Microsoft

In 1999 Microsoft was focused on a revolution of its own: .NET. It was around the release of Internet Explorer 5 and ECMAScript 3 that Microsoft was getting ready to release the first version of the .NET Framework: a full development platform around a new set of libraries and a common language runtime, capable of providing a convenient execution environment for many different languages. The first exponents of .NET were C# and Visual Basic .NET: the first, an entirely new language inspired by Java and C++; the second, an evolution of its popular Visual Basic language, targeting the new platform. The .NET Framework included support for Microsoft's server-side programming framework: ASP.NET. It was perhaps natural that ASP.NET should provide a JavaScript-like language as part of its tools, and an implementation of a dynamic language such as JavaScript could very well serve as a natural demonstration of the capabilities of the common language runtime. Thus JScript .NET was born.

JScript .NET was introduced in 2000. It was slated as an evolution of JScript, the client-side scripting engine used by Internet Explorer, with a focus on performance and server-side uses, a natural fit for the .NET architecture and the ASP.NET platform. It would also serve to displace VBScript, another scripting language developed by Microsoft in the '90s with heavy inspiration from Visual Basic, normally used for server-side/desktop scripting tasks.

One of the design objectives of JScript .NET was to remain largely compatible with existing JScript code; in other words, mostly compatible with ECMAScript 3. There were implementation differences between JScript and Netscape's JavaScript; however it was Microsoft's stated objective to follow the standard. It was also one of the objectives from ECMAScript 4 to remain compatible with previous versions of the standard (in the sense that ECMAScript 3 code should run on ECMAScript 4 interpreters). ECMAScript 4 was, thus, a convenient evolution path for JScript .NET. Released from the constraints of browser development, the team behind JScript .NET could work faster and iterate at their discretion. JScript .NET became, much like Macromedia's ActionScript, another experimental implementation of many of the ideas behind ECMAScript 4.

In the words of the JScript .NET team: > (...) all the new features have been designed in conjunction with other ECMA members. It's important to note that the language features in the JScript .NET PDC release are not final. We're working with other ECMA members to finalize the design as soon as possible. In fact, there's an ECMA meeting this week at the PDC where we'll try to sort out some of the remaining issues. - Introducing JScript .NET

In contrast with the first versions of ActionScript, the first releases of JScript .NET in 2000 already included much more functionality from ECMAScript 4: classes, optional typing, packages and access modifiers were some of its new features.

Macromedia

As the Internet was becoming popular, spearheaded by Netscape and its Communicator suite, a different but no less important battle was taking place. Vector animation companies FutureWave Software and Macromedia had developed by 1995 two of the leading animation platforms: Macromedia Shockware and FutureWave FutureSplash.

From the beginning, Macromedia saw the importance of taking its product to the Web, so with help from Netscape it integrated its Shockwave Player into Netscape Navigator as a plugin. Much of the work required for having "external components" in the browser had already been done for Java, so the needed infrastructure was in place.

In November 1996, Macromedia acquired FutureSplash and promptly renamed it Flash. This made Macromedia the sole owner of the two most important vector-based animation tools for the Web: Shockwave and Flash. For a time, both players and authoring tools coexisted, but after a few years Flash emerged as the winner.

The combined power of the web platform, getting bigger and bigger by the day, and the push from content creators caused Flash to evolve rapidly. The next big step for animation software was to become a platform for interactive applications, much like Java offered at the moment, but catering to designers and with special focus on animation performance and authoring tools. The power of a certain programmability first came to Flash in version 2 (1997) with actions.

"Actions" were simple operations that could be triggered by user interaction. These operations did not resemble a full programming language. Rather, they were limited to simple "goto-style" operations in the animation timeline.

However, by version 4 (1999), actions had pretty much evolved into a programming language: loops, conditionals, variables and other typical language constructs were available. However, the limitations of the language were becoming apparent and Macromedia was in need of something more mature. As it turns out, browsers already had one such language: JavaScript. Catering to non-programmers and already with considerable mindshare, JavaScript was a sound choice.

Flash Player version 5 (2000) drew heavily from ECMAScript 3 for its scripting language. Combined with some of the constructs used for previous versions, this new language expanded actions with many tools from ECMAScript such as its prototype-based object model and weak typed variables. Many keywords (such as var) were also shared. This new language was called ActionScript.

By this year, Macromedia was committed to improving ECMAScript. The synergy between JavaScript in the browser and ActionScript in Flash was just what Macromedia needed: Macromedia got a powerful programming language, and at the same time tapped into the mindshare from the already-existing designer-oriented JavaScript community. It would be in Macromedia's best interest to see ECMAScript succeed.

