JSON Web Tokens, or JWTs, are a cornerstone of modern application security and API protection. You've likely encountered them when implementing login flows, securing microservice communication, or working with standards like OAuth 2.0 and OpenID Connect. Their popularity, however, has given rise to a series of persistent myths and dangerous anti-patterns.

Many developers treat JWTs as a magical black box, leading to implementations that are either insecure or overly complex. Believing these myths can expose your application to significant vulnerabilities.

In this article, we will dissect and debunk five of the most common misconceptions about JWTs. By understanding what a JWT is—and what it isn't—you can leverage its power correctly and build more secure and robust systems.

Ready to see JWTs in action? Watch this quick video for a visual overview of how JSON Web Tokens work and why misconceptions around them are so common.

Myth 1: A JWT Is Just Another Name for a Token

One of the most fundamental misunderstandings is that "token" and "JWT" are synonymous. While a JWT is a type of token, not all tokens are JWTs.

A "token" in the general sense is simply a piece of data that represents a fact, usually an authorization grant. Historically, many of these tokens have been opaque strings. An opaque token is a random, meaningless string from the client's perspective. It acts as a reference, like a ticket stub. To get any information from it (like who the user is or what permissions they have), the receiving server must make a call back to the issuing server. Here is an example of an opaque token:

w3VzBypV4S1zaYd1-390AFda9d1t3-A4fWsdr23as

In contrast, a JSON Web Token (JWT) is a structured token. As defined in RFC 7519, a JWT is a compact, URL-safe means of representing claims to be transferred between two parties. It's not opaque; it's a self-contained JSON object that is digitally signed or encrypted.

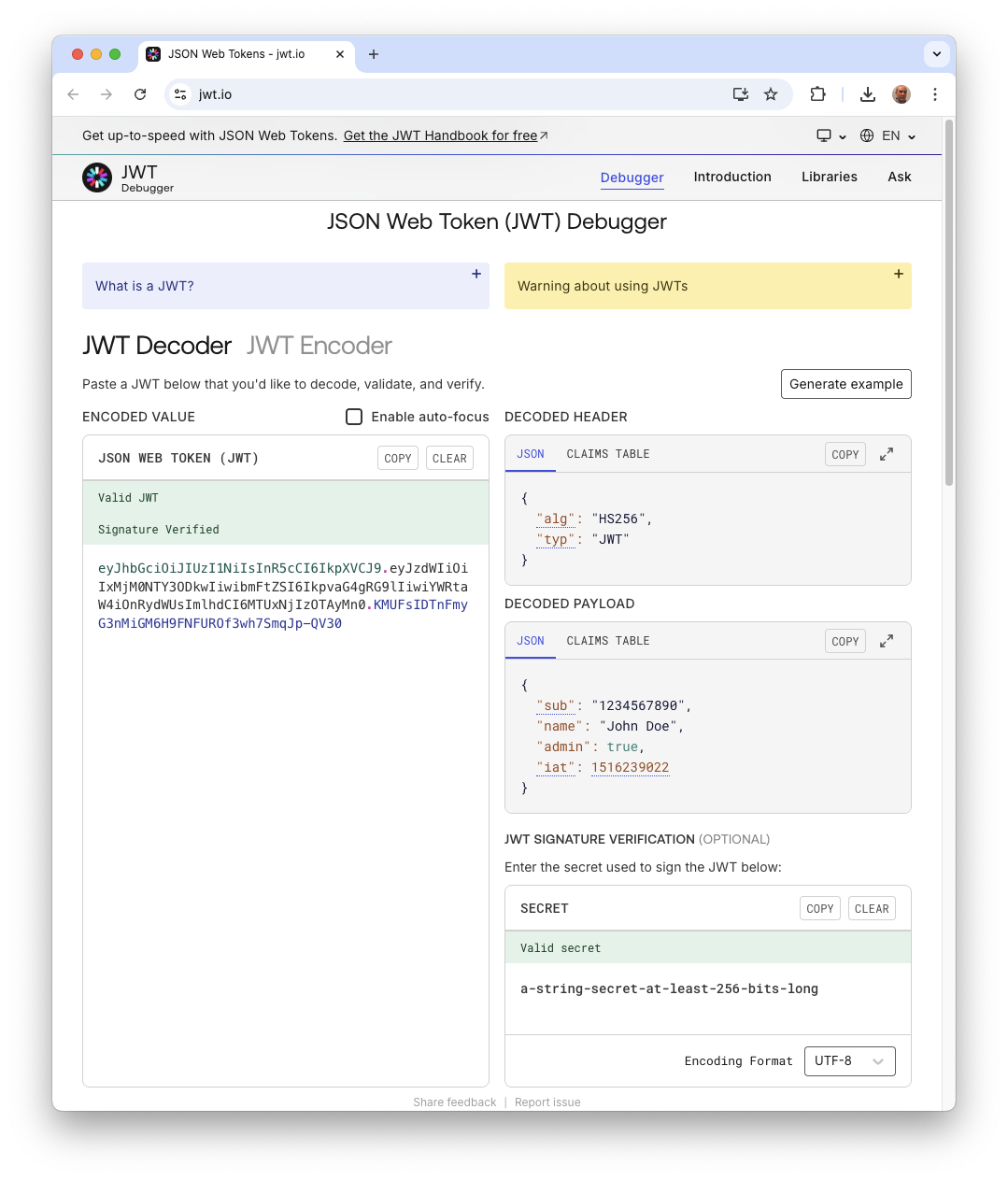

To learn more about JWTs, check out the JWT Handbook and use jwt.io to decode them.

