TL;DR: In this article I'm going to explain the most important pieces of the Java platform and provide a brief explanation of the process responsible for evolving it. First I'm going to introduce the different Java editions—Java ME, Java SE and Java EE—and some important acronyms related to them, like: JDK, JRE, JVM, JSP, JPA, etc. In the end I will provide an overview of the Java Community Process (JCP).

Before starting I would like to especially thank Leonardo Lima—a seasoned member of the JCP program—for reviewing the contents of this article.

Java Editions

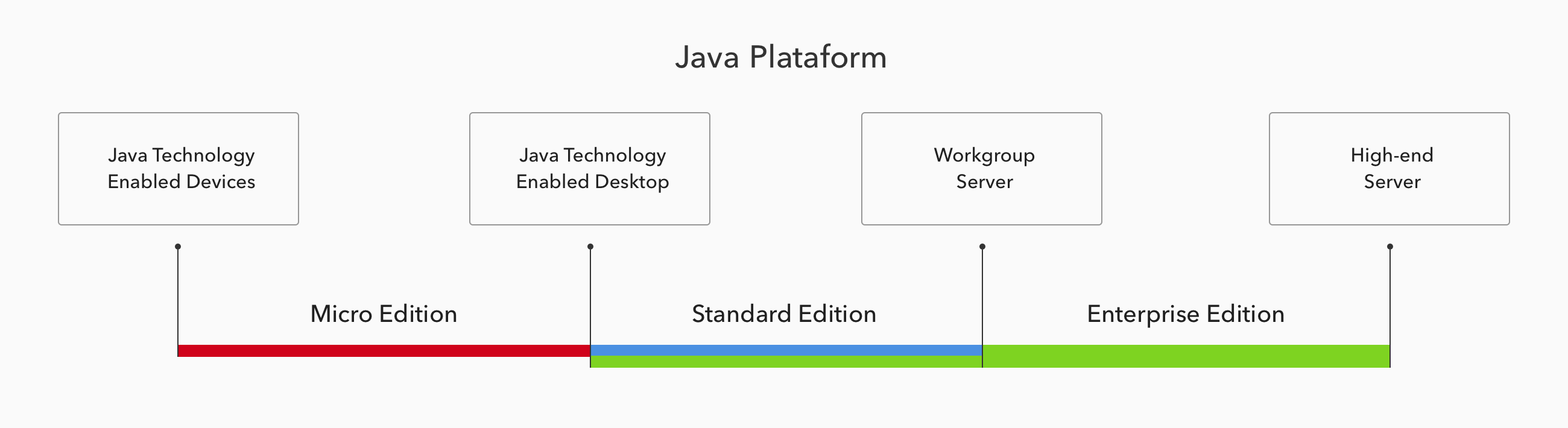

Before diving into the Java Community Process (JCP), it's important to understand the main pieces of the platform. Java is distributed in three different editions: Java Standard Edition (Java SE), Java Enterprise Edition (Java EE) and Java Micro Edition (Java ME).

Java Micro Edition was created to support applications running on mobile and on embedded devices. This edition is not, by far, as popular as its siblings—although lately this technology is finding a new hope in the Internet of Things devices—and will not be the focus of this article, despite the fact that it shares many of the acronyms and processes in its evolution.

Java Standard Edition and Java Enterprise Edition are heavily used worldwide. Together, they are used in various kinds of solutions like web applications, applications servers, big data technologies and so on.

Both editions are composed of a large number of modules and it wouldn't be possible to provide a thorough explanation of the whole platform. Therefore, I'm going to briefly address its most important pieces.