Flash as a Platform

The power of vector-based animations, a convenient editor and a powerful programming language proved to be a killer combination. Not only were more and more end users installing the Flash Player plugin, but content creators were also producing ever more complex content. Flash was quickly becoming a tool for more than just animations; it was becoming a platform to deliver rich content, with complex business logic behind it. In a sense, Macromedia had a big advantage compared to the rest of the Web: it was the sole owner and developer of the platform. That meant it could iterate and improve on it and at a much quicker pace than the Web itself. Not only that, it also had the best authoring tools for visual and interactive content, and the mindshare of developers and designers dedicated to this type of content. All of this put Macromedia ahead of other players, even Sun and its Java language (with regards to Java applets in the browser).

The next natural step for Macromedia was to move forward. It had the best authoring tools and it was gaining developer mindshare. It was only logical to keep investing and advancing the development of its tools. And one of these tools was ActionScript. Macromedia saw with good eyes the ideas Netscape was putting forth in its ECMAScript 4 proposals document, and so began adopting many of them for their own language. At the same time, they knew it was in their best interest to not stray too far away from the general community of JavaScript developers, so they made a good effort to first become compliant with the ECMAScript 3 standard. It could only do them good: ECMAScript 4 was slated as the improvement JavaScript needed for bigger programs, and their community would certainly make use of that. Also, by leading the charge, they could have more leverage in the committee to push forward features that worked, or even new ideas. It was a sound plan.

Although interest in ECMAScript 4 eventually dwindled inside the committee, by 2003 Macromedia was ready to release its new version of ActionScript as part of Flash 7. ActionScript 2.0 brought compile-time type checks and classes, two slated features found in the ECMAScript 4 drafts, and improved compliance with ECMAScript 3.

The Years of Silence

TC-39 and ECMA were active between 1999 and 2003. Horwat's (Netscape) latest draft document is dated August 11, 2000. Macromedia and Microsoft continued independently based largely on this draft document, but no interoperability tests were performed at this stage. By 2003, work by the committee had all but stopped. This meant there was no real push for a new release of the ECMAScript standard. Although Macromedia was about to release ActionScript 2.0 in 2003 and Microsoft's .NET platform was flourishing, ECMAScript 4 was not moving forward.

It is important to note that at this stage, the drafts published by Horwat (Netscape) were not exhaustive enough to ensure compatibility between implementations. In other words, although ActionScript and JScript .NET were loosely based on the same drafts, they were not really compatible. Worse, code was already being developed using these implementations; code that could potentially become incompatible with the standard in the future. In a sense, this was not seen as a big problem, as ActionScript and JScript .NET were mostly isolated in their own platforms. Browser engines, for their part, had not advanced as much. Some extensions implemented by the big browsers, Internet Explorer and Netscape, were in use, but nothing big enough.

Two long years passed between when work halted in 2003 until it was resumed. In between several significant events took place:

- Internet Explorer, the free browser bundled with Windows by Microsoft, succeeded in crushing Netscape out of the browser market.

- Firefox was released by Mozilla in 2004.

- A new standard integrating XML processing into JavaScript was released in 2004: ECMAScript for XML (E4X, ECMA-357). It gained little traction outside certain browser implementations.

- Macromedia was acquired by Adobe in 2005.

Although it may seem these events are not related, they all played a part in the reactivation of TC-39.

TC-39 Comes Back to Life

The success of Internet Explorer on the desktop, due in great part to its bundling with Windows, forced Netscape's hand. In 1998, they released Netscape Communicator's source code and started the Mozilla project. By 2003, Microsoft had the majority of the browser market share and AOL, then owner of Netscape, announced major layoffs. The Mozilla project was to be spun off as an independent entity: the Mozilla Foundation. Mozilla would continue the development of Gecko (Netscape Navigators's layout engine) and SpiderMonkey. Soon, the Mozilla Foundation would shift its focus to the development of Firefox, a standalone browser without the bloat of the whole suite of applications that came bundled since Netscape's days. In an unexpected turn of events, Firefox's marketshare commenced to grow.

Microsoft, by the time Firefox was released, had mostly stagnated with regards to web development. Internet Explorer was the king, and .NET was making big inroads in the server market. JScript .NET, getting little traction and developer interest, was left mostly unchanged. In other words, Microsoft had no particular interest at this point in reviving ECMAScript: they controlled the browser, and JScript .NET was an afterthought. It would require some prodding to wake them up.

