Concretely, ListObjects answers questions like: “given a user and a relation, which objects of a particular type does that user have that relation to?” For example: “which object resources does user:alice have viewer on?”

Unlike a boolean check (“does Alice have access to this one object?”), ListObjects is an enumeration: it computes a set of matching object IDs by evaluating your authorization model against the relationship tuples stored in your datastore.

If you've ever shipped an app with real authorization requirements, you've felt the tension:

- You want ListObjects behavior everywhere: "show me all documents I can view", "which projects can this service account access", "list all resources shared with this user".

- You also need predictable latency and bounded resource usage under wildly different data distributions.

In OpenFGA (the open-source engine that powers Auth0 FGA), ListObjects is fundamentally a graph traversal problem over relationship tuples. This post is a guided tour of the pipeline traversal approach: how it builds a worker pipeline from the authorization model graph, how messages flow through it, and which tuning knobs matter when you're chasing tail latency.

Why ListObjects is hard (and why it matters)

Authorization is on the critical path of nearly every request, and tail latency (P95/P99) is what users actually feel. For ListObjects, you're not just proving a single relationship, you are enumerating potentially many objects, and doing it fast enough to sit on the hot path of an API.

Two forces dominate performance:

- The "shape" of your authorization model (amount and position of operators, rewrites, and cycles).

- The tuple distribution (cardinality, ie how many tuples exist for the relations you query, fanout, ie how many results each lookup tends to return, skew, ie how uneven that distribution is across users/objects) and the datastore latency profile underneath (your storage layer’s real-world query behavior—P50/P95/P99 latency, variance under load, and how it responds to the specific query shapes ListObjects generates).

The mental model: a weighted graph

OpenFGA models can be represented as a weighted directed graph (potentially cyclic). Nodes represent types/relations and operator nodes (like union/intersection/exclusion), and edges represent how nodes connect.

At a high level, the pipeline traversal is a pub/sub connection of workers that pass messages along the ListObjects path in the model graph in order to resolve a ListObjects query. It uses the weighted graph to build a pipeline of workers connected by edges.

