Python has evolved from a simple language, almost an alternative to Linux Bash, to one of the most used programming languages in the world. It dominates fields ranging from data science and machine learning to high-scale web applications. With the rise of microservice architectures, the industry needed a framework that combined Python’s simplicity with the performance required for scalable modern systems.

FastAPI emerged to fill this gap, quickly becoming the de facto standard for building REST APIs in Python. Its popularity stems from a low learning curve and powerful features like automatic data validation and documentation, which allow developers to move from idea to prototype rapidly.

However, there is a significant difference between a working prototype and a maintainable system. In this article, we will go beyond the basics and explore the architectural patterns and best practices required to build production-ready FastAPI applications.

Prerequisites

If this is your first time using the framework, I recommend starting with the Official Documentation Quickstart. For a more advanced security example, you can also check out Build and Secure a FastAPI Server With Auth0.

Design REST APIs Using the Correct Verbs and Patterns

The first principle is not exclusive to FastAPI but applies to any well-designed REST API. These APIs follow common patterns that make them easier for developers to understand and use. Also, remember that the entire API should remain consistent: if you decide on a specific way to describe your resources, stick with it throughout.

Use the Correct HTTP Verbs

The HTTP protocol defines a set of methods (often called verbs) that describe the action performed on a given endpoint. The same endpoint can accept multiple verbs, each with a distinct meaning.

| Verb | Purpose |

|---|---|

| GET | Read data |

| POST | Create a new resource |

| PUT | Full update (replace resource) |

| PATCH | Partial update |

| DELETE | Remove resource |

| HEAD | Same as GET, but returns only headers |

| OPTIONS | Describe available operations or capabilities |

What can you do with these verbs?

Imagine you have a Zoo API and want to expose a list of animals. One way to do this is by sending a GET request to the /animals endpoint. Here’s what each verb could do in this context:

GET /animals: Retrieve the list of animalsPOST /animals: Create a new animalGET /animals/{id}: Retrieve a specific animal’s dataPUT /animals/{id}: Replace all data for a specific animalPATCH /animals/{id}: Update only some fields of a specific animalDELETE /animals/{id}: Delete a specific animalHEAD /animals: Retrieve only headers about the animal list. You might use this to check metadata such as when the catalog was last updated or how many animals are listed — all without downloading the entire dataset.OPTIONS /animals: Retrieve information about what operations are available. For example, you might use it to learn how many animals can be fetched at once or which query filters (e.g., by species) are supported.

Naming Conventions

Naming conventions help readers understand your API even without reading the full documentation. Your API should be intuitive enough that any developer can explore it and understand how it works with minimal effort. Here are some tips:

- Use plural nouns for collections (

/animals,/users,/orders) - Use singular nouns for individual resources (

/animal,/user,/order) - Keep the resource hierarchy logical (

/animals/1/orders) - Use lowercase for resource names

One idea that really helped me in the past was understanding that each URL acts as a primary key for a resource on the internet. Once you create an endpoint, it should be clear what it represents, and its interface (the URL and method) should remain immutable since other applications might rely on it.

Versioning

If a system is being used, it will eventually receive updates. These updates should always consider your current users. When you need to introduce a breaking change, create a new version of your API and maintain the old one for a transition period. Make sure to clearly document the migration steps and specify the deprecation date for the previous version.

A common approach is to include the version number in the URL, such as /v1/animals.

Folder Structure

When designing a FastAPI application, one of the first architectural decisions you’ll face is how to organize your code. Your folder structure determines how easily your project can grow, how clearly new developers can navigate it, and how maintainable it will be over time.

A clean and flexible structure recommended by the FastAPI community is shown below, using our Zoo example:

app

├── alembic

├── api

│ ├── routes

│ │ ├── animal.py

│ │ └── zookeeper.py

│ └── deps.py

│ └── main.py

├── core

│ ├── config.py

│ └── security.py

│ └── db.py

├── crud.py

├── main.py

├── models.py

├── utils.py

tests

├── api

│ └── test_animals.py

└── utils.py

This structure separates the application into functional layers that are easy to understand and extend:

app/: contains all the application logic. This is the main application module.app/alembic/: contains all alembic migration files. Alembic is a tool to version your database schemas.app/api/: will have all the code related to routes, HTTP Authentication and HTTP Filtersapp/core/: contains all major system-level code. For example, configuration variables and database connectionsapp/crud/: in this example, is a simple file. But as it grows you can create a folder with different and more specific filesapp/main/: Contains the FastAPI startup codeapp/modules/: Similar to the CRUD file, this can be configured as a module with several files. Contains all database classes. Usually, these model classes are described in SQLAlchemy ORM librarytests/: contains all test files for your project. The test folder will not be attached to the production code.