Macromedia, and then Adobe after its acquisition, started a push toward integration of their internal ActionScript work into ECMA in 2003. They had spent a considerable amount of technical effort on ActionScript, and it would only be in their best interest to see that work integrated into ECMAScript. They had the users, the implementation, and the experience to use as leverage inside the committee.

At this point, Brendan Eich, now part of Mozilla, was concerned about Microsoft's stagnation with regards to web technologies. He knew web development was based on consensus, and, at the moment, the biggest player was Microsoft. He needed their involvement if things were to move forward. Taking notice of Macromedia's renewed interest in restarting the work on ECMAScript 4, he realized now was a good time to get the ball rolling.

At the same time, there was interest in the community in standardizing a set of extensions to ECMAScript 3 meant to make it easier to manipulate XML data. A prototype of this had been developed by BEA Systems in 2002 and integrated into Mozilla Rhino, an alternative JavaScript engine written in Java. BEA Systems took their extension to ECMA; thus, ECMAScript for XML (E4X, ECMA-357) was born in 2004.

As E4X was an ECMA standard concerning ECMAScript, it was a good way to get the key players from TC-39 working back together. Eich used this opportunity to jump-start ECMAScript development again by pushing for a second E4X release in 2005. By the end of 2005, TC-39 was back at work on ECMAScript 4.

Although E4X was unrelated to the ECMAScript 4 proposal, it brought important ideas that would end up being used: namely namespaces and the

::operator.

Macromedia, now Adobe, took the work of TC-39 as a clear indication ActionScript was a safe bet. As work progressed, Adobe continued internal development of ActionScript at a fast pace, implementing many of the ideas discussed by the committee in short time. In 2006, Flash 9 was released, and with it ActionScript 3 was also out the door. The list of features integrated in it was extensive. On top of ActionScript 2 classes were added: optional typing, byte arrays, maps, compile time and runtime type checking, packages, namespaces, regular expressions, events, E4X, proxies, and iterators.

Adobe decided to take one more step to make sure things moved forward. In November 2006, Tamarin, Adobe's in-house ActionScript 3.0 engine (used in Flash 9), was released as open source and donated to the Mozilla Foundation. This was a clear indication that Adobe wanted ECMAScript to succeed and, if at all possible, to be as little different from ActionScript as possible.

A colorful fact of history is that Macromedia wanted to integrate Sun's J2ME JVM into Flash for ActionScript 3. The internal name for this project was "Maelstrom." For legal and strategic reasons this plan never came to fruition and Tamarin was born instead.

The Fallout

Work on ECMAScript was progressing and a draft design document with an outline of the expected features of ECMAScript 4 was released. The list of features had become quite long. By 2007, TC-39 was composed of more players than at the beginning. Of particular importance were newcomers Yahoo and Opera.

Microsoft, for their own part, were not sold on the idea of ECMAScript 4. Allen Wirfs-Brock, Microsoft's representative at TC-39, viewed the language as too complex for its own good. His reasons were strictly technical, though internally, Microsoft also had strategic concerns. Internal discussions at Microsoft eventually converged on a the idea that ECMAScript 4 should take a different course.

Another member of the committee, Douglas Crockford from Yahoo, also had his concerns about ECMAScript 4, although perhaps for different technical reasons. However, he had not been too vocal about them. Wirfs-Brock realized this and convinced Crockford it would be a good idea to voice his concerns. This created an impasse in the committee, which was now not in consensus. In Crockford's words:

Some of the people at Microsoft wanted to play hardball on this thing, they wanted to start setting up paper trails, beginning grievance procedures, wanting to do these extra legal things. I didn't want any part of that. My disagreement with ES4 was strictly technical and I wanted to keep it strictly technical; I didn't want to make it nastier than it had to be. I just wanted to try to figure out what the right thing to do was, so I managed to moderate it a little bit. But Microsoft still took an extreme position, saying that they refused to accept any part of ES4. So the thing got polarized, but I think it was polarized as a consequence of the ES4 team refusing to consider any other opinions. At that moment the committee was not in consensus, which was a bad thing because a standards group needs to be in consensus. A standard should not be controversial. - Douglas Crockford — The State and Future of JavaScript

Wirfs-Brock put forth the idea of somehow meeting at the middle. The committee decided to split into two work teams: one focused on finding a subset of ECMAScript 4 that was still useful but much easier to implement, and another team focused on moving forward with ECMAScript 4. Wirfs-Brock became the editor of the smaller, more focused standard, tentatively called ECMAScript 3.1. It is important to note that members from both teams worked in both groups, so they were not really separate in this sense.