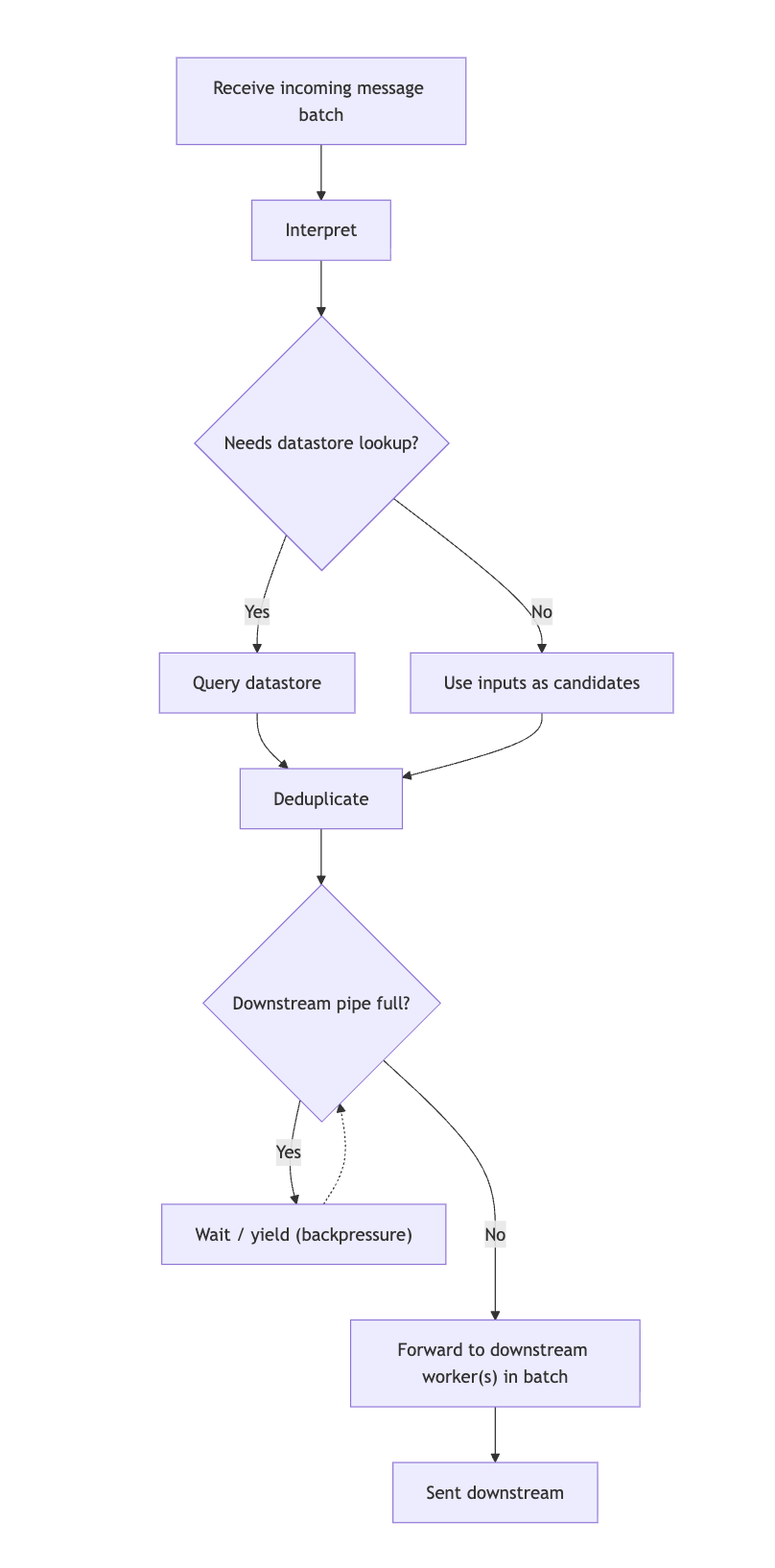

Each worker is responsible for a small, repeatable slice of the overall traversal:

- Receive a message from one of its inputs (its subscribed senders).

- Interpret that message in the context of a specific node/edge in the model graph (e.g., “apply

and/or/but notsemantics”). - Query the datastore when needed to turn input users into objects that can be passed as candidates to the next worker.

- Deduplicate and batch intermediate results to avoid redundant work and reduce per-item overhead.

- Forward the resulting messages to downstream workers through its output pipes, yielding to back pressure when those pipes are full.