Java Standard Edition (Java SE)

The Java Standard Edition (Java SE) is the minimum requirement to run a Java application. This edition provides a solid basis to the Java Enterprise Edition, and as such I will start by defining some of its components:

- Java Virtual Machine (JVM)

- Java Class Library (JCL)

- Java Runtime Environment (JRE)

- Java Development Kit (JDK)

Java Virtual Machine (JVM)

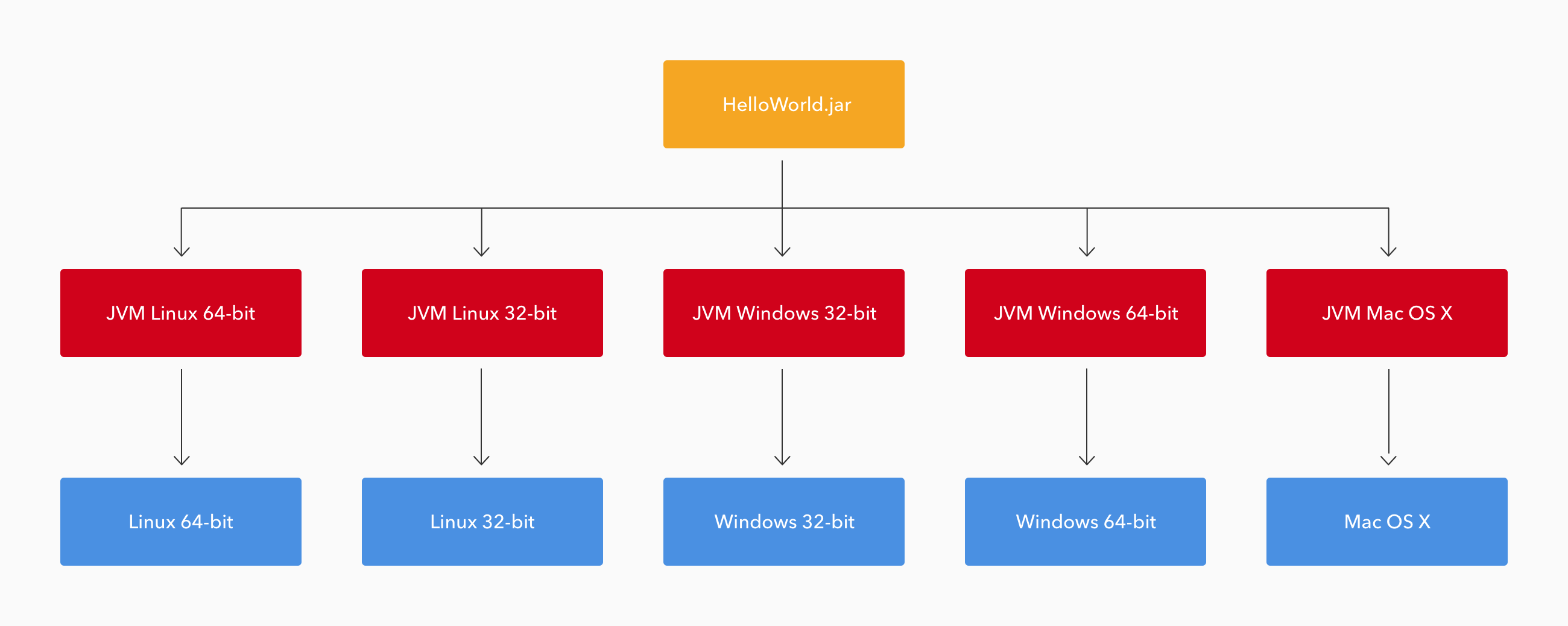

The Java Virtual Machine (JVM) is responsible for supporting the execution of Java applications. This is the piece of the platform that makes the statement write once, run everywhere true for Java. Each particular host operating system (Windows, Linux, Mac OS, etc) needs its own implementation of the JVM, otherwise it wouldn't be possible to run Java applications.

Let's take as an example an arbitrary application that needs to read files from the hosting system. If this application didn't run on an engine like the JVM, that abstracts tasks like IO operations, it would be necessary to write a different program to every single system targeted. This would make the release process slower and it would become harder to support and share this application.

One important concept to bare in mind is that the JVM is, before everything, a specification. Being a specification allows different vendors to create their own implementation of the JVM. Wikipedia has an up to date article that lists open source and proprietary JVMs, but the most important and used ones are: Open JDK (which is open source), J9 from IBM and Oracle JVM (both proprietary).