This layout makes it easy for new developers to find what they need and is ideal for small to medium projects. It scales moderately well and keeps related files conceptually grouped by layer.

Note for very large projects

If your application grows into multiple business domains — such as animals, zookeepers, and habitats — consider adopting a domain-driven structure, where each domain has its own router.py, schemas.py, and models.py. This approach improves modularity and makes it easier to evolve or test individual parts of the system independently.

Strong Typing and Data Validation with Pydantic

One of FastAPI’s most powerful features is its deep integration with Pydantic. Pydantic provides runtime type validation and data parsing based on Python type hints, ensuring that your API both receives and returns correctly formatted data.

Take the following classes as an example:

class Species(enum.StrEnum): lion = "lion" tiger = "tiger" elephant = "elephant" monkey = "monkey" zebra = "zebra" panda = "panda" class Animal(BaseModel): id: uuid.UUID name: str = Field(..., min_length=5) date_of_birth: date species: Species nickname: str | None = None @field_validator("date_of_birth") @classmethod def validate_date_of_birth(cls, v): if v > date.today(): raise ValueError("Date of birth cannot be in the future") return v

And these endpoints:

@app.get("/animals/{animal_id}") def get_animal(animal_id: uuid.UUID): ... @app.post("/animals") def create_animal(animal: Animal): ...

Because your FastAPI endpoints use Pydantic models, all validation rules are enforced automatically by the framework before reaching your code. Moreover, FastAPI automatically generates detailed error responses with all the information needed to correct invalid input.

It is worth noting that StrEnum was introduced in Python 3.11 and the decorator @fiel_validator is part of Pydantic v2. Now try sending this request:

curl -X POST http://127.0.0.1:8000/animals -H "Content-Type: application/json" -d '{ "id": "1", "name": "Jose", "date_of_birth": "2020-10-01", "species": "lion" }' > {"detail":[{"type":"uuid_parsing","loc":["body","id"],"msg":"Input should be a valid UUID, invalid length: expected length 32 for simple format, found 1","input":"1","ctx":{"error":"invalid length: expected length 32 for simple format, found 1"}},{"type":"string_too_short","loc":["body","name"],"msg":"String should have at least 5 characters","input":"Jose","ctx":{"min_length":5}}]}

As you can see, FastAPI responds with a 400 Bad Request and a structured error message describing exactly what went wrong. In this case, the id field isn’t a valid UUID, and the name field is too short.