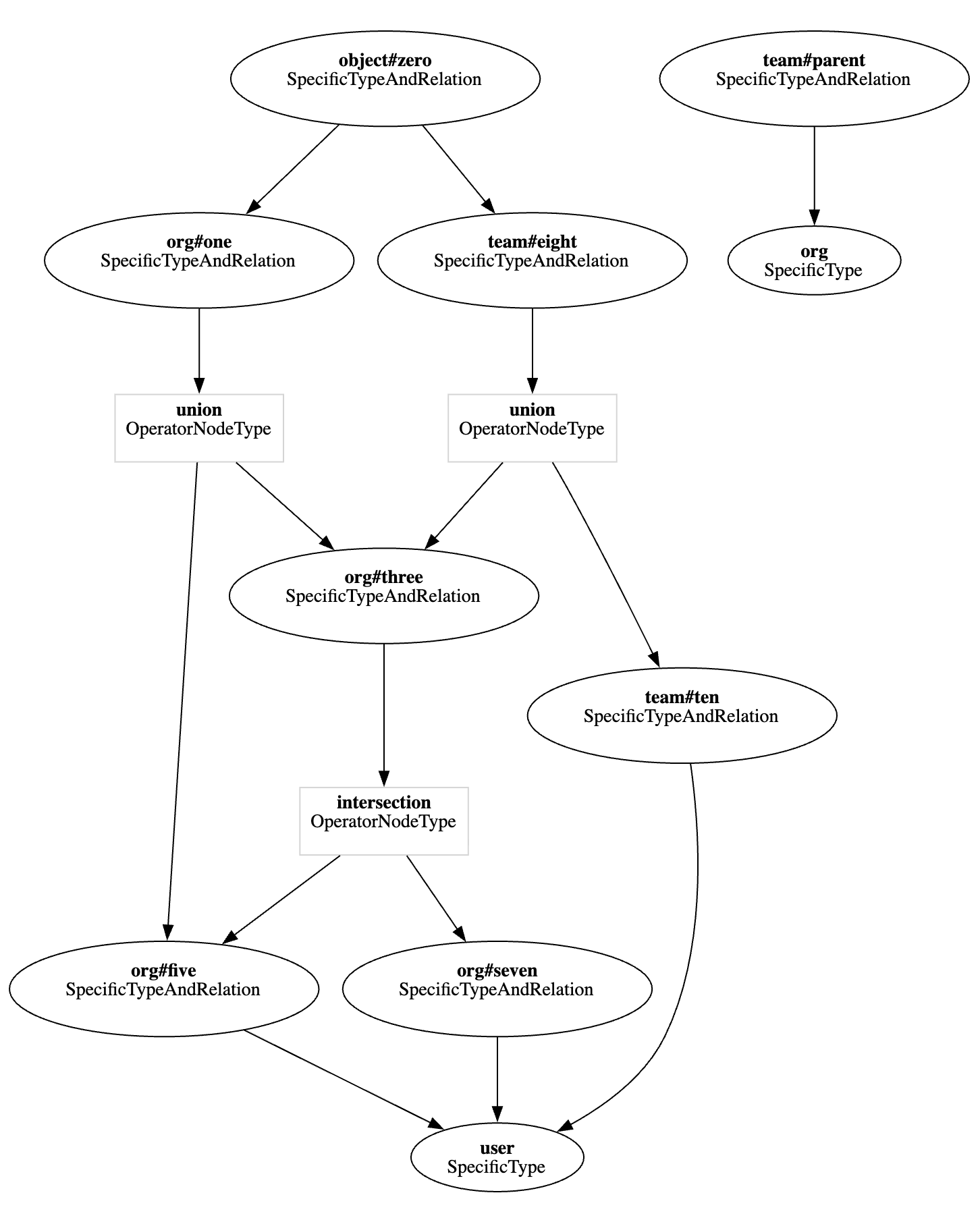

Here's a small example authorization model:

model schema 1.1 type user type org relations define five: [user] define seven: [user] define three: five and seven define one: three or five type team relations define ten: [user] define eight: ten or three from parent define parent: [org] type object relations define zero: [org#one, team#eight]

This model can be visualized as a graph with relations as nodes that connect through edges:

As the pipeline builder traverses the graph, for this example, it builds the workers in the same numerical order as the relation names in the graph (for example: object#zero, org#one, etc.).

From Graph to Pipeline: Building Workers With DFS

The pipeline is built by traversing the weighted graph in a Depth-first Search (DFS) starting at the source (the object type + relation you're listing) and connecting back toward the target (the user/userset you're listing for). Conceptually, the traversal creates a worker for each node it needs, it backtracks when a node has no more unexplored edges, and it avoids re-traversing nodes that were already visited (workers store pointers to graph nodes).