Java Class Library (JCL)

The Java Class Library is a set of standard libraries that is available to any application running on the JVM. This set of libraries is composed of classes that allow programs to handle commons tasks like: network communication, collection manipulation, file operations, user interface creation, etc. This standard library is also known as the Java Standard Edition API.

As of version 8 of Java, there were more than 4 thousand classes available to the applications running on the JVM. This makes a typical installation of Java consume a large size on disk.

Java members, realizing that Java platform was getting too big addressed the issue by introducing a feature called compact profiles on Java 8 and by making the whole API modular on Java 9.

Java Runtime Environment (JRE)

The Java Runtime Environment (JRE) is a set of tools that provide an environment where Java applications can run effectively. Whenever a user wants to run a Java program, they must choose a vendor and install one of the versions available for their specific environment architecture (Linux x86, Linux x64, Mac OS X, Windows x64, etc). Installing it gives them access to a set of files and programs.

Java has always been extremely careful with backward compatibility. Therefore, installing the latest version available is advised and will probably lead to better performance.

There are two files that are worth noting on a typical JRE installation. The first one is the java executable file. This file is responsible for bootstrapping the JVM that will run the application. The second one is the rt.jar file. This file contains all the runtime classes that comprises the JCL.

Java Development Kit (JDK)

The Java Development Kit (JDK) is an extension of the JRE. Alongside with the files and tools provided by the JRE, the JDK includes compilers and tools (like JavaDoc, and Java Debugger) to create Java programs. For this reason, whenever one wants to develop a Java application, they need to install a JDK.

Nowadays, tools distributed by the JDK, that focus on compiling and basic source code debugging, are often not directly used by developers. Usually Java developers rely on third party tools (like Apache Maven or Gradle) to automate compile, build, and distribution processes. And they also rely on their IDEs (Integrated Development Environments) to build and debug projects on a development environment.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that there are very important tools that help developers on finding and solving bugs, in production and on development stages, that are available on the JDK. JVisualVM is one of these tools. Developers use it to visually monitor, troubleshoot, and profile Java applications.

Java Enterprise Edition (Java EE)

The Java Enterprise Edition (Java EE) was created to extend the Java SE by adding a set of specifications that define capabilities commonly used by enterprise applications. The latest version of this edition contains over 40 specifications that help developers to create applications that communicate through web services, convert object-oriented data to entity relationship model, handle transactional conversations and so on.

One great advantage of having an enterprise edition defined as specifications, is that different vendors can develop their own application servers to support it. This leads to a richer environment where companies can choose the best vendor to support their operations (i.e. they avoid vendor lock-in), and allows open-source and commercial versions of these specifications to be developed and used in a highly compatible way.

Java Enterprise Edition Vendors

At the time of writing there are 8 different vendors that certified their Java EE implementation. Among these vendors, two of them are free and open-source: GlassFish Server Open Source Edition and WildFly.

Oracle, the creator of GlassFish, and Red Hat, the creator of WildFly, also provide proprietary and paid versions of these application servers. Oracle WebLogic Server is the version supported by Oracle and JBoss Enterprise Application Platform is the version supported by Red Hat.

One may wonder why companies like Oracle and Red Hat make available two versions of their applications servers: one open-source and free and the other paid and proprietary. The biggest differences between these versions are that the paid ones usually have more performance and better support. Vendors invest a lot to make these versions run smoothly and to solve any issues that might occur as fast as possible.

Java Enterprise Edition Features

As already stated, Java EE comes with a lot (more than 40) features based on JSRs. These features help companies to handle common needs like persistence, security, web interfaces, state validation and so on. The following list enumerates some of the most important and used features of Java EE:

- Java Persistence API (JPA)—a specification for accessing, persisting and managing data between Java objects and a relational database

- JavaServer Faces (JSF)—a specification for building component-based user interfaces for web applications

- JavaServer Pages (JSP)—a technology that helps software developers create dynamically generated web pages based on HTML

- Java API for RESTful Web Services (JAX-RS)—a spec that provides support in creating RESTful web services

- Enterprise Java Beans (EJB)—a specification for developing components that encapsulates business logic of an application

- Context and Dependency Inject (CDI)—a technology that allows developers to apply inversion of control on Java applications