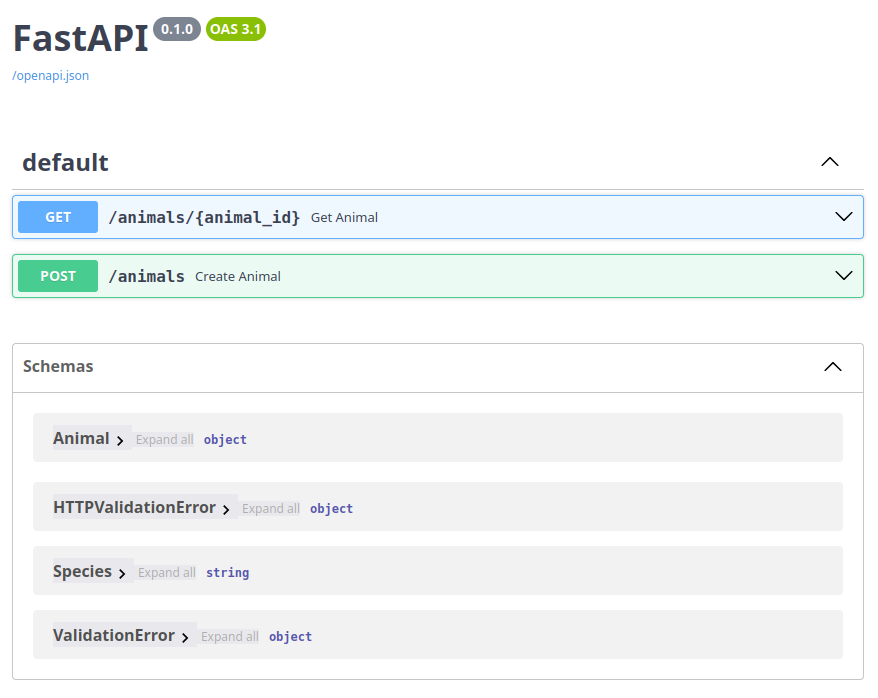

Auto OpenAPI Documentation

When using Pydantic models, FastAPI automatically generates OpenAPI documentation for your application. OpenAPI is a standard for describing RESTful APIs. It’s widely adopted by many tools to generate documentation and is also used by Swagger UI to create an interactive interface for your API.

With the application running, you can access the generated documentation at:

http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs

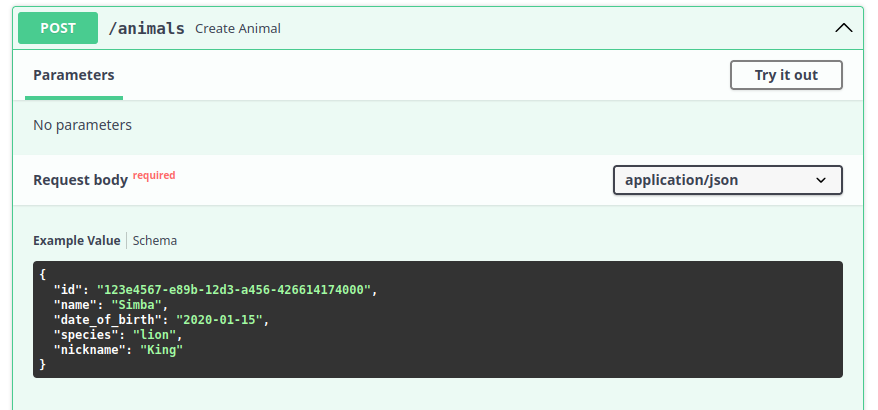

You can further enhance your Pydantic models with examples, which will appear directly in the documentation. For example:

class Animal(BaseModel): id: uuid.UUID = Field( examples=["123e4567-e89b-12d3-a456-426614174000"] ) name: str = Field( ..., min_length=5, examples=["Simba", "Leo the Lion"] ) date_of_birth: date = Field( examples=["2020-01-15"] ) species: Species = Field( examples=["lion"] ) nickname: str | None = Field( default=None, examples=["King", "Fluffy"] ) @field_validator('date_of_birth') @classmethod def validate_date_of_birth(cls, v): if v > date.today(): raise ValueError("Date of birth cannot be in the future") return v

Now, if you reload your documentation, you’ll see the examples directly in the generated UI:

Concurrency and Asynchronous Code

FastAPI natively supports both asynchronous and synchronous code. To make an endpoint asynchronous, simply add the async keyword:

@app.get("/animals/{animal_id}") async def get_animal(animal_id: uuid.UUID): ... @app.post("/animals") def create_animal(animal: Animal): ...

This will not change your application’s behavior: documentation, validation, and schema generation will continue to work exactly the same.

However, when working with asynchronous libraries, you must use the async keyword and the corresponding await keyword correctly.

It might be tempting to make everything async, but there are important considerations to keep in mind.

Understanding Async in Python (and in most Programming Languages)

Asynchronous code is designed for I/O-bound operations such as database queries, HTTP requests, or file reads/writes. Python’s async implementation uses an event loop that runs on a single thread. When you use await, the event loop can switch to other tasks while waiting for the I/O operation to complete, improving efficiency without creating multiple threads.

In contrast, synchronous code blocks the thread until the operation finishes. Even if the CPU is idle waiting for I/O, no other work can proceed in that thread.

The main risk of using async everywhere is interacting with blocking libraries. Since the event loop runs on a single thread, any blocking call will block the entire event loop, freezing your entire application.