As time passed, it became clear ECMAScript 4 was too big for its own weight. The group did not advance as much as they had hoped, and by 2008 many problems still had to be solved before a new standard could be drafted. The ECMAScript 3.1 team, however, had made considerable progress.

ECMAScript 4 is Dead, Long Live ECMAScript!

A meeting in Oslo, Norway, had been planned for the committee to establish a way forward. Before this meeting took place, Adobe, off the record, had made it clear they were planning to withdraw from ECMAScript 4 development, joining Microsoft and Yahoo in their stance. This was perhaps the result of seeing ECMAScript 4 become too different from ActionScript 3.

The iconic meeting took place in 2008. In it, the committee made the hard decision: ECMAScript 4 was dead. A new version of ECMAScript was to be expected, and a change in direction for future work was drafted. Brendan Eich broke the official news in an iconic email. The conclusions of this meeting were to:

- Focus work on ES3.1 with full collaboration from all parties, and target two interoperable implementations by early next year.

- Collaborate on the next step beyond ES3.1, which will include syntactic extensions but which will be more modest than ES4 in both semantic and syntactic innovation.

- Some ES4 proposals have been deemed unsound for the Web, and are off the table for good: packages, namespaces and early binding. This conclusion is key to Harmony.

- Other goals and ideas from ES4 are being rephrased to keep consensus in the committee; these include a notion of classes based on existing ES3 concepts combined with proposed ES3.1 extensions.

ECMAScript 3.1 was soon renamed to ECMAScript 5 to make it clear it was the way forward and that version 4 was not to be expected. Version 5 was finally released in 2009. All major browsers (including Internet Explorer) were fully compliant by 2012.

Of particular interest is the word "harmony" in Eich's e-mail. "Harmony" was the designated name for the new ECMAScript development process, to be adopted from ECMAScript 6 (later renamed 2015) onwards. Harmony would make it possible to develop complex features without falling into the same traps ECMAScript 4 experienced. Some of the ideas in ECMAScript 4 were recycled in Harmony. ECMAScript 6/2015 finally brought many of the big ideas from ECMAScript 4 to ECMAScript. Others were completely scrapped.

Wait, What Happened to ActionScript (and JScript .NET)?

Unfortunately for Adobe, the death of ECMAScript 4 and their decision to stop supporting it meant the large body of work they had performed to keep in sync with the ECMAScript 4 proposal was, at least in part, useless. Of course, they had a useful, powerful, and tested language in the form of ActionScript 3. The community of developers was quite strong as well. However, it is hard to argue against the idea that they bet on ECMAScript 4's success and lost. Tamarin, which was open-sourced to help adoption and progress of the new standard, was largely ignored by browsers. Mozilla initially attempted to merge it with SpiderMonkey, but they later realized performance suffered considerably for certain important use cases. Work was needed, and ECMAScript 4 was not complete, so it never got merged. Microsoft continued improving JScript. Opera and Google worked on their own clean-room implementations.

An interesting take on the matter was exposed by Mike Chambers, an Adobe employee:

ActionScript 3 is not going away, and we are not removing anything from it based on the recent decisions. We will continue to track the ECMAScript specifications, but as we always have, we will innovate and push the Web forward when possible (just as we have done in the past). - Mike Chambers' blog

It was the hope of ActionScript developers that innovation in ActionScript would drive features in ECMAScript. Unfortunately, this was never the case, and what later came to ECMAScript 2015 was in many ways incompatible with ActionScript.

JScript .NET, on the other hand, had been largely left untouched since the early 2000s. Microsoft had long realized developer uptake was just too low. It went into maintenance mode in .NET 2.0 (2005) and remains available only as a legacy product inside the latest versions of .NET. It does not support features added to .NET after version 1 (such as generics, delegates, etc.).