Java Community Process (JCP)

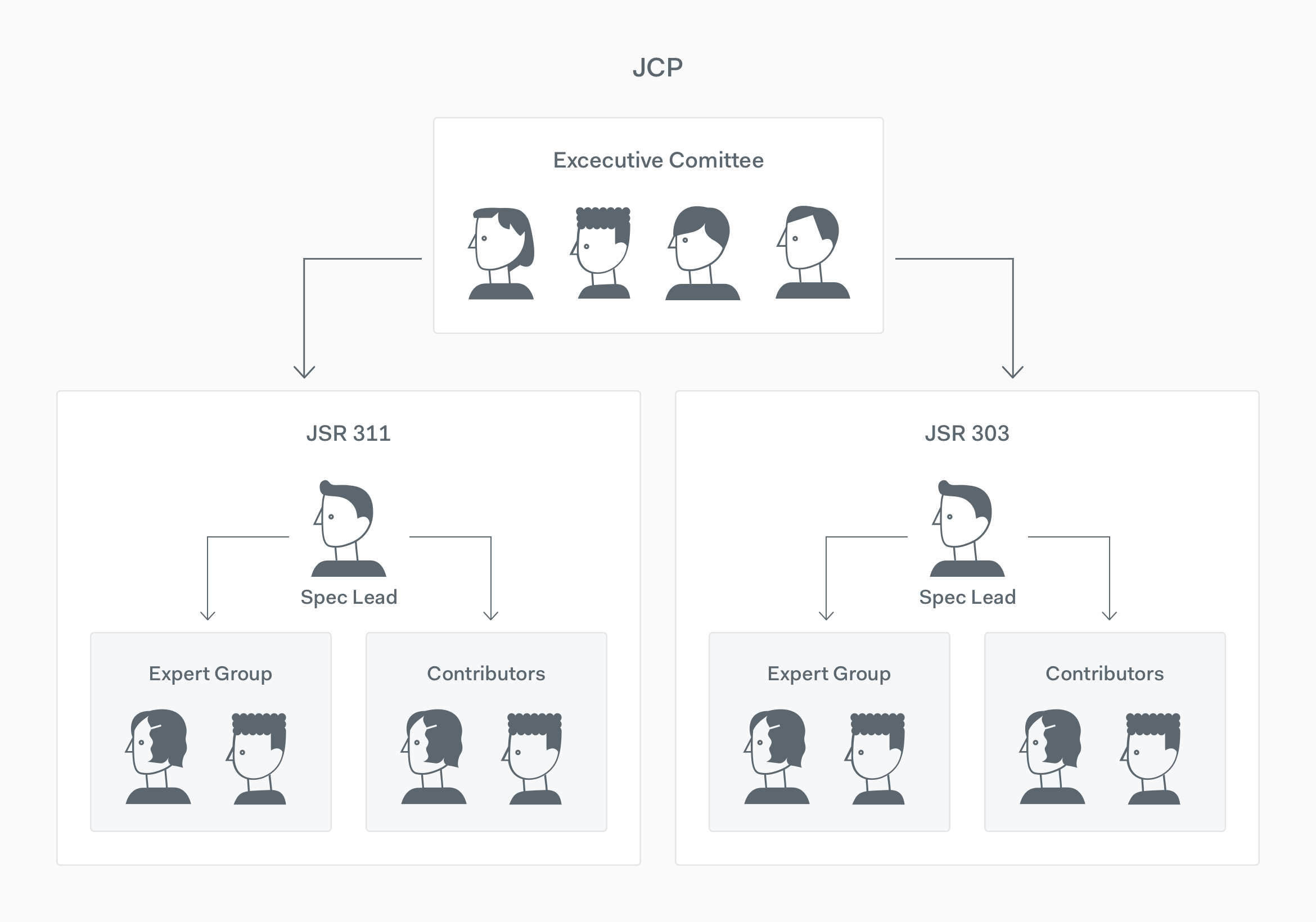

The Java Community Process (JCP) is the process that formalizes and standardizes Java technologies. Interested parties, like developers and companies, cooperate in this process to evolve the platform. Enhancements to any Java technology or introduction of new ones occur through Java Specification Requests (JSRs).