Because it's self-contained, a service that trusts the issuer can validate a JWT and use its claims without needing to contact the issuer. This is the core benefit of JWTs: stateless, decentralized validation.

Myth 2: JWT and Access Token Are Interchangeable Terms

This myth often follows the first. In OAuth 2.0 terminology, an access token is a credential used by a client to access protected resources. The crucial detail is that the OAuth 2.0 specification does not mandate a specific format for access tokens. They can be opaque tokens, or they can be JWTs.

So, why the confusion? JWTs have become a very popular format for access tokens. The benefits are clear:

- A resource server (e.g., a web API application) can validate a JWT-based access token without calling the authorization server on every request. It just needs the issuer's public key to check the signature.

- The token itself can carry essential data, such as the user ID and permissions (scopes), reducing the need for extra database lookups.

However, an authorization server could just as easily issue an opaque access token and require resource servers to validate it via an introspection endpoint. This stateful approach offers a major benefit: the token can be revoked instantly.

As a takeaway, remember that an access token is a concept—a key that unlocks a door. A JWT is a format for that key. You can have an access token that is not a JWT, but you can't say a JWT is always an access token, as it could be an ID token or used for other purposes.

Myth 3: JWTs Are Vulnerable Because Their Payload Is Readable

As mentioned before, you can decode a JWT by using jwt.io. The following screenshot shows the content of a test JWT:

A common reaction upon seeing a JWT for the first time is alarm. "I can decode this! The data is exposed! JWT is an insecure format!"

A standard JWT is normally signed. Its payload is simply Base64Url encoded, not encrypted. You can easily paste the payload into any Base64 decoder and read its contents.

This visibility is by design. The purpose of the signature on a JWT is to guarantee integrity and authenticity, not confidentiality. The signature ensures that:

- The data has not been tampered with since it was signed.

- The token was genuinely created by the party holding the signing key.

You should never put sensitive or secret information in the payload of a JWT. If you need confidentiality, you must use JWE (JSON Web Encryption), which encrypts the payload.

Myth 4: A Signature Makes a JWT Inherently Secure

The signature is the most critical security feature of a JWT, but it's not a silver bullet. A signature is only as strong as the processes around it. Believing that "it's signed, so it's safe" is a dangerous oversimplification.

For a signed JWT to be truly secure, you must:

- Use a strong algorithm: Always use strong signing algorithms like

RS256orES256. Critically, your validation library must prevent the "none" algorithm attack, where an attacker strips the signature and changes thealgheader to"none". - Validate all relevant claims: A valid signature only proves the token hasn't been modified. It doesn't mean the token is still usable. You must always validate the standard claims:

exp: Is the token expired?nbf: Is the token being used before it's valid?iss: Was the token issued by the authority you trust?aud: Was this token intended for your service (the audience)?

- Protect your signing keys: If an attacker steals your symmetric secret (

HS256) or your private key (RS256), they can forge valid tokens for any user. Key management is paramount. - Transmit securely: Always transmit JWTs over a secure channel (HTTPS) to prevent man-in-the-middle attacks from stealing the token in transit.

A signature doesn't protect against token theft via Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) or compromised client devices. It's one piece of a larger security puzzle.

Myth 5: JWTs Are a Modern Replacement for Sessions

This is perhaps the most contentious and widely debated myth. Many tutorials present JWTs as the "modern" way to handle user sessions, replacing old-fashioned server-side sessions. This is a misleading and often harmful narrative.

Traditional server-side sessions store session data on the server and give the client a simple, opaque session ID (usually in an HttpOnly cookie). JWTs, when used for sessions, move this state to the client inside the token.

This "stateless" approach has a massive drawback for user sessions: revocation is extremely difficult.

- You can't easily log a user out: If a user clicks "log out," how do you invalidate their JWT? It remains valid until its expiration time.

- A compromised token is a lasting threat: If a JWT is stolen, the attacker can use it until it expires. You have no immediate way to kill that session.

Workarounds like blocklisting tokens exist, but they reintroduce server-side state, defeating the primary purpose of using JWTs for statelessness in the first place. At that point, you've just built a more complicated version of traditional sessions.

JWTs excel for short-lived, transactional scenarios where statelessness is a key architectural driver (e.g., authorizing a request in a microservices mesh). For managing user login state, the ability to centrally manage and instantly revoke sessions often makes the "old-fashioned" server-side session model a safer and simpler choice.