For more details, FastAPI has beautiful detailed documentation about async development.

Dependency Injection

FastAPI is designed to handle complex applications gracefully. In larger systems, applying architectural patterns helps keep your code maintainable, testable, and modular. One of the most important of these patterns is Dependency Injection (DI) and, once you understand it, you’ll likely want to use it everywhere.

Dependency Injection, also known as inversion of control, is a design pattern that decouples components of your application. Each module is responsible for its own logic but may depend on other modules to perform its tasks. These modules should be atomic, replaceable, and independent.

For example, imagine the Animal module needs access to a database and some configuration.

Instead of doing this:

class AnimalDB: def get_animal(self, animal_id: uuid.UUID) -> Animal | None: ... animal_db = AnimalDB() @app.get("/animals/{animal_id}") async def get_animal(animal_id: uuid.UUID): return await animal_db.get_animal(animal_id)

You should do this:

class AnimalDB: def __init__(self, pool: AsyncConnectionPool): self.pool = pool def get_animal(self, animal_id: uuid.UUID) -> Animal | None: ... def get_animal_db(pool: AsyncConnectionPool = Depends(get_pool)) -> AnimalDB: return AnimalDB(pool) @app.get("/animals/{animal_id}") async def get_animal(animal_id: uuid.UUID, animal_db: AnimalDB = Depends(get_animal_db)): return await animal_db.get_animal(animal_id)

In the second example, the AnimalDB instance is injected into the endpoint via FastAPI’s dependency system, rather than being a global variable. This makes it easy to swap implementations: you could replace AnimalDB with a mock during testing without changing your production code. It also promotes cleaner architecture by removing hidden dependencies.

FastAPI’s dependency injection system is quite flexible and even supports recursive dependencies. For instance, if your AnimalDB requires a database connection pool, you can inject it as well:

class AnimalDB: def __init__(self, pool: AsyncConnectionPool = Depends(get_pool)): self.pool = pool

You can learn more about dependency injection in the official documentation.

Testing

There are at least two main approaches to testing your FastAPI application: unit testing and integration testing. The general recommendation is to use unit tests for most scenarios and reserve integration tests for complex cases that depend on multiple modules or external systems.

Let's look at both approaches.

Unit Testing

Most of your tests should fall into this category, and unit testing in FastAPI benefits greatly from Dependency Injection. When your code relies on global or external variables, tests become harder to write and maintain.

However, if your code is isolated and uses injected dependencies, you can easily mock external resources and keep your tests fast and stable.

Here’s an example:

async def test_get_animal(): mock_animal_db = Mock(spec=AnimalDB) expected_animal = Animal( id=uuid.UUID("123e4567-e89b-12d3-a456-426614174000"), name="Simba", date_of_birth="2020-01-15", species="lion", nickname="Simba the Lion" ) mock_animal_db.get_animal.return_value = AsyncMock(return_value=expected_animal) returned_animal = await get_animal(expected_animal.id, animal_db=mock_animal_db) assert returned_animal.id == expected_animal.id assert returned_animal.name == expected_animal.name

In this test, we mock the AnimalDB class and define a specific return value. The get_animal function is tested without connecting to a real database, avoiding the need for test data setup. This keeps tests extremely fast (milliseconds instead of seconds) and more reliable since they don’t depend on external systems.

Integration Testing

For integration tests, you’ll need a few additional dependencies:

- pytest

- pytest-cov

- httpx

Next, you can create a test client, which is a lightweight HTTP client provided by FastAPI for testing endpoints:

from fastapi.testclient import TestClient from app.main import app client = TestClient(app) def test_get_animals(): response = client.get("/animals") assert response.status_code == 200 assert isinstance(response.json(), list) def test_create_animal(): animal_data = { "id": "123e4567-e89b-12d3-a456-426614174000", "name": "Simba", "date_of_birth": "2020-01-15", "species": "lion" } response = client.post("/animals", json=animal_data) assert response.status_code == 201 assert response.json()["name"] == "Simba"

The code above spins up a FastAPI application instance that you can send requests to and verify the responses. You can also use Pytest fixtures to handle setup and teardown logic:

# conftest.py import pytest from fastapi.testclient import TestClient from app.main import app @pytest.fixture def client(): return TestClient(app) @pytest.fixture def sample_animal(): return { "name": "Test Lion", "date_of_birth": "2020-01-01", "species": "lion" } # test_animals.py def test_create_animal(client, sample_animal): response = client.post("/animals", json=sample_animal) assert response.status_code == 201

Even in integration tests, you can mock or override dependencies to simulate different environments or behaviors:

from app.main import app from app.dependencies import get_database def get_test_database(): # Return a test database connection return TestDatabase() app.dependency_overrides[get_database] = get_test_database def test_with_mocked_db(client): response = client.get("/animals") # This will use the test database assert response.status_code == 200

Using app.dependency_overrides, you can override any dependency at runtime and test how your application behaves under different conditions.

Error Handling

FastAPI makes it easy to decouple error handling from your application logic. Instead of scattering try/except blocks everywhere to handle every possible failure, you can define generic exception handlers.

FastAPI provides an HTTPException class that you can use for any HTTP-related error. However, should you really raise an HTTPException inside your application or database layers? Those layers shouldn’t need to know how HTTP errors are represented. Instead, you should raise domain-specific exceptions that describe what went wrong, and let FastAPI handle how those errors are returned to the client.

For example:

class ZooException(Exception): ... class AnimalNotFoundError(ZooException): ... class AnimalAlreadyExistsError(ZooException): ...

Here, ZooException is a base exception for all domain errors, while the specific ones convey precise meaning.

Now you can define custom handlers for them at the FastAPI layer:

app = FastAPI() @app.exception_handler(AnimalNotFoundError) async def animal_not_found_exception_handler(request: Request, exc: AnimalNotFoundError): return JSONResponse( status_code=404, content={"message": f"Animal not found"}, ) @app.exception_handler(AnimalAlreadyExistsError) async def animal_already_exists_exception_handler(request: Request, exc: AnimalAlreadyExistsError): return JSONResponse( status_code=409, content={"message": f"Could not create the animal. It already exists"}, )

Your business logic doesn’t need to catch these exceptions — they’ll bubble up to FastAPI, which will delegate them to the appropriate handler.

Unfortunately, FastAPI doesn’t automatically document handled exceptions in the OpenAPI schema. If you want them to appear in your docs, you need to add them manually to each endpoint:

@app.get("/animals/{animal_id}", responses={ 404: { "description": "Animal not found", "content": { "application/json": { "example": {"message": "Animal not found"} } } } } ) async def get_animal(animal_id: uuid.UUID) -> Animal: ... @app.post("/animals", responses={ 409: { "description": "Animal already exists", "content": { "application/json": { "example": {"message": "Could not create the animal. It already exists"} } } } } ) async def create_animal(animal: Animal): ...

Help Your FastAPI Journey By Understanding Key Patterns Early

Throughout this article, we've explored the best practices for building production-ready FastAPI applications. From RESTful API design principles to advanced patterns like dependency injection and custom error handling, these practices are heavily based on real-world, production-grade applications that need to scale and be maintained over time.

However, it's important to recognize that not all of these practices are suitable for small applications or quick prototypes. If you're building a simple microservice with a handful of endpoints, you probably don't need domain-driven folder structures or elaborate exception hierarchies. Start simple and let your application's complexity guide your architectural decisions.

The key takeaway is to avoid over-engineering. Use these patterns when they solve real problems you're facing, not because they seem sophisticated. A small API with 3 or 4 endpoints doesn't need the same architecture as a system managing dozens of domains. FastAPI's beauty lies in its ability to start simple and evolve as your needs grow.

That said, understanding these patterns early in your FastAPI journey will help you make better decisions when your application does need to scale. Knowing when to introduce dependency injection, how to structure your tests, and when to create custom exception handlers will save you from painful refactoring later.

If you're building something small, focus on getting it working with clean, readable code. As your application grows and patterns emerge, gradually introduce the practices that make sense for your context. FastAPI gives you the flexibility to build both quick prototypes and complex, production-ready systems.

For more advanced topics like database integration with SQLAlchemy, securing your API with Auth0, or deploying to production environments, check out the FastAPI documentation and the other articles in this series. Happy coding!