As an example, let's consider the introduction of the Java API for RESTful Web Services (JAX-RS) specification on Java EE. To release this specification in Java EE 5, Sun Microsystems—the company that created filed a JSR to the JCP program, under the number 311. This request defined some details like:

- a description of the proposed specification

- the target platform

- why the need for a new specification

- and technologies that the specification relied on

After submitting this specification request, members of the Executive Committee (EC) analyzed it to decide if the request deserved attention or not. Since it was approved by the EC, Mark Hadley and Paul Sandoz—former employees of Sun Microsystems—were assigned as Specification Leads and kept working on it with the help of Expert Group members and Contributors.

All the different roles and the workflow involved to release any JSR, like the example above, are defined in the JCP program and are governed by the EC.

Java Community Process Membership

To officially participate in any stage of a JSR or process in the JCP, an organization or individual has to sign a Java Specification Participation Agreement (JSPA), a Associate Membership Agreement (AMA) or a Partner Membership Agreement (PMA).

Any entity (human or organization) that signs one of these agreements gets categorized as one of the three types of JCP Membership available: Associate Member, Partner Member or Full Member. Each of these types qualify members to act on different roles in the process. The JCP provides a very detailed explanation of how different kind of subjects (individuals, non-profit organizations or commercial organizations) become members and how they can contribute. But basically, the following rules apply:

- Associate Members can be Contributors to JSRs' Expert Groups, attend JCP Member events and vote in the annual Executive Committee elections for two Associate seats

- Partner Members can serve on the Executive Committee, attend to JCP Member events and vote in the annual Executive Committee elections

- Full Members can work on the Executive Committee, vote in the annual Executive Committee elections, work as Contributors to JSRs and lead these specifications.

Executive Committee (EC)

The Executive Committee (EC) plays a major role in the JCP program. Members of this group have to analyze, comment, vote, and approve on all the JSRs submitted to the program. Besides being responsible for guiding the evolution of the entire platform, the EC and the whole JCP program are also responsible for the JCP program itself, keeping it in adherence to what the community expects from the program and its members.

There are two ways to get elected as a member of this committee: through annual elections; or by being appointed directly by Oracle. Members of the EC are responsible for:

- reviewing and voting to approve or reject new JSR proposals

- reviewing and voting to approve or reject public review drafts

- reviewing and voting to approve or reject final releases

- deciding when JSRs should be withdrawn

- collaborating on revisions to the JCP program

Specification Lead

The Specification Lead is the author of the specification or, like in the example of the JAX-RS spec, someone related to the organization that filed the request. Spec Leads main responsibility is to guide Expert Group members and the Contributors while developing a specification, but they also have to:

- provide the Reference Implementation for the JSR

- complete the Technology Compatibility Kit (TCK)—a suite of tests that checks a particular a JSR for compliance

- update the JSR page on jcp.org, providing documents like Early Draft Review, Public Review, Proposed Final Draft, etc

Contributor

Contributors are Associate Members (i.e. individuals that signed the Associate Membership Agreement) that help the Expert Group and the Specification Lead to test and develop a JSR. This role is the first step to the JCP program. Contributors that provide great help on one or more JSRs have a good chance to be considered as candidates for future Expert Groups and/or to act as a Specification Lead.

Java Specification Requests (JSR)