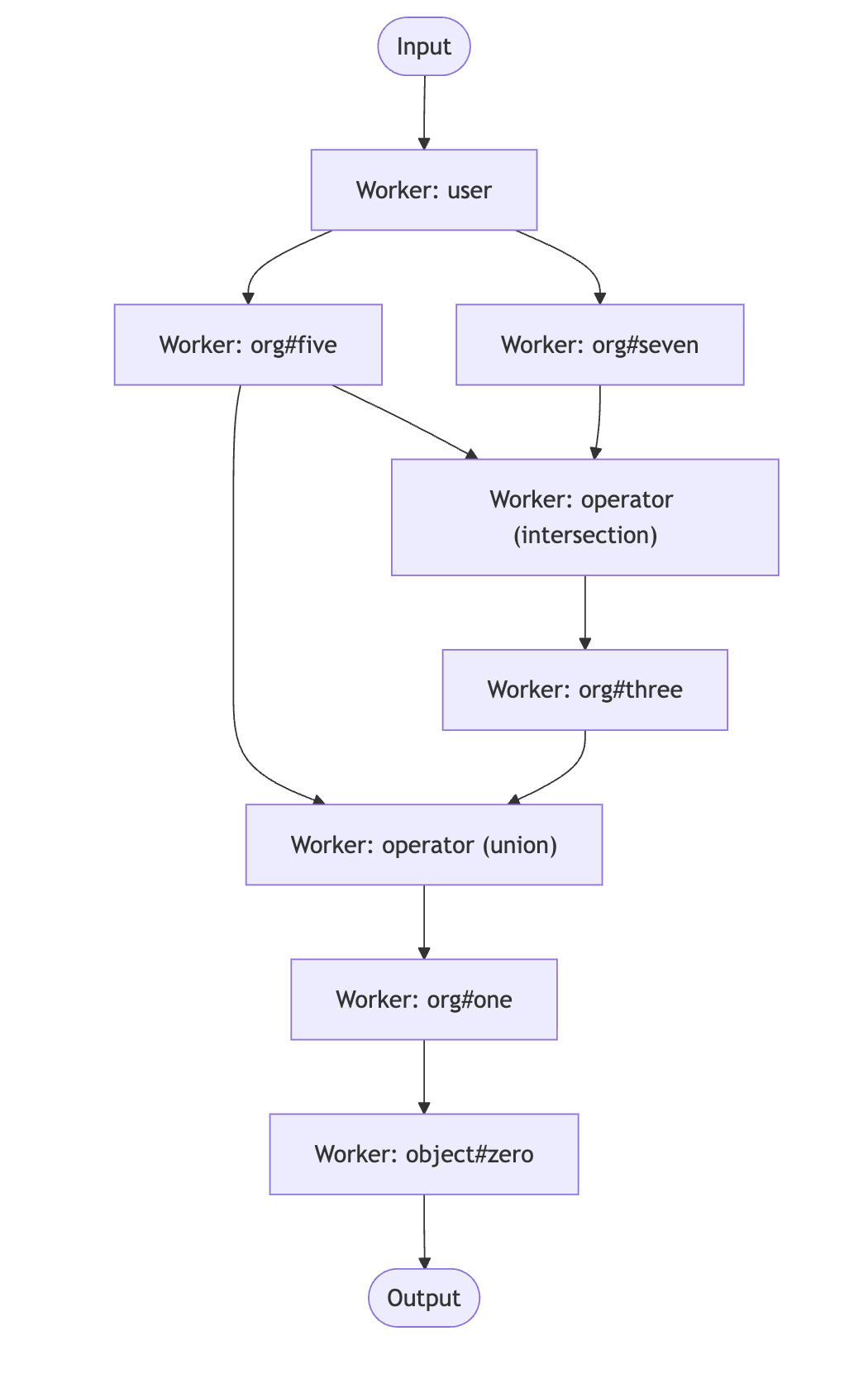

For this model, imagine a ListObjects query like:

{ "object": "object", "relation": "zero", "user": "user:anne" }

When the pipeline is constructed, it seeds an initial message into the worker whose type matches the target. For example, if the target is user:anne, the user worker receives that message to kick off processing, which it then sends to any workers subscribed to it.

From there, any worker that is subscribed to the user worker receives user:anne and starts querying in the datastore to find objects that relate to that user (e.g., if the relation is org#five the datastore will query for any objects on that relation for user user:01ARZ...). Workers batch results into messages of size up to chunkSize, so upstream workers can process objects in batches. Any objects found will then be sent to workers subscribe to org#five, like the union and intersection. Messages continue to be sent through the pipeline and queried for objects in the datastore until they reach the source worker.

When messages reach the source worker (the type+relation you're listing), the pipeline emits results into the output stream.

If you're trying to understand how the pipeline is wired, it can be clearer to look at it as a pub/sub graph.

The arrows below show message flow (publisher → subscriber).

Workers remain open as long as their senders might still produce messages. After completion, the pipeline waits for all worker goroutines to finish, then cancels contexts and closes listeners.

Closing listeners uses a broadcast-style mechanism to: mark pipes as done, wake goroutines blocked on reads/writes, and allow the pipeline to terminate cleanly.

Special Cases You Must Handle in Real Use Cases

Authorization graphs aren't neat trees. The pipeline includes special handling for the common "hard edges."

Intersection and Exclusion

Intersection (and) and exclusion (but not) have a fundamental requirement: you can't decide the output until you have enough information from both sides.

- For intersection, evaluation blocks until all messages from both sides are processed, then it compares the object sets, removes duplicates, and forwards only the objects that appear in both.

- For exclusion, the pipeline stages the "include" stream and blocks on the "exclude" side. As soon as the exclude side completes, the pipeline drains the staged include stream and filters out excluded objects.

That exclusion optimization matters in practice: it reduces how long upstream workers wait before they can resume work.

Tuple-to-userset (TTU)

Tuple-to-userset edges require a rewrite: the "object relation" you just found must be converted into the "tupleset relation" before the next lookup.

In the earlier model:

type team relations define ten: [user] define eight: ten or three from parent define parent: [org]

If you find an org:b object that matches org#three, the next step is to look for team objects whose parent is that org. That changes the next datastore query shape (and, often, its cardinality).