Interested in getting up-to-speed with JWTs as soon as possible?

Download the free ebook

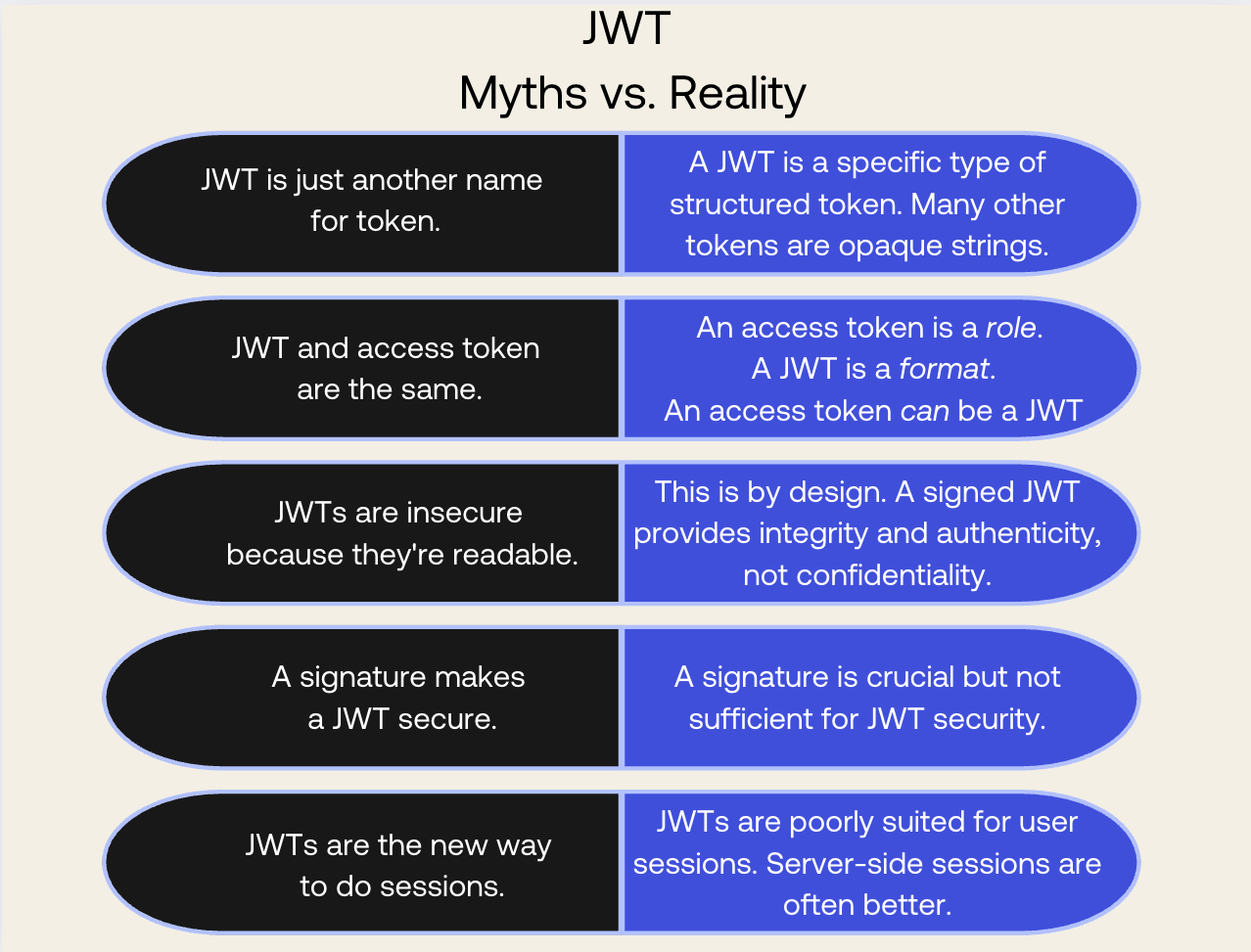

Myths at a Glance

When applied correctly, JSON Web Tokens are a powerful and useful specification. They provide a standard for creating self-contained, verifiable tokens ideal for stateless systems and inter-service communication.

However, understanding their limitations is just as important as knowing their benefits. Here is a quick recap of the myths analyzed in this article:

By moving past these common myths, you can make more informed architectural decisions. Don't treat JWTs as a generic solution for all things authentication and session-related. Instead, see them as a specialized tool in your developer toolkit—one that is incredibly effective when used for the right job.

About the author

Andrea Chiarelli

Principal Developer Advocate

I have over 20 years of experience as a software engineer and technical author. Throughout my career, I've used several programming languages and technologies for the projects I was involved in, ranging from C# to JavaScript, ASP.NET to Node.js, Angular to React, SOAP to REST APIs, etc.

In the last few years, I've been focusing on simplifying the developer experience with Identity and related topics, especially in the .NET ecosystem.