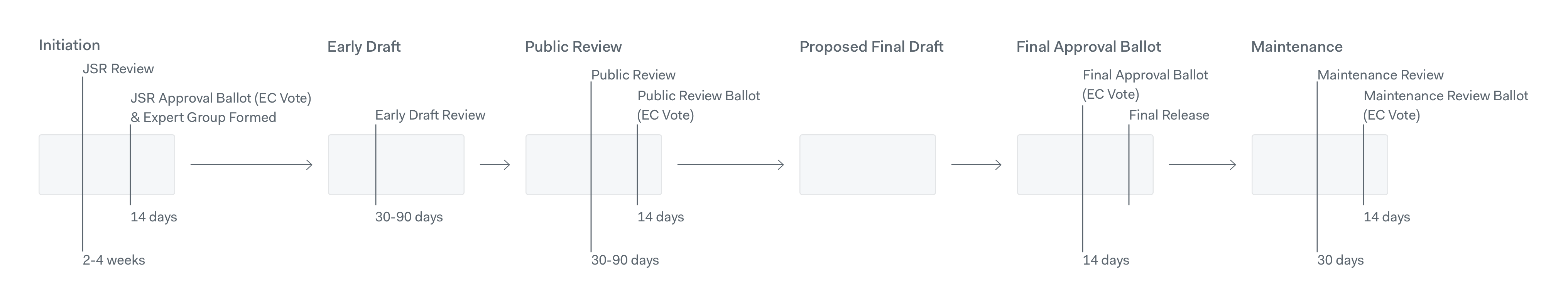

A Java Specification Request is the document that starts an enhancement on the Java platform. Whenever a member of the JCP program sees an opportunity to improve the platform, they create a JSR describing the opportunity and submit it for revision. The JSR then passes through a series of stages until it gets released or discarded. The following list enumerates the stages from the creation of a JSR to its release:

- Write a JSR

- Submit a JSR

- JSR Review

- EG formation

- Early Draft Review

- Public Review

- Proposed Final Draft

- Final Ballot

All these stages are thoroughly defined in the JCP 2.10: Process Document. But below I share a summary of them.

Write a Java Specification Request

The first stage is where an individual or a company that have identified an opportunity writes about it. The artifact expected from this stage must conform to the JSR Submission Template.

Submit a Java Specification Request

After having the template properly filled, the author then submits it to the JCP program. If everything is ok with the submission, then the JSR enters the review phase.

Java Specification Request Review

When a JSR reaches this stage, the EC, and the whole community, have 2 to 4 weeks to analyze and comment on it.

The length of this period is defined by the JSR submitter. This stage ends in a JSR Approval Ballot (JAB), where members of the EC have another 2 weeks to vote on it. To be approved, a JSR has to:

- receive at least 5 votes

- receive yes as the majority of the votes casted (absent votes are ignored)

Expert Group formation

When a JSR gets approved by the EC, the Specification Leads start forming an Expert Group and a team of Contributors to work on the specification. After having the whole crew defined, they start working on the Early Draft Review (EDR).

Early Draft Review

The goal of Early Draft Review is to get the draft specification into a form suitable for Public Review as quickly as possible. The public participation reviewing this draft is desired and important as they can raise architectural and technological issues that can improve the specification.

Public Review

This stage is reached when a JSR is really close to its full definition and the EG is ready to start developing the Reference Implementation (RI). The goal of this stage is to collect some last feedbacks and to give the chance to the community to contribute one last time before moving to the Proposed Final Draft.

Proposed Final Draft

If the Public Review is successful, the Expert Group then prepares the Proposed Final Draft of the specification by completing any revisions necessary to respond to comments. During this phase the JSR gets finished both as a specification and as an implementation (a Reference Implementation). Also, the Specification Lead and the Expert Group is responsible for completing the TCK.

Final Ballot

After having all the documents, the implementation and the TCK finished, the Specification Leads send the Final Draft of the Specification to the JCP program to have the Final Approval Ballot initiated. In case of a successful ballot, after a maximum of 14 days the specification gets published in the JCP website with its RI. The JSR then gets in a Maintenance mode where small updates to it might occur.

Conclusion

As you can see, the Java community has an addiction for acronyms, mainly those that contains the letter J. But alongside with this "addiction", the community has also built an amazing environment, with crystal-clear rules, that enable Java to evolve as a platform and as a community.

The whole process defined as JCP enables multiple companies to rely on technologies that adhere to specifications. Relying on these specifications guarantee that companies will have more than one vendor capable of supporting their operations. As such, if a vendor starts providing bad services or goes bankrupt, the companies have the guarantee that moving to another vendor won't cause too much trouble.