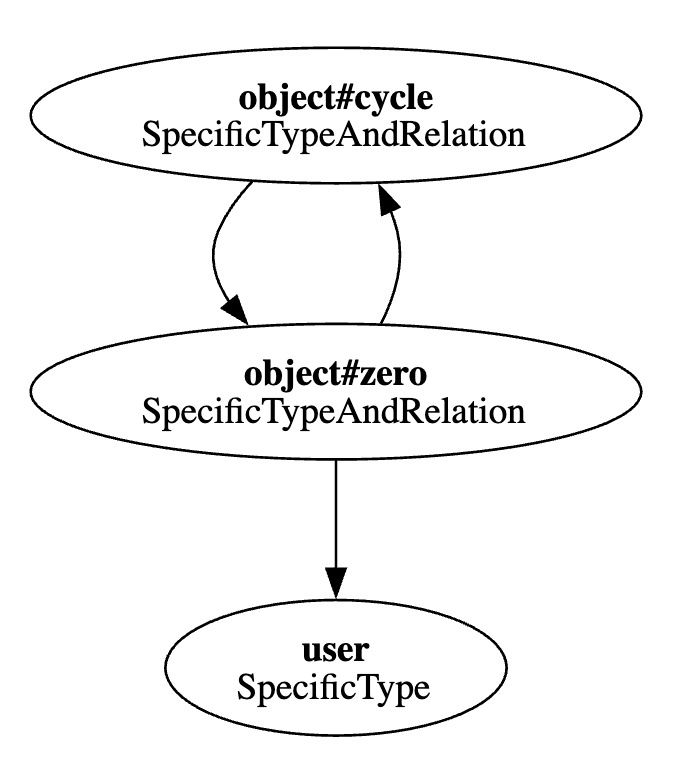

Cycles

Cycles are where naive traversals can get stuck: without safeguards, messages can circulate indefinitely.

Here's a small cycle model:

model schema 1.1 type user type object relations define cycle: [object#zero] define zero: [user, object#cycle]

This model may include the following tuples which create a cycle:

[{ "object": "object:1#zero", "relation": "cycle", "user": "object:1" }, { "object": "object:1#cycle", "relation": "zero", "user": "object:1" }]

For cycles, the pipeline has some reasoning to avoid infinite loops and handle termination:

- Input deduplication: a shared input buffer avoids re-processing the same items as they circulate.

- Shared message tracking and status: cyclic edges share tracking so the entire cycle can agree on "no messages in flight".

- A separate processing queue and termination logic: termination waits for all workers to report that non-cyclical work is done and that in-flight messages have drained.

Performance Tuning: The Knobs That Matter

The pipeline exposes a small set of configuration settings that trade off throughput, memory, and contention, which can be set when used as a library. These are intentionally low-level: the right values depend on your tuple distribution and datastore latency profile.

numProcs limits how many messages are processed concurrently per sender when querying the datastore.

- Higher values increase parallelism, but can increase contention and datastore pressure.

- Lower values reduce contention, but can underutilize CPU and increase end-to-end latency.

bufferSize caps how many messages a sender can queue to its listeners.

- Larger buffers reduce blocking and smooth out bursts.

- Smaller buffers enforce backpressure sooner (often safer) but can expose bottlenecks.

Implementation note: the buffer is a circular ring buffer and must be a power of 2.

chunkSize controls how many objects are packed into each message.

- Larger chunks reduce per-query overhead (fewer queries) but increase per-message memory.

- Smaller chunks reduce memory and improve responsiveness but may increase query overhead.

Dynamic pipe extension: reducing deadlocks under skew

Two optional settings let pipes grow dynamically when downstream work is slower than upstream sending:

ExtendAfter: extend this only if a sender blocks longer than this duration.MaxExtensions: caps how many times a pipe can double.

This can be useful for bursty workloads or highly uneven branches (e.g., one side of an intersection is much slower), but it can also increase memory usage because multiple edges may grow.

Closing Thoughts

The pipeline traversal is designed to make ListObjects fast and predictable: it streams results, limits concurrency, and uses backpressure to avoid runaway fanout when the graph (or the datastore) gets expensive.

If you're tuning performance, focus on the parts that most directly affect throughput and tail latency:

numProcscontrols how hard you push the datastore.bufferSizeand optional pipe extension control where backpressure builds.chunkSizecontrols the trade-off between batching efficiency and per-message memory.

Then test with real tuple distributions. The same model can behave very differently depending on fanout and skew, and the pipeline's configuration is deliberately low-level so you can adapt to those realities.

About the author

Victoria Johns

Software Engineer II