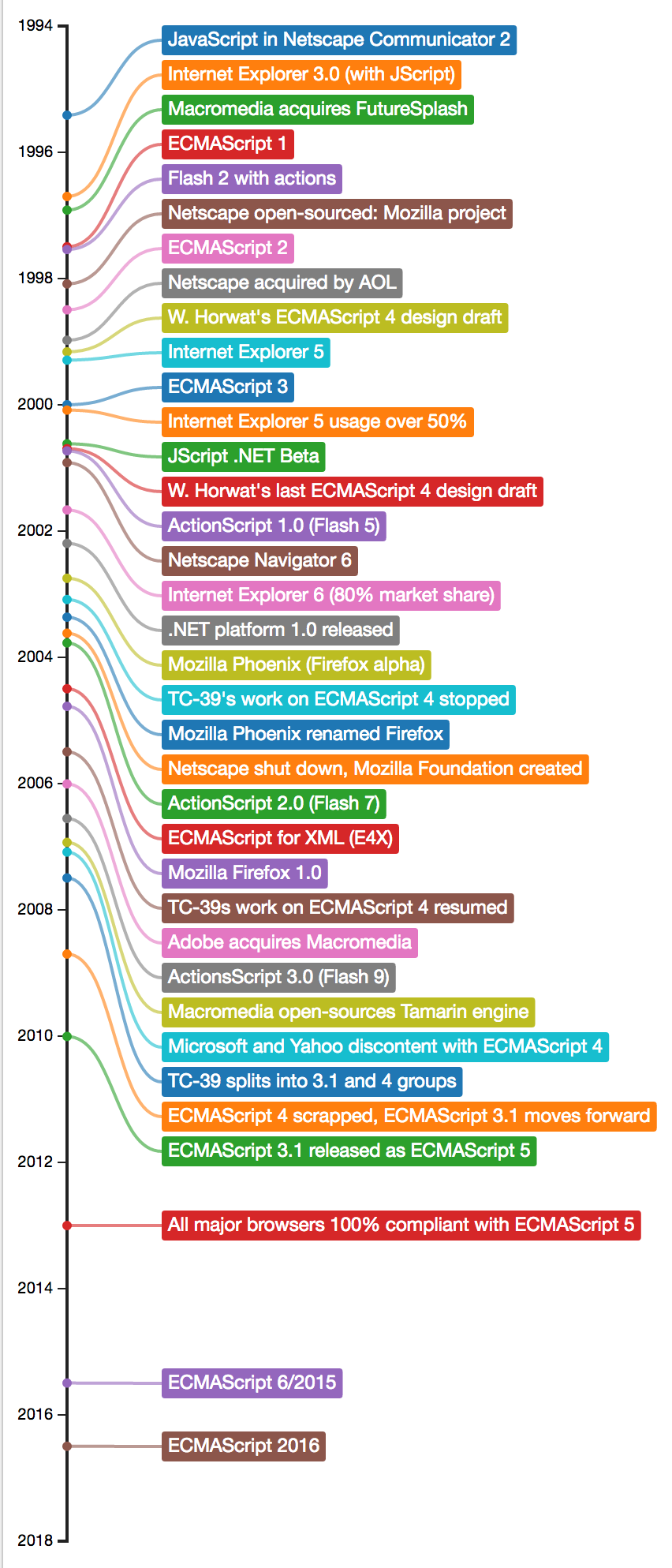

An ECMAScript timeline

Aside: JavaScript use at Auth0

At Auth0 we are heavy users of JavaScript. From our Lock library to our back end, JavaScript powers the core of our operations. We find its asynchronous nature and the low entry barrier for new developers essential to our success. We are eager to see where the language is headed and the impact it will have in its ecosystem.

Sign up for a free Auth0 accountand take a firsthand look at a production-ready ecosystem written in JavaScript. And don't worry, we have client libraries for all popular frameworks and platforms!

Auth0 offers a generous free tier to get started with modern authentication.

Recently, we have released a product called Auth0 Extend. This product enable companies to provide to their customers an easy to use extension point that accepts JavaScript code. With Auth0 Extend, customers can create custom business rules, scheduled jobs, or connect to the ecosystem by integrating with other SaaS systems, like Marketo, Salesforce, and Concur. All using plain JavaScript and NPM modules.

Conclusion

JavaScript has a bumpy history. The era of ECMAScript 4 development (1999-2008) is of particular value to language designers and technical committees. It serves as a clear example of how aiming for a release too big for its own weight can result in development hell and stagnation. It is also a stark reminder that even when you have an implementation and are at the forefront of development, things can go in a completely different direction (Adobe, Microsoft). Being cutting-edge is always a bet. On the other hand, the new process established by the Harmony proposal has started to show progress, and where ECMAScript 4 failed in the past, the newer ECMAScript has succeeded. Progress cannot be stopped when it comes to the Web. Exciting years are ahead, and they cannot come soon enough.

About the author

Sebastian Peyrott

Senior Engineer