Of course, this process and these specifications don't come for free. Actually the price is quite high, which is the timeframe that new technologies and trends take to get adopted by the JCP community. As Leonardo Lima, a seasoned member of the JCP, put it:

This is why we say that the JCP is a place for standardization, and not innovation. Java innovation occurs outside of the JCP, in communities like Apache and Eclipse. Such innovations eventually become a standard, like Joda Time became JSR310 and Hibernate became JSR338.

As an example, let's say that a company would like to use GraphQL. Right now, there is no specification on any Java edition that supports this technology, and there are chances that Java standards will never support it at all. So, if the company really wants to use it, it will have to take its chances by adopting a solution that wasn't developed based on a Java standard, and therefore will probably suffer from vendor lock-in. This would make the company lose the upside of the specifications.

What about you, what do you think about the Java platform, the JCP program and the whole Java community? Do you think they are moving in the right direction? Would you suggest some changes to it? We would love to hear your ideas.

Aside: Securing Java Applications with Auth0

Auth0 makes it easy for developers to implement even the most complex identity solutions for their web, mobile, and internal applications. Need proof? Check out how easy it is to secure a RESTful Spring Boot application with Auth0.

Auth0 provides the simplest and easiest to use user interface tools to help administrators manage user identities including password resets, creating and provisioning, blocking and deleting users.

For starters, we would need to include a couple of dependencies. Let's say that we are using the Apache Maven build manager. In that case, we would open our pom.xml file and add the following dependencies:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <project xmlns="http://maven.apache.org/POM/4.0.0" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xsi:schemaLocation="http://maven.apache.org/POM/4.0.0 http://maven.apache.org/xsd/maven-4.0.0.xsd"> <!--project definitions ...--> <dependencies> <!--other dependencies ...--> <dependency> <groupId>com.auth0</groupId> <artifactId>auth0</artifactId> <version>1.0.0</version> </dependency> <dependency> <groupId>com.auth0</groupId> <artifactId>auth0-spring-security-api</artifactId> <version>1.0.0-rc.2</version> </dependency> </dependencies> </project>

After that we would simply create, or update, our WebSecurityConfigurerAdapter extension, as shown in the following code excerpt:

package com.auth0.samples; import com.auth0.spring.security.api.JwtWebSecurityConfigurer; import org.springframework.beans.factory.annotation.Value; import org.springframework.context.annotation.Configuration; import org.springframework.security.config.annotation.web.builders.HttpSecurity; import org.springframework.security.config.annotation.web.configuration.EnableWebSecurity; import org.springframework.security.config.annotation.web.configuration.WebSecurityConfigurerAdapter; @Configuration @EnableWebSecurity public class WebSecurityConfig extends WebSecurityConfigurerAdapter { @Value("${auth0.audience}") private String audience; @Value("${auth0.issuer}") private String issuer; @Value("${auth0.secret}") private String secret; @Override protected void configure(HttpSecurity http) throws Exception { http.authorizeRequests() .antMatchers("/").permitAll() .antMatchers("/api/**").authenticated(); JwtWebSecurityConfigurer .forHS256(audience, issuer, secret.getBytes()) .configure(http); } }

And then configure three parameters in the Auth0 SDK, which is done by adding the following properties in the application.properties file:

# change this with your own Auth0 client id auth0.audience=LtiwyfY1Y2ANJerCNTIbT7vVsX5zKBS5 # change this with your own Auth0 client secret auth0.secret=TjpxsT2pMt9Jj6Np45GSPnTnHY-Y-LFyv6fUGGH_EGQLD4_ONBuymn3zxfcCnpdJ # change this with your own Auth0 domain auth0.issuer=https://bkrebs.auth0.com/

Making these small changes would give us a high level of security alongside with a very extensible authentication solution. With Auth0, we could easily integrate our authentication mechanism with different social identity providers—like Facebook, Google, Twitter, GitHub, etc—and also with enterprise solutions like Active Directory and SAML. Besides that, adding Multifactor Authentication to the application would become a piece of cake.

Want more? Take a look at Auth0's solutions and at an article that thoroughly describes how to secure a Spring Application with JWTs.

Auth0 offers a generous free tier to get started with modern authentication.

About the author

Bruno Krebs

R&D Content Architect (Auth0 Alumni)