In our last post from the JavaScript for Microcontrollers and IoT series we took a look at Espruino on top of the popular ESP8266. We found Espruino awesome to work with but very limited on the ESP8266. Espruino does provide something very important on other hardware platforms: TLS support. In this post we go back to the Particle Photon to fix one of its biggest shortcomings: missing TLS support. Will we be able to add it? Read on!

“Will we be able to use a TLS library on the Particle Photon with JavaScript? Read on!”

Tweet This

Introduction

Throughout the JavaScript for Microcontrollers and IoT series we have explored different alternatives for adding JavaScript to microcontroller platforms. We have also learned how to use both C and JavaScript libraries. However, one missing part of the puzzle we have left out so far is secure communications.

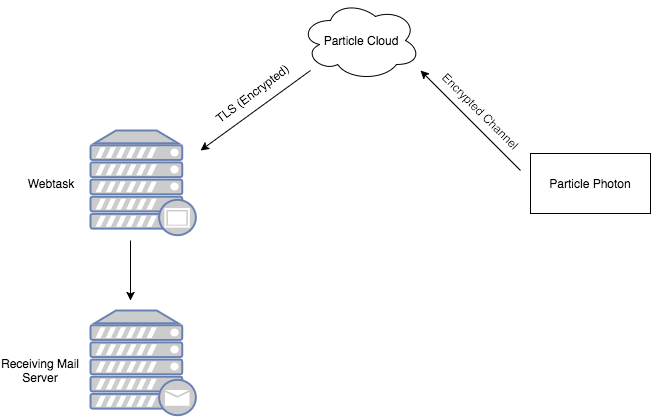

When we explored the Particle Photon as an alternative, its firmware gave us an option for secure communications: its connection to the Particle Cloud. The Particle Cloud is a series of online services provided by Particle, the developers of the Photon. This is very convenient: easy to use, encrypted, and capable of acting as a gateway to other online services. The Particle Cloud allowed us to send our sensor data to a Webtask securely. This is great! However, for some applications, relying on an external cloud platform is not an option. Furthermore, the Particle Cloud has its own limitations that may not be adequate for our purposes. We need an alternative.

On the other hand, we also looked at Espruino on the ESP8266. Espruino provides support for TLS, however, it is only enabled for certain hardware. In the case of the ESP8266 it is disabled by default. Thus Espruino and the ESP8266 are not a valid alternative for secure communications.

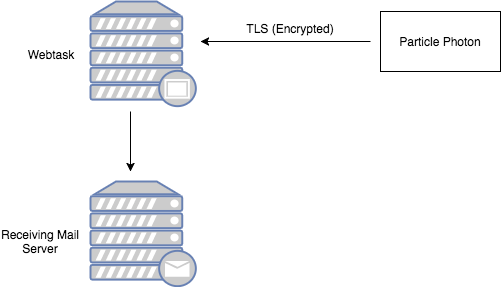

In this post we will take a look at the obvious option: adding a secure communications library to the Particle Photon. There are many alternatives for this, but we will go for what is most used on the Internet: TLS. This will allow us to communicate with common services without a gateway or proxy like the Particle Cloud in the middle.

Small TLS Libraries

TLS, and its predecessor, SSL, are quite big. There are many ciphers and algorithms supported by it. So, to keep code size and memory usage to a minimum, it is important that we pick a library that is designed with that in mind. There are three main competitors in that space: Mbed TLS (formerly known as PolarSSL), wolfSSL (formerly known as CyaSSL) and GUARD TLS (formerly MatrixSSL). All three of them are open-source and have free software licenses, however only one of them allows its use in closed-source projects without paying fees: Mbed TLS. All three are well regarded in the embedded community, so it's really up to your use case or licensing requirements which one you should pick. To keep all our options open, we chose Mbed TLS.

A Short TLS Recap

Transport Layer Security (TLS) is a standard for secure communications on computer networks. Its predecessor, Secure Sockets Layer (SSL), was developed by Netscape for its web browser in 1994. TLS is used for secure communications on the Internet and is the security layer implemented by HTTPS, which is basically HTTP over a TLS-enabled TCP/IP socket (this means almost all Internet transactions rely on TLS for security). TLS supports many different algorithms providing various levels of security and computational complexity. It also supports advanced features such as forward secrecy, which prevents the decryption of messages from the past even if keys are compromised in the future.

TLS works through a combination of asymmetric and symmetric cryptography. Asymmetric cryptography uses two keys, one public and one private, to a allow for encrypted data to flow in a single direction. The public key can be used to encrypt data that only the private key can decrypt. Symmetric cryptography, on the other hand, uses a single shared key to encrypt and decrypt data. This means that anyone who knows the shared key can read and change data encrypted with it.

TLS works by keeping a series of trusted public keys on the side of one of the peers in the form of public certificates. Certificates are information about an entity signed by that entity (or others) using its private key. Certificates also carry the entity's public key within it. The entity's public key allows anyone to check signatures performed by that entity for validity. In other words, if you have an entity's certificate you know the entity's data (such as its name) and you can perform two actions with its public key: encrypt data for it, or check the validity of any data signed by it. But to actually be certain that this means anything, you need to make sure the public key comes from the right entity. You need to trust it.

A set of trusted certificates must be present beforehand in a TLS enabled client before initiating a connection. In the case of the Internet, web browsers and operating systems bring their own set of trusted certificates when installed.

When a connection is initiated by a client, the client connects to a server and requests the server to send its public certificate and any other certificates necessary to validate its certificate. This is done in the open without any encryption in place. The client can then validate the server's certificate by looking for a signature from one of its trusted certificates (the ones preinstalled in the client). Servers usually rely on intermediate certificates for validation. This means that certificates are usually signed by certificates which are not from the trusted set. These intermediate certificates are then signed by one of the trusted certificates. So, to check the validity of a server's certificate, a client must follow the chain of certificate signatures up until it finds a signature from one of the trusted certificates. If all signatures check out, then the certificate that was received can be considered valid. For internet connections, once a server's certificate is validated, the client must compare one of the fields in it, the Common Name (CN), with the host name requested when initiating the connection. Thus, if a client wants to connect to www.google.com, the certificate must be for www.google.com (the common name in the certificate must match the address requested by the browser).

It is up to the entities that control the set of trusted certificates to make sure that whoever requests a certificate for a specific domain is the actual owner of that domain. This way, only Google (the company) can request a certificate for www.google.com.

Once a certificate is validated and the domain matches the common name, a secure communications channel can be established. For this, TLS makes use of a key-exchange algorithm. These algorithms rely on the server's certificate and asymmetric encryption to negotiate a new shared key between the server and the client. There are several different algorithms for this supported by TLS. Once this key is established the communication switches to symmetric encryption. Symmetric encryption is more efficient than asymmetric encryption and thus is more suitable for exchanging data with the server after the initial handshake. TLS supports different symmetric algorithms for this as well, but most of time one of the variants of AES is picked.

Mbed TLS

Mbed TLS is a C library. It requires a C99 compiler and is highly configurable. We will remove anything that is not necessary such as file access, old-version support (SSLv3), Berkeley/BSD/Linux sockets, etc. to keep code size to a minimum.

A Big Warning

Before going forward a big note of caution is required. Some of the algorithms required by TLS rely on a good entropy source. An entropy source is a source of randomness. This is usually used to feed the random number generator (RNG) used internally by Mbed TLS. This poses a problem: there is no good entropy source in the Particle Photon available out of the box. Note that a pseudo random number generator (PRNG) (such as the one provided by the Particle Firmware) is not good enough.

One option is to construct your own (another option), another is to buy one. Whatever you choose, be aware that not having a good entropy source may result in compromised communications. For our example we have configured Mbed TLS to use the PRNG provided by the Particle Firmware. THIS IS A BAD IDEA, DO NOT USE THIS IN PRODUCTION. Particle's PRNG relies on setting a truly random seed during boot, which is not done unless you connect to the Particle Cloud. Even then, there is no guarantee the PRNG is a good enough entropy source for cryptographic purposes. Buy a professional random number generator and integrate it in your project if you want to use something like this in production.

The Example

For our example we will turn once more to our sensor hub example. However, we will use the version from the third post and build on top of that. The sensor hub example from our third post does the following:

- It continually monitors each sensor looking for critical conditions. If a critical condition is detected, it sends an alarm event to the the Particle Cloud.

- It periodically sends a report of the sensors' current values to a local server.

For this post we will change the example to do the following:

- It will continually monitor each sensor looking for critical conditions. If a critical condition is detected, it will send a HTTP request to a Webtask.

- It will periodically send a report to the same Webtask regardless of a critical condition using a HTTP request.

Webtasks require TLS, so all HTTP requests will be encrypted.

You may have noticed that in our new example there is no mention of the Particle Cloud. That's right, having TLS allows us to stop relying on the Particle Cloud for secure communications.

Step 1: Set Up Mbed TLS

To use Mbed TLS we downloaded the latest tarball from its website and unpacked it in a directory of our choosing. We then adapted the Docker command line to expose this directory to the Docker image we use to compile our Particle Photon firmware.

Mbed TLS supports makefiles and CMake. Since we are already making use of CMake for JerryScript, we have setup Mbed TLS using CMake. Compiling MBed TLS is just a matter of calling CMake the right way. Snippet from Makefile.particle:

mbed: mkdir -p $(BUILD_DIR)/mbedtls CFLAGS="$(EXT_CFLAGS) -Os" cmake -B$(BUILD_DIR_MBED) -H../mbedtls \ -DENABLE_TESTING=OFF \ -DUSE_SHARED_MBEDTLS_LIBRARY=OFF \ -DUSE_STATIC_MBEDTLS_LIBRARY=ON \ -DENABLE_PROGRAMS=OFF \ -DCMAKE_TOOLCHAIN_FILE=$(JERRYDIR)/cmake/toolchain_external.cmake \ -DEXTERNAL_CMAKE_SYSTEM_PROCESSOR=armv7l \ -DEXTERNAL_CMAKE_C_COMPILER=arm-none-eabi-gcc \ -DEXTERNAL_CMAKE_C_COMPILER_ID=GNU make VERBOSE=1 -C$(BUILD_DIR_MBED)

We want to build a lean and clean version of Mbed TLS without any superfluous features such as file access. All Mbed TLS options are set through its config.h file. Take a look at the settings we picked for this example. TLS 1.1, RSA, Elliptic-Curve and AES are supported. Three important settings to keep RAM usage to a minimum are:

#define MBEDTLS_MPI_WINDOW_SIZE 1 #define MBEDTLS_AES_ROM_TABLES #define MBEDTLS_SSL_MAX_CONTENT_LEN 6144

The first line changes an internal setting of the big number library used by Mbed TLS. This slows down operations, but consumes less RAM. The second line tells the build system to precompile the tables that are used by the AES algorithm and to store them in a static const C array. This allows the tables to be kept in ROM rather than RAM. The third line reduces the size of the receive buffer used by Mbed TLS. TLS mandates a buffer of at least 16KiB, but it is possible to use smaller buffers when both server and client support the extension or when the data never exceeds the buffer size.

Mbed TLS's original config.h file is fully documented. Take a look at it if you are interested in tuning the library to your needs.

Step 2: Add TLS Support to Particle's TCPClient

One of the cool things about Mbed TLS is that it is very simple to use with any communications channel. The library simply requires two functions to be defined: one for writing data to the channel, and one for receiving data. Of course, if you are using a well known sockets library such as Berkeley sockets (as used by most Unixes like macOS or Linux) or WinSock (Windows sockets), Mbed TLS provides the necessary functions for you. Since we are using the Particle Photon, there is no out of the box support for our TCP client library. Fortunately, writing the send/receive functions is very simple:

TCPClient client; static int tcp_client_send(void *ctx, const unsigned char *buf, size_t len) { TCPClient *client = reinterpret_cast<TCPClient *>(ctx); return client->write(buf, len); } static int tcp_client_recv(void *ctx, unsigned char *buf, size_t len) { TCPClient *client = reinterpret_cast<TCPClient *>(ctx); const int read = client->read(buf, len); if(read <= 0) { return MBEDTLS_ERR_SSL_WANT_READ; } else { return read; } } bool connect(const char *host, uint16_t port) { // (...) mbedtls_ssl_set_bio(&ssl, &client, tcp_client_send, tcp_client_recv, NULL); // (...) }

We have written a small C++ class that uses Particle's TCPClient and Mbed TLS to connect to a server:

struct tls_tcp_client { tls_tcp_client() { mbedtls_ssl_init(&this->ssl); mbedtls_ssl_config_init(&this->conf); mbedtls_entropy_init(&this->entropy); mbedtls_ctr_drbg_init(&this->ctr_drbg); /* This is the best entropy source we have, NOT SECURE */ mbedtls_entropy_add_source(&entropy, get_random, NULL, 1, MBEDTLS_ENTROPY_SOURCE_STRONG); mbedtls_ctr_drbg_seed(&ctr_drbg, mbedtls_entropy_func, &entropy, NULL, 0); mbedtls_ssl_config_defaults(&conf, MBEDTLS_SSL_IS_CLIENT, MBEDTLS_SSL_TRANSPORT_STREAM, MBEDTLS_SSL_PRESET_DEFAULT); mbedtls_ssl_conf_rng(&conf, mbedtls_ctr_drbg_random, &ctr_drbg); mbedtls_ssl_conf_ca_chain(&conf, &global_tls_ca, NULL); mbedtls_ssl_conf_authmode(&conf, MBEDTLS_SSL_VERIFY_REQUIRED); //mbedtls_ssl_conf_verify(&conf, verify, NULL); mbedtls_ssl_conf_max_version(&conf, MBEDTLS_SSL_MAJOR_VERSION_3, MBEDTLS_SSL_MINOR_VERSION_2); mbedtls_ssl_conf_min_version(&conf, MBEDTLS_SSL_MAJOR_VERSION_3, MBEDTLS_SSL_MINOR_VERSION_2); } bool connect(const char *host, uint16_t port) { mbedtls_ssl_session_reset(&ssl); mbedtls_ssl_setup(&ssl, &conf); mbedtls_ssl_set_bio(&ssl, &client, tcp_client_send, tcp_client_recv, NULL); Log.trace("TLS connect to host: %s", host); mbedtls_ssl_set_hostname(&ssl, host); client.connect(host, port); Log.print(client.remoteIP().toString()); int code = 0; unsigned long now = millis(); while((code = mbedtls_ssl_handshake(&ssl)) == MBEDTLS_ERR_SSL_WANT_READ) { if((millis() - now) > 10000) { // timeout break; } //Log.trace("10 Free mem: %u", System.freeMemory()); Particle.process(); } if(code != 0) { char buf[128]; mbedtls_strerror(code, buf, sizeof(buf)); Log.trace("TLS connected failed, code %i -> %s", code, buf); client.stop(); return false; } return true; } // (...) }

See all the code for this class here.

Step 3: Expose Our TLS-Enabled TCPClient to JavaScript

Exposing a new version of our photon.TCPClient JavaScript object but with support for TLS is really simple as well. We only need to wrap our tls_tcp_client class using JerryScript's API. This is similar to what we did for the normal TCPClient provided by the Particle firmware.

static jerry_value_t create_tls_tcp_client(const jerry_value_t func, const jerry_value_t thiz, const jerry_value_t *args, const jerry_length_t argscount) { jerry_value_t constructed = thiz; // Construct object if new was not used to call this function { const jerry_value_t ownname = create_string("TLSTCPClient"); if(jerry_has_property(constructed, ownname)) { constructed = jerry_create_object(); } jerry_release_value(ownname); } // Backing object tls_tcp_client *client = new tls_tcp_client; static const struct { const char* name; jerry_external_handler_t handler; } funcs[] = { { "connected", tls_tcp_client_connected }, { "connect" , tls_tcp_client_connect }, { "write" , tls_tcp_client_write }, { "available", tls_tcp_client_available }, { "read" , tls_tcp_client_read }, { "stop" , tls_tcp_client_stop } }; for(const auto& f: funcs) { const jerry_value_t name = create_string(f.name); const jerry_value_t func = jerry_create_external_function(f.handler); jerry_set_property(constructed, name, func); jerry_release_value(func); jerry_release_value(name); } jerry_set_object_native_pointer(constructed, client, &tls_client_native_info); return constructed; }

Here we create a new tls_tcp_client object and set it as the backing object of a new instance of our photon.TLSTCPClient object. To see the rest of the wrapper functions, see the tlstcpclient.h file.

We also expose a function that allows us to globally add new trusted certificates. These are the certificates that TLS clients must know beforehand to verify the certificates sent by servers.

static jerry_value_t tls_tcp_client_add_certificates(const jerry_value_t func, const jerry_value_t thiz, const jerry_value_t *args, const jerry_length_t argscount) { if(argscount != 1 || !jerry_value_is_string(*args)) { return jerry_create_error(JERRY_ERROR_TYPE, reinterpret_cast<const jerry_char_t *>( "Expected certificate as string")); } const size_t size = jerry_get_string_size(*args); std::vector<char> buf(size + 1); jerry_string_to_char_buffer(*args, reinterpret_cast<jerry_char_t*>(buf.data()), buf.size()); int code = 0; if((code = mbedtls_x509_crt_parse(&global_tls_ca, reinterpret_cast<unsigned char *>(buf.data()), buf.size())) != 0) { Log.trace("Failed to parse certificate: %i", code); Log.trace("%s", buf.data()); return jerry_create_error(JERRY_ERROR_TYPE, reinterpret_cast<const jerry_char_t *>( "Failed to parse certificate")); } return jerry_create_undefined(); }

Step 4: Change The JavaScript code

Adapting our JavaScript sensor hub code is quite simple. We only need to change the uses of photon.TCPClient to photon.TLSTCPClient and make sure we set the right trusted certificates before connecting to a server. We also need to update the URL we are using to send the data.

function buildHttpRequest(data) { const request = `POST ${path} HTTP/1.1\r\n` + `Host: ${host}\r\n` + `Content-Length: ${data.length}\r\n` + `Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded\r\n` + `Secret: ${secret}\r\n` + 'Connection: close\r\n\r\n' + data; return request; } function sendData(data) { const client = photon.TLSTCPClient(); client.connect(host, port); if(!client.connected()) { photon.log.error(`Could not connect to ${host}:${port}, ` + `discarding data.`); return; } client.write(buildHttpRequest(data)); client.stop(); }

Since we are going to reuse the Webtask we prepared for our original sensor hub example (i.e. we are not going to make any changes to the Webtask at all), we need to send the data using the exact same format that was used by the Particle Cloud. Fortunately this is very simple.

The data was sent as a POST HTTP request carrying a special header named Secret and containing a plain-text secret that the server must verify. The data was sent as part of the POST request body using URL encoding and the following keys:

coreid: a string with the ID of the Particle Photon sending the data.event: a string with the event being sent. Eithersensor-dataorsensor-event.data: a string with the sensor data. This is a stringified JSON object.

function objectUrlEncode(obj) { var str = []; for(let p in obj) { if(obj.hasOwnProperty(p)) { const key = encodeURIComponent(p); const val = encodeURIComponent(obj[p]); str.push(key + "=" + val); } } return str.join("&"); } function sendEvent(event, data) { try { const datastr = JSON.stringify(data); photon.log.trace(`Sending event ${event}, data: ${datastr}`); try { // Send event to our server sendData(objectUrlEncode({ event: event, data: datastr, coreid: coreid })); } catch(e) { photon.log.error(`Could not send event to server: ${e.toString()}`); } // Send event to Particle cloud: disabled to reduce memory usage // photon.publish(event, datastr); } catch(e) { photon.log.error(`Could not publish event: ${e.toString()}`); } }

This code is located in the js subfolder of the example directory. You will need to update the code to send the right data for your Webtask (i.e. update the Secret, the coreid and the URL for your Webtask).

That's it! With all of these changes in place, we can now test our new TLS-enabled sensor hub.

Step 5: Try It Out!

We are going to report to the same Webtask we used for previous posts, so it is not necessary to redeploy our Webtask. If you want to learn how to deploy a Webtask, check the second post. To flash the Particle Photon on Linux put the Photon in DFU mode and then run the following script:

./compile-and-flash.sh

If you are on a different platform, check the first post to learn about the different ways of flashing the Particle Photon.

About Auth0

Auth0 by Okta takes a modern approach to customer identity and enables organizations to provide secure access to any application, for any user. Auth0 is a highly customizable platform that is as simple as development teams want, and as flexible as they need. Safeguarding billions of login transactions each month, Auth0 delivers convenience, privacy, and security so customers can focus on innovation. For more information, visit https://auth0.com.

Conclusion

We have pushed the Particle Photon to its limits. We integrated a JavaScript interpreter plus a TLS library and had them play together. We filled up all usable ROM and RAM and, luckily, it worked! However, we cannot recommend going this route for production. We had to microtune memory use to make sure everything worked together. Either go for a bigger microcontroller, or forego one element: JavaScript or TLS. We think it would be a good idea for Particle developers to expose the Mbed TLS library embedded in the firmware so that user applications could link against it. Having two copies of the same library in a memory limited device is wasteful.

We are also very interested in seeing how Espruino behaves for TLS use on validated hardware, but, sadly, we don't have any in our power for now. If you choose to use Mbed TLS on the Particle Photon don't forget to get a hardware random number generator, not having one defeats the purpose of using TLS in the first place! As we have seen, once TLS is available, microcontrollers become much more powerful, and a whole host of preexisting services, like Webtasks, become immediately available.

“Once TLS is available, microcontrollers can take advantage of preexisting services, like Webtasks”

Tweet This

This concludes our JavaScript for Microcontrollers and IoT series for now. If you would like us to explore something else in relation to IoT, let us know in the comments. Hack on!

About the author

Sebastian Peyrott

Senior